Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: August 31–September 1, marked by struggles to treat A-bomb disease

Aug. 31, 2024

“To comfort those suffering”

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

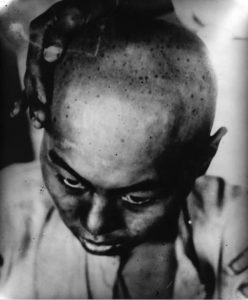

On August 31, 1945, a 22-year-old male soldier significantly suffering from radiation effects due to the atomic bombing died at the Ujina Branch of the Hiroshima First Army Hospital in Hiroshima’s Ujina-machi (in the city’s present-day Minami Ward). Detailed medical records and photographs of the patient’s symptoms have been preserved as a result of a survey led by Masao Tsuzuki, a specialist in radiation medicine, along with colleagues at Tokyo Imperial University (present-day University of Tokyo).

Extremely weakened immune system

On August 6, the soldier was struck by the A-bomb blast on a levee located around 800 meters from the hypocenter and blown into a river. He suffered injuries to his head and back, was hospitalized, and underwent treatment there until August 20.

He returned to his unit for a time, but developed a fever and was hospitalized at the hospital’s Ujina Branch on August 28. Subcutaneous hemorrhagic spotting was observed over his entire body, most notably on his head, from which his hair had fallen out. He also developed anemia and bleeding mouth ulcers. He lost consciousness on August 30 and died on the morning of August 31.

A normal white blood cell count is typically between 4,000 and 9,000 per cubic millimeter of blood, but the patient’s number had fallen below 100 just prior to his death. His immune system was extremely weakened.

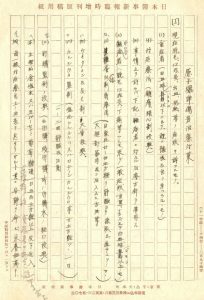

Around 500 people were hospitalized at the Ujina Branch, and Mr. Tsuzuki wrote in a personal account in the journal Seitai (in English, ‘Ecology’), published in 1953, “This was our first experience of any disaster from an atomic bomb, and we had no idea about the prognosis or treatments and so on.” On September 1, he gathered people engaged in the work at the Ujina Branch to exchange ideas about the situation, based on which was put together the immediate “Measures for treating A-bomb casualties.”

Among A-bomb survivors who showed symptoms of bleeding or hair loss, those who were considered difficult to treat and had “a white blood cell count below 1,000 and thought to have a poor prognosis” were classified as being in serious condition, with treatment of symptoms, including pain relief, considered fundamental for these patients. On the other hand, those with a white blood cell count exceeding 1,000 were considered to be in moderately-severe condition. Mr. Tsuzuki called for treatments such as intramuscular injections of small amounts of a patient’s venous blood into thigh muscle in an attempt to restore the blood-production function of bone marrow as well as administration of large doses of vitamins, among other methods.

Mr. Tsuzuki wrote in his personal account, “I wasn’t entirely convinced, but I couldn’t stand by and watch the extremely tense situation there any longer. I intended to comfort those suffering in any way I could, even emotionally.” He also showed the need for those who had been within two kilometers of the hypocenter at the time of the A-bomb’s detonation and experienced such symptoms as vomiting or diarrhea to seek medical attention even if symptoms had subsided.

These painstaking treatment methods amidst a shortage of medical supplies and equipment were communicated to those in the medical community through a lecture by Mr. Tsuzuki held in Hiroshima on September 3, among other means. Ken Takeuchi, director of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, wrote about details of the lecture in a pocket notebook.

Local physicians also worked hard

On the other hand, local physicians were also working hard independently. On August 26, Michihiko Hachiya, director of the Hiroshima Teishin Hospital, wrote “Warnings about A-bomb disease” and posted the document to relevant parties, informing them of decreased white blood cell counts and other symptoms. On August 29, Professor Chuta Tamagawa, a pathologist at Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School (present-day Hiroshima University School of Medicine), set about conducting pathological autopsies next to the hospital. He set up an autopsy table in a shack and started his work.

In his book Hiroshima Diary, published in 1955, Dr. Hachiya wrote that when he listened to the lecture by Mr. Tsuzuki and other medical experts from Tokyo on September 3, he felt that it would serve as “good reference,” but at the same time, with a sense of rivalry he thought, “I mustn’t let my guard down.” Hiroshima’s physicians were also facing head-on the unknown damage caused by the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on August 31, 2024)