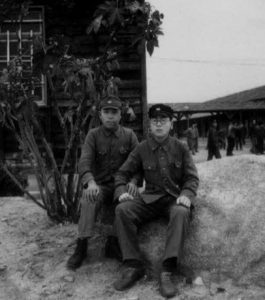

My Life — Interview with Hiromu Morishita (1930–), A-bomb survivor and teacher, Part 6: Days of recuperation

Apr. 26, 2022

Physical and psychological scars remained even after return to school

When the day of the atomic bombing turned to night, Hiromu Morishita was carried to an acquaintance’s house in the area of Kawauchi, in Hiroshima’s Asaminami Ward.

They apparently discovered me exhausted and collapsed in a field. I had a high fever and was mumbling incoherently. It was my father who finally found me.

At the time, my father was a teacher at the Hiroshima Municipal Shipbuilding Engineering School (present-day Hiroshima Municipal Commercial High School). On August 6, he is said to have led his students to a temple in the area of Koi (now part of the city’s Nishi Ward). The older of my two younger sisters who had been mobilized for work in a military footwear factory in the Misasa district (in present-day Nishi Ward), and my youngest sister, who had been evacuated to the area of Imuro (now part of Asakita Ward), were both safe. Only my mother, who was home at the time, was killed in the atomic bombing. She was 40 years old. A few days later, my father collected her bones and brought them back with him. I didn’t even cry, though, probably because my emotions had been numbed. It took some time before sadness hit me.

I continued to recuperate at my acquaintance’s home for a while. Because bloody pus was seeping from my face and limbs, I had no choice but to just lie on my back. When I heard that dead bodies were being cremated on the riverbank, I was worried I would be next. After paying me a visit, my aunt, who had no visible injuries from her experience in the bombing, apparently threw up black bubbles from her mouth and died. That is the horror of radiation. My father tried everything he had learned about how to treat my wounds. He would knead powder obtained from burned paulownia with oil and apply the concoction to my wounds and skin as well as light moxa on my body.

I felt neither regret nor anger when I learned that the war had ended. I was relieved, because I was not in any position to run and escape into air-raid shelters with everyone else if an air-raid alert had sounded. All I could do was lie in bed with a futon cover over my head.

Even after my wounds finally healed, no one would let me look at myself in the mirror. I underwent keloid scar surgery once the following spring and once in the summer at Hiroshima Teishin Hospital (in the city’s Naka Ward). However, scar contractures were left on the skin from my face to my neck, and most of my left ear shrunk and disappeared. Naturally, it was hard for me. Children would stare at me. I couldn’t say to them, “Stop looking at me.”

He returned to school the next spring, in 1946.

I spent that winter at my relative’s house in the area of Kitahiroshima-cho. The following spring, my classmates gathered at a branch Army hospital in the Eba area (now part of Naka Ward). Normally, we would have rejoiced together about the fact that we had survived. But I was not up for that and only wanted to scream like a madman. During the war, I was able to withstand anything for the sake of the emperor. However, when Japan lost the war, the emperor became an ordinary person. We had lost our spiritual backbone.

(Originally published on April 26, 2022)