Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: October 23, Japanese military report describes health effects in people who entered Hiroshima after bombing

Oct. 23, 2024

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

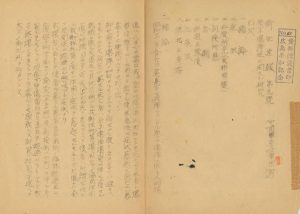

On October 23, 1945, the Medical Department of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Chugoku District Military Headquarters, which had been situated in Hiroshima City during the war, put together what was called the “Health Bulletin No. 9” involving health effects from the atomic bombings. The department primarily focused on the health of soldiers who had been mobilized to work in the city center disposing of victims’ bodies and other tasks immediately after the bombing, and continued to monitor their health conditions after the end of the war.

According to the report, the results from blood testing on 136 cases were analyzed for “those not living in Hiroshima City on the day of the bombing but who engaged in work in the city or stayed there for other activities after August 6.” A decrease in white blood cell count, labeled “leucopenia,” was observed in 89 cases, or 65 percent of the total number.

Of that number of cases, the decrease was significant in people who had entered the city within 500 meters of the hypocenter early on after the atomic bombing. In addition, those who stayed in the city for long periods had “marked effects” from the bombing, stated the report.

The report became the earliest record demonstrating radiation effects in cases of “entrance into the city after the bombing,” a situation that is still not entirely understood. The study conducted at the time had only a limited number of subjects and concluded that “no one studied had died and only a few suffered severe symptoms.” However, the testimonies and personal notes written by A-bomb survivors and the bereaved family members of the victims reveal that countless cases of deaths occurred after people had entered the A-bombed city.

Keiko Morioka, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, who was nine at the time, lost her cousin, Tokiko Tomino, who had entered Hiroshima after the bombing. According to Ms. Morioka, Ms. Tomino was like “a beautiful older sister” who was around ten years older than she was.

Tokiko had been able to avoid the A-bombing disaster on August 6 because she was staying at a relative’s home in Fuchu-cho in the suburbs of Hiroshima. But five or six days after the bombing, she entered the city and went to her family home in the area of Takajo-machi, located in the central part of the city, in search of her missing father. Thereafter, she walked around other areas of the city as she looked for her father, such as the ruins of the theater that he had managed in Hiroshima’s downtown, over a period of around 10 days.

The image of Tokiko becoming ill is seared into the memory of Ms. Morioka, who had been evacuated to the same relative’s home. She said, “When Tokiko returned to the house, she turned pale and fell into bed, saying ‘I feel terrible.’ Both her hair and teeth fell out … .” Tokiko died on September 6.

(Originally published on October 23, 2024)

On October 23, 1945, the Medical Department of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Chugoku District Military Headquarters, which had been situated in Hiroshima City during the war, put together what was called the “Health Bulletin No. 9” involving health effects from the atomic bombings. The department primarily focused on the health of soldiers who had been mobilized to work in the city center disposing of victims’ bodies and other tasks immediately after the bombing, and continued to monitor their health conditions after the end of the war.

According to the report, the results from blood testing on 136 cases were analyzed for “those not living in Hiroshima City on the day of the bombing but who engaged in work in the city or stayed there for other activities after August 6.” A decrease in white blood cell count, labeled “leucopenia,” was observed in 89 cases, or 65 percent of the total number.

Of that number of cases, the decrease was significant in people who had entered the city within 500 meters of the hypocenter early on after the atomic bombing. In addition, those who stayed in the city for long periods had “marked effects” from the bombing, stated the report.

The report became the earliest record demonstrating radiation effects in cases of “entrance into the city after the bombing,” a situation that is still not entirely understood. The study conducted at the time had only a limited number of subjects and concluded that “no one studied had died and only a few suffered severe symptoms.” However, the testimonies and personal notes written by A-bomb survivors and the bereaved family members of the victims reveal that countless cases of deaths occurred after people had entered the A-bombed city.

Keiko Morioka, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, who was nine at the time, lost her cousin, Tokiko Tomino, who had entered Hiroshima after the bombing. According to Ms. Morioka, Ms. Tomino was like “a beautiful older sister” who was around ten years older than she was.

Tokiko had been able to avoid the A-bombing disaster on August 6 because she was staying at a relative’s home in Fuchu-cho in the suburbs of Hiroshima. But five or six days after the bombing, she entered the city and went to her family home in the area of Takajo-machi, located in the central part of the city, in search of her missing father. Thereafter, she walked around other areas of the city as she looked for her father, such as the ruins of the theater that he had managed in Hiroshima’s downtown, over a period of around 10 days.

The image of Tokiko becoming ill is seared into the memory of Ms. Morioka, who had been evacuated to the same relative’s home. She said, “When Tokiko returned to the house, she turned pale and fell into bed, saying ‘I feel terrible.’ Both her hair and teeth fell out … .” Tokiko died on September 6.

(Originally published on October 23, 2024)