Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shimbun and the press code — Series epilogue, Part 1: Fear of censorship inhibited media

Sep. 10, 2024

by Kazuo Yabui, Appointed Senior Staff Writer

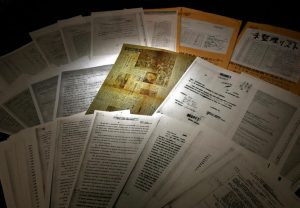

The Chugoku Shimbun feature article series titled “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shimbun and the press code” has been carried in the newspaper in three parts from September of last year through this month. For the series, we examined nearly 30,000 documents that had undergone censorship review by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) during Japan’s occupation period, reporting on the reality of censorship. How did the censorship affect media reports involving the atomic bombings? What is the lesson we in the modern era need to take from that history? In wrapping up this series, we will provide a summary and offer proposals.

In September 1945, the GHQ announced a press code for the Japanese media. When we looked into how many articles published by the Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima, an evening newspaper issued by an affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun, had been subjected to censorship, we found that only one article for each newspaper had been deemed to violate the press code. The number was far less than our initial expectations at the time we embarked on our full-fledged survey of such articles. Why was that the case?

Of the Chugoku Shimbun’s articles published during that period, censorship was exercised only on a 12-line article that had been published on July 22, 1946. That article reported that the mayor of Hiroshima City had applied for permission from General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, to ask overseas nations for donations to fund the city’s recovery efforts. The article was censored because it contained General MacArthur’s name. In the Yukan Hiroshima, only one article, published on July 6, 1946, was deemed to violate the press code because it had carried for the first time a photograph taken on the day of the atomic bombing.

The aim of censorship was made up of two elements—the promotion of democratization and the control of speech in post-war Japan. Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who specializes in the history of the atomic bombings, said, “The fact that the Chugoku Shimbun had very few articles that violated the press code can be interpreted to mean that the censorship was that effective.” Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus at Waseda University and someone who studies the media during Japan’s occupation period, said, “The GHQ censored the media’s reports while concealing that fact from the Japanese public. Attention should also be paid to their underhanded approach.”

Post-print censorship might have been reason

How did those engaged in the news media during the occupation period interpret the censorship? Testimonies from previous staff of the Chugoku Shimbun are preserved in the company’s history.

In a publication titled Chugoku Shimbun 80-nen Shi (in English, ‘80-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun’), Shigetoshi Itokawa, who then served as managing editor of the editorial department, said, “The censorship was not overt, and nothing was ever specifically mentioned to me.” Reflecting on his past experience, Mr. Itokawa said, “In my personal view, we were maintaining a policy of compliance with the press code based on the idea that we could create a very free and open newspaper.”

In fact, the Chugoku Shimbun declared in its corporate philosophy of 1948 that, “We will strictly adhere to the press code.”

One of the reasons only a few articles were found to be in violation of the press code can be the post-print censorship process applied to many local newspapers, including the Chugoku Shimbun. Compared to the pre-print censorship review conducted for national newspapers, the post-print process made immediate response to the GHQ’s demands impossible, forcing the media to practice self-restraint at a higher level than was necessary.

Kiyoshi Matsue, an editorial writer for the Chugoku Shimbun during the occupation period, previously made comments along those lines. In the notes of a roundtable-style discussion included in the publication Chugoku Shimbun Roso 50-nen Shi (in English, ‘50-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun labor union’), published in 1996, Mr. Matsue was described as pointing out the difference in the censorship conducted before publication and after publication. His explanation was based on his experience of being subjected to pre-print censorship when he appeared on a news commentary program broadcast by NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation).

In the notes, Mr. Matsue said, “When I appeared on the NHK program, the GHQ’s censorship staff came to the broadcast studio and conducted the censorship review in advance. When we tried to report on the news about a labor strike at Toyo Kogyo (present-day Mazda Motor Corporation), the censor told us not to include it, so we had no choice but to bury the story.” He added, “Post-print censorship was the most frightening practice, to be honest … If things went wrong, we would get in hot water later.”

Post-war recovery was main news

News coverage at that time was focused on post-war recovery efforts. With that, the reality was that only a few articles that criticized the atomic bombing were written, leading to only minor coverage of that issue. In addition, the articles describing health effects in A-bomb survivors mainly carried only fragmentary information.

Given the number of articles judged to be in violation of the press code, the effects the censorship had on news coverage involving the atomic bombings are probably impossible to ascertain. The more we tried to pursue the reality of censorship, the more we repeatedly ran into such obstacles as missing materials. We do not know whether the missing materials were scattered and lost, or whether they were intentionally hidden. Such “voids” represent a hindrance preventing both past and future efforts to verify the reality.

Censorship is not allowed by either the U.S. Constitution or Japan’s. That censorship was used as a way to promote democratization in Japan is truly a great contradiction.

In recent years, the term “reading between the lines” is often used to describe the news media’s handling of the government. It appears that the shadow of the media’s “self-restraint” during the occupation period continues to serve as a drag on their activities. Japan’s post-war democracy, which began with such contradictions, is about to mark its 80th anniversary. We must never allow the arrival of another era with widespread censorship.

