Hidankyo awarded Nobel Peace Prize: Hisaharu Matsui, former teacher colleague of Sunao Tsuboi, serves as guide to carry on Tsuboi’s wish for “nuclear abolition”

Oct. 24, 2024

Matsui communicates Tsuboi’s spirit to next generation three years after his death

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

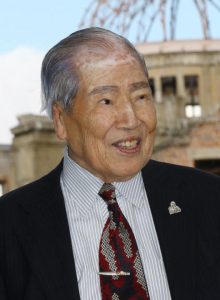

October 24 marked three years since the death of Sunao Tsuboi at the age of 96. Mr. Tsuboi served as co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), the group announced as being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He also worked as chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations. Hisaharu Matsui, 70, a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward and a former junior colleague of Mr. Tsuboi when they worked as teachers, is one of those who have taken up the baton for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Mr. Matsui works as a guide at Peace Memorial Park, in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, communicating to children Mr. Tsuboi’s experiences in the atomic bombing and his wishes for peace in the hope of having “Mr. Tsuboi continue to live on in everyone.”

On October 20, Mr. Matsui guided 17 high school students visiting from Gunma Prefecture around Peace Park. While touring the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and the A-bomb Dome, he introduced them to the story of Mr. Tsuboi. He mentioned how Mr. Tsuboi had experienced the atomic bombing and suffered burns over nearly his entire body, and how he had fled to an area near the west end of Miyuki Bridge (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), where he had written “Tsuboi died here” on the ground using a small stone. Mr. Matsui added, “He said repeatedly that nuclear weapons must be eliminated from the world.”

Mr. Matsui taught mathematics. In 1976, he first met Mr. Tsuboi, who served at the time as vice principal of Midorimachi Junior High School (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), Mr. Matsui’s first school as a teacher. In Hiroshima, where peace education is actively promoted, Mr. Tsuboi had earned the nickname “Mr. Pikadon” (a combination of words in Japanese that mean the flash [“pika”] and boom [“don”] of the bombing) because he spoke of his experiences in the atomic bombing to his students. In contrast, Mr. Matsui, a second-generation A-bomb survivor, was unsure of what he could do.

One day, when Mr. Matsui was working overtime late at night, he confided in Mr. Tsuboi that, because he was a math teacher, “I don’t feel confident teaching peace education.” He described how Mr. Tsuboi had encouraged him by replying, “I teach math, too. Don’t only talk about the atomic bombing; also teach them about the importance of life.”

Together with Mr. Tsuboi, he worked to trace the dates, times, and locations of the deaths in the atomic bombing of students and teachers from the Hiroshima Municipal Third National School, Midorimachi Junior High School’s predecessor. Together with students, they would visit the families of A-bomb victims, work that led to publication of a booklet titled “Blank School Register” in 1980. The booklet is still being used as supplementary reading material in peace-education programs.

Mr. Tsuboi, after fleeing to the west end of Miyuki Bridge, lost consciousness and was taken to Ninoshima Island (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), where he was, as chance would have it, reunited with his mother. Mr. Matsui surmised that Mr. Tsuboi’s desire to fill in the “blanks” caused by the atomic bombing stemmed from the idea that, “He himself could have died without anyone knowing and, in that way, become a blank himself.”

With the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize, Mr. Tsuboi’s life has found its way back into the spotlight. Mr. Matsui vowed, “Nuclear weapons won’t be eliminated because of the prize. I’ll continue to speak about Mr. Tsuboi as long as I live.” With his senior colleague’s motto “Never give up” in mind, he works to pass on such ideas to future generations.

(Originally published on October 24, 2024)