Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: September 13, child returns home, confronts older brother’s death

Sep. 13, 2024

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On September 13, 1945, Kimio Inoue, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who was nine years old at the time and a fourth-grader at Oko National School (present-day Oko Elementary School, in the city’s Minami Ward) was at Hiroshima Station for the first time in about five months. Starting in April that year, around 250 schoolchildren from the school had been gradually evacuated in groups to the village of Honda (in present-day Shobara City), in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. On this day, they returned and held a farewell ceremony in front of the station as the students who were returning to Hiroshima disbanded.

Mr. Inoue said, “Ninoshima Island was visible right there.” Many buildings that had blocked sight of the island, located around 10 kilometers to the southwest, were burned to the ground. When he returned to his home in the area of Midori-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), Isao, his older brother by three years, was as he expected nowhere to be found.

On August 6, Isao, a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Middle School (present-day Motomachi High School), had been mobilized to engage in the work of building demolition to create fire lanes in the downtown area of the city. He had suffered severe burns to his upper body and fled into the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where he informed someone around him of his name and address.

On August 7, when the family went to the hospital after hearing the news from the same individual, Isao had already died. Mr. Inoue said, “The burns on his face were so severe that even our family couldn’t tell it was him. I heard my mother had recognized Isao by the shape of his toenails. She used to cut his toenails when he was little.”

Mr. Inoue first learned of Isao’s death from a postcard that was delivered to the place where he had been evacuated. Before Isao entered middle school, they would go to the national school together and swim in the sea. “I didn’t want to cry in front of everyone,” said Mr. Inoue, describing his feelings at the time he heard the news. After he got into bed at night, he shed tears alone.

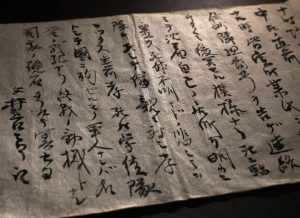

Now serving as director of the group “Meeting of victims such as mobilization students in Hiroshima,” Mr. Inoue continues to do the work each month of cleaning the Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students, located to the south of the A-Bomb Dome. Last month, he donated a condolence book filled with messages of sympathy following his older brother’s death to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. A message from his late father, Shiro, in remembrance of Isao is included in the book. “He showed loyalty toward his parents even in death,” he wrote, because the act of telling people surrounding him his name and address ensured his body could be returned to his family.

When the war ended, the disbanding of the collective evacuation of third- to sixth-graders from national schools was expedited. The families of many of the students had been killed in the bombing.

(Originally published on September 13, 2024)

On September 13, 1945, Kimio Inoue, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who was nine years old at the time and a fourth-grader at Oko National School (present-day Oko Elementary School, in the city’s Minami Ward) was at Hiroshima Station for the first time in about five months. Starting in April that year, around 250 schoolchildren from the school had been gradually evacuated in groups to the village of Honda (in present-day Shobara City), in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. On this day, they returned and held a farewell ceremony in front of the station as the students who were returning to Hiroshima disbanded.

Mr. Inoue said, “Ninoshima Island was visible right there.” Many buildings that had blocked sight of the island, located around 10 kilometers to the southwest, were burned to the ground. When he returned to his home in the area of Midori-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), Isao, his older brother by three years, was as he expected nowhere to be found.

On August 6, Isao, a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Middle School (present-day Motomachi High School), had been mobilized to engage in the work of building demolition to create fire lanes in the downtown area of the city. He had suffered severe burns to his upper body and fled into the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where he informed someone around him of his name and address.

On August 7, when the family went to the hospital after hearing the news from the same individual, Isao had already died. Mr. Inoue said, “The burns on his face were so severe that even our family couldn’t tell it was him. I heard my mother had recognized Isao by the shape of his toenails. She used to cut his toenails when he was little.”

Mr. Inoue first learned of Isao’s death from a postcard that was delivered to the place where he had been evacuated. Before Isao entered middle school, they would go to the national school together and swim in the sea. “I didn’t want to cry in front of everyone,” said Mr. Inoue, describing his feelings at the time he heard the news. After he got into bed at night, he shed tears alone.

Now serving as director of the group “Meeting of victims such as mobilization students in Hiroshima,” Mr. Inoue continues to do the work each month of cleaning the Memorial Tower to the Mobilized Students, located to the south of the A-Bomb Dome. Last month, he donated a condolence book filled with messages of sympathy following his older brother’s death to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. A message from his late father, Shiro, in remembrance of Isao is included in the book. “He showed loyalty toward his parents even in death,” he wrote, because the act of telling people surrounding him his name and address ensured his body could be returned to his family.

When the war ended, the disbanding of the collective evacuation of third- to sixth-graders from national schools was expedited. The families of many of the students had been killed in the bombing.

(Originally published on September 13, 2024)