Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: In November, mixed feelings of sweetness, hatred in children

Nov. 14, 2024

by Maho Yamamoto, Staff Writer

In November 1945, members of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey team, a joint group made up of the U.S. Army and Navy, was investigating the status of devastation in Hiroshima City. Established the previous year, in 1944, by U.S. presidential executive order to analyze air raids that had been carried out on Germany, the team set about studying the “effectiveness” of the atomic bombings of Japan, among other aims. Around 30 members of a physical damage survey unit of the team began investigating the city area on October 14, work that lasted until November 26.

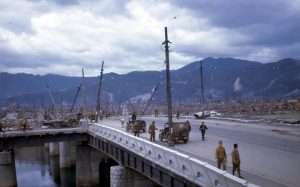

Among many photographs taken of destroyed buildings and bridges, some not directly related to the survey remain today. One taken on Aioi Bridge (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) near the hypocenter by H. J. Peterson, a member of the Navy’s photography unit, shows children receiving sweets from U.S. military personnel.

The process of stationing Allied Forces in Hiroshima Prefecture began in earnest on October 6. By the next day, October 7, around 20,000 U.S. troops had entered Kure City and the area of Kaita-cho. According to the survey team’s reports, a declaration that restricted access by U.S. troops to Hiroshima City was still in effect at the beginning of the work, but toward the end, the city had been opened to military sightseeing tours.

The Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department had prepared guidelines (now held at the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives) ahead of time for residents near bases of the Allied Forces that warned residents to take precautions. The guidelines included such statements as, “Take precautions to avoid contact with foreign soldiers to the extent possible” and “Yell to neighbors for help if violence, looting, or other incidents occur.” However, people who were children at the time of the occupation report a variety of experiences.

Hirosuke Yokota, 83, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of four, said he had received sweets from occupation forces in the city, in imitation of the other children in the neighborhood who were given chocolate and chewing gum. He added, “I was surprised to find there was something as delicious as that. At the time, I never thought the United States was bad or anything like that.”

Masaki Hironaka, 85, a resident of Fukuyama City, confessed that he had thrown stones at an occupation force truck in his hometown of Fukuyama City, to which he had returned after the end of the war. Experiencing the atomic bombing at the age of five in Hiroshima, he lost his father, Hajime, 37 at the time, who was killed in the bombing on his way to work.

He remembers hiding in a wheat field, when a soldier got off the truck and fired a gun, with the bullet sailing over his head. He said, “I regret causing mischief, but I felt hatred for my father being taken from me.”

(Originally published on November 14, 2024)

In November 1945, members of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey team, a joint group made up of the U.S. Army and Navy, was investigating the status of devastation in Hiroshima City. Established the previous year, in 1944, by U.S. presidential executive order to analyze air raids that had been carried out on Germany, the team set about studying the “effectiveness” of the atomic bombings of Japan, among other aims. Around 30 members of a physical damage survey unit of the team began investigating the city area on October 14, work that lasted until November 26.

Among many photographs taken of destroyed buildings and bridges, some not directly related to the survey remain today. One taken on Aioi Bridge (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) near the hypocenter by H. J. Peterson, a member of the Navy’s photography unit, shows children receiving sweets from U.S. military personnel.

The process of stationing Allied Forces in Hiroshima Prefecture began in earnest on October 6. By the next day, October 7, around 20,000 U.S. troops had entered Kure City and the area of Kaita-cho. According to the survey team’s reports, a declaration that restricted access by U.S. troops to Hiroshima City was still in effect at the beginning of the work, but toward the end, the city had been opened to military sightseeing tours.

The Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department had prepared guidelines (now held at the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives) ahead of time for residents near bases of the Allied Forces that warned residents to take precautions. The guidelines included such statements as, “Take precautions to avoid contact with foreign soldiers to the extent possible” and “Yell to neighbors for help if violence, looting, or other incidents occur.” However, people who were children at the time of the occupation report a variety of experiences.

Hirosuke Yokota, 83, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of four, said he had received sweets from occupation forces in the city, in imitation of the other children in the neighborhood who were given chocolate and chewing gum. He added, “I was surprised to find there was something as delicious as that. At the time, I never thought the United States was bad or anything like that.”

Masaki Hironaka, 85, a resident of Fukuyama City, confessed that he had thrown stones at an occupation force truck in his hometown of Fukuyama City, to which he had returned after the end of the war. Experiencing the atomic bombing at the age of five in Hiroshima, he lost his father, Hajime, 37 at the time, who was killed in the bombing on his way to work.

He remembers hiding in a wheat field, when a soldier got off the truck and fired a gun, with the bullet sailing over his head. He said, “I regret causing mischief, but I felt hatred for my father being taken from me.”

(Originally published on November 14, 2024)