(Originally published on September 10, 2024)

The Chugoku Shimbun feature article series titled “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Chugoku Shimbun and the press code” has been carried in the newspaper in three parts from September of last year through this month. For the series, we examined nearly 30,000 documents that had undergone censorship review by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) during Japan’s occupation period, reporting on the reality of censorship. How did the censorship affect media reports involving the atomic bombings? What is the lesson we in the modern era need to take from that history? In wrapping up this series, we will provide a summary and offer proposals.

In September 1945, the GHQ announced a press code for the Japanese media. When we looked into how many articles published by the Chugoku Shimbun and the Yukan Hiroshima, an evening newspaper issued by an affiliated company of the Chugoku Shimbun, had been subjected to censorship, we found that only one article for each newspaper had been deemed to violate the press code. The number was far less than our initial expectations at the time we embarked on our full-fledged survey of such articles. Why was that the case?

Of the Chugoku Shimbun’s articles published during that period, censorship was exercised only on a 12-line article that had been published on July 22, 1946. That article reported that the mayor of Hiroshima City had applied for permission from General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, to ask overseas nations for donations to fund the city’s recovery efforts. The article was censored because it contained General MacArthur’s name. In the Yukan Hiroshima, only one article, published on July 6, 1946, was deemed to violate the press code because it had carried for the first time a photograph taken on the day of the atomic bombing.

The aim of censorship was made up of two elements—the promotion of democratization and the control of speech in post-war Japan. Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who specializes in the history of the atomic bombings, said, “The fact that the Chugoku Shimbun had very few articles that violated the press code can be interpreted to mean that the censorship was that effective.” Taketoshi Yamamoto, professor emeritus at Waseda University and someone who studies the media during Japan’s occupation period, said, “The GHQ censored the media’s reports while concealing that fact from the Japanese public. Attention should also be paid to their underhanded approach.”

Post-print censorship might have been reason

How did those engaged in the news media during the occupation period interpret the censorship? Testimonies from previous staff of the Chugoku Shimbun are preserved in the company’s history.

In a publication titled Chugoku Shimbun 80-nen Shi (in English, ‘80-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun’), Shigetoshi Itokawa, who then served as managing editor of the editorial department, said, “The censorship was not overt, and nothing was ever specifically mentioned to me.” Reflecting on his past experience, Mr. Itokawa said, “In my personal view, we were maintaining a policy of compliance with the press code based on the idea that we could create a very free and open newspaper.”

In fact, the Chugoku Shimbun declared in its corporate philosophy of 1948 that, “We will strictly adhere to the press code.”

One of the reasons only a few articles were found to be in violation of the press code can be the post-print censorship process applied to many local newspapers, including the Chugoku Shimbun. Compared to the pre-print censorship review conducted for national newspapers, the post-print process made immediate response to the GHQ’s demands impossible, forcing the media to practice self-restraint at a higher level than was necessary.

Kiyoshi Matsue, an editorial writer for the Chugoku Shimbun during the occupation period, previously made comments along those lines. In the notes of a roundtable-style discussion included in the publication Chugoku Shimbun Roso 50-nen Shi (in English, ‘50-year history of the Chugoku Shimbun labor union’), published in 1996, Mr. Matsue was described as pointing out the difference in the censorship conducted before publication and after publication. His explanation was based on his experience of being subjected to pre-print censorship when he appeared on a news commentary program broadcast by NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation).

In the notes, Mr. Matsue said, “When I appeared on the NHK program, the GHQ’s censorship staff came to the broadcast studio and conducted the censorship review in advance. When we tried to report on the news about a labor strike at Toyo Kogyo (present-day Mazda Motor Corporation), the censor told us not to include it, so we had no choice but to bury the story.” He added, “Post-print censorship was the most frightening practice, to be honest … If things went wrong, we would get in hot water later.”

Post-war recovery was main news

News coverage at that time was focused on post-war recovery efforts. With that, the reality was that only a few articles that criticized the atomic bombing were written, leading to only minor coverage of that issue. In addition, the articles describing health effects in A-bomb survivors mainly carried only fragmentary information.

Given the number of articles judged to be in violation of the press code, the effects the censorship had on news coverage involving the atomic bombings are probably impossible to ascertain. The more we tried to pursue the reality of censorship, the more we repeatedly ran into such obstacles as missing materials. We do not know whether the missing materials were scattered and lost, or whether they were intentionally hidden. Such “voids” represent a hindrance preventing both past and future efforts to verify the reality.

Censorship is not allowed by either the U.S. Constitution or Japan’s. That censorship was used as a way to promote democratization in Japan is truly a great contradiction.

In recent years, the term “reading between the lines” is often used to describe the news media’s handling of the government. It appears that the shadow of the media’s “self-restraint” during the occupation period continues to serve as a drag on their activities. Japan’s post-war democracy, which began with such contradictions, is about to mark its 80th anniversary. We must never allow the arrival of another era with widespread censorship.

(Originally published on September 10, 2024)