Hidankyo awarded Nobel Peace Prize: Ms. Kimura, a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing who, with her father’s unfulfilled hopes, calls for nuclear abolition, attends the award ceremony

Dec. 10, 2024

Nobel Peace Prize will be the “last tailwind”

by Fumiyasu Miyano, Staff Writer

Oslo-Hisako Kimura, an 87-year-old survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima who now lives in Sendai City, will attend the award ceremony of the Nobel Peace Prize to the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) on December 10 in Oslo, Norway. With the unfulfilled hopes of her father, whose life was taken by the atomic bomb, etched in her mind, she has been campaigning for a world free of nuclear weapons and war, so no one else will have to face the same kind of “suffering and regret” she did.

Ms. Kimura arrived in Oslo on the night of December 8 as a member of a delegation sent by the Nihon Hidankyo. She plans to stay in Oslo until December 12, and to give her A-bomb testimony while in the city. “I want to appeal to my heart’s content,” she said enthusiastically.

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Kimura, then eight years old and in the second grade at Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), was exposed to the atomic bombing at a house owned by her grandfather in the city’s Osuga district (now part of Minami Ward), 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. She had no major injuries, but her grandfather, who was outside the house, was groaning with his skin peeled off.

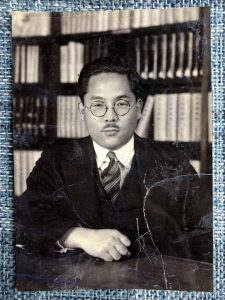

Sadaomi Yamagata, then 42, Ms. Kimura’s father and a physician, was severely burned near their home in the Horikawa district (now part of Naka Ward), about 700 meters from the hypocenter. When her mother found him three days later in a suburban hospital, his face was red and swollen. He died that night, leaving behind the words: “I am so mortified.” “How hot it must have been.” She still cries when she talks about her father.

Her grandfather also died six days later. When he was still alive, she wished he would soon go to the other world because his injured body was infested with maggots and smelled terrible. She regrets she wished this.

The life of the well-to-do family had changed completely. Her mother, who had never worked before, carried cosmetics on her back and sold them on the islands of the Seto Inland Sea to feed her four children. With the sole reason of letting her mother rest, she cooked, washed, and cleaned by herself. “I did the housework after I came home from school. I felt like I was no longer a child.”

She hated the United States, which had dropped the atomic bomb. She did not feel like begging U.S. soldiers for chocolate, so she stayed away from them. When she was in distress, she visited her father’s grave and talked to him with tears. She felt as if he said, “I understand your pain.”

The family moved to Tokyo when her brothers got into schools there, where Ms. Kimura and her mother joined the campaign by the Hidankyo. Then, she got married and moved to Sendai City. Thinking that she did not want her children to go through the same hardship she had, she assumed the position of secretary general of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association in Miyagi Prefecture around 1990. She participated in demonstrations for national compensation for A-bomb damages, and fought in the class action lawsuit over A-bomb disease certification.

Since 2005, she has visited the United States three times in conjunction with the Review Conferences of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). It all started with a meeting with American students who thanked Ms. Kimura for sharing her A-bomb experience. She thought: “There are some people who would listen to me. Instead of hating them, I should try to persuade them.” Still, she poured out her feelings at the gathering in New York in 2010: “I want to see my father. Give back my father.”

As secretary general, she continues to hold the memorial service for the victims and the A-bomb exhibit every summer with the help of second-generation A-bomb survivors and citizen groups. She feels the award to the Nihon Hidankyo is the “last tailwind.” Ms. Kimura says: “We want to use the award as an opportunity to work with people around the world. If we could not, the world would end.”

(Originally published on December 10, 2024)