An anti-nuclear life, Part 10: Yoshiro Fukui (Western-style painter, 1912–1974)

Nov. 28, 2024

Burdened by “fate,” he created record of atomic bombing

Master of light and refined painting style

by Masakazu Domen, Senior Staff Writer

Yoshiro Fukui was a painter who played a leading role in Hiroshima’s Western art scene before and after the war. He experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima City while serving in the military. Because of the great sensation caused by his series “Pictorial Record of the Atomic Bombing,” which was released in Hiroshima and elsewhere after the end of the war, the title of “A-bomb painter” stuck with him.

Nevertheless, comments gathered from experts at the time of his death at the age of 62 and posthumous reviews of his artistic achievements contained words that pushed back against that view of the artist.

“He was not the kind of painter who should have created such art as A-bomb paintings. If he had been gifted a different place, he was someone who could have done even better work,” said Bungo Yoshida, a radio and television script writer. According to Yoshiko Harada, professor emeritus at Hiroshima Jogakuin University, “If he had not experienced the atomic bombing or created A-bomb paintings, he probably would have left behind many colorful, bright, and cheerful paintings like those of Renoir, his favorite painter.”

Although he was known as an A-bomb painter, Mr. Fukui exuded brilliance and charm as a genuine “painter” who could not be confined within that genre.

Mr. Fukui was born in the area of Danbara (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Minami Ward), at the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912). He loved painting from childhood and attended the Osaka School of Fine Arts. In 1928, while still a student at the school, Mr. Fukui’s work was accepted into the Imperial Art Exhibition (Teiten), drawing attention from the public. His paintings, including those he created around the time of his return to Hiroshima in 1931, were accepted into the exhibition a total of five times. He took on a leading role in the local Western art scene at a young age, establishing the Hiroshima Western Painting Institute with other painters, including Sho Yamaji (1903–1944), among other activities.

However, most of his youth coincided with the war period. About every two years after turning 20, he repeated a cycle of serving in the military mainly as a medic and creating artwork as a painter. During the Pacific theater of World War II, he was even dispatched to the war’s southern fronts on an Army hospital ship.

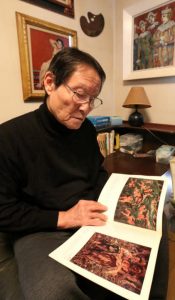

Kenji Fukui, 75, Mr. Fukui’s oldest son and an art director living in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, talked about this father. “He was not the brave type and did not create any paintings of the war. I think he was a man of culture from before the war, uninterested in politics but passionate about tango and chanson.”

On August 6, 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Mr. Fukui belonged to a medical unit of ground forces in the area of Nishikanon-machi (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward), located around 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. He later wrote his personal account of an experience in which he had been trapped under a collapsed building after the bombing and was pulled out from underneath by a military physician and a fellow soldier.

Mr. Fukui also left behind sketches of the horrific conditions after the atomic bombing he saw on the ground or created them from memory while the images were still fresh in his mind. The vividness of the sketches seem to have led to his sense of mission to someday turn them into paintings. In 1952 and 1953, he created six major art pieces in the series “Pictorial Record of the Atomic Bombing.”

Those paintings include “Small Children,” which depicts a group of children and a teacher suffering from burns over their entire bodies; “Showers,” featuring a mother, her baby, and a female student who had been soaked by the black rain; and “The Next Morning,” in which charred corpses, reddish-brown and swollen, are down on the ground. Recalling that experience, Mr. Fukui said, “All of the colors on this earth were peeled away, revealing colors I had never before seen in this world.” The series, difficult to position in his usual painting genre of which he was fond, which included bright scenes of the Setouchi area, seafood, and unclothed women.

In Kenji’s words, “Those works were not necessarily in his element, but they were paintings he could not avoid, given his fate as a witness.”

In 1961, just before turning 50, Mr. Fukui traveled to Paris, a place he had admired. Staying there for around three months, he freely painted city scenes and the people of Paris. Starting around 1968, he attempted to work on other major pieces featuring the atomic bombing. It was a time marked by continued poor health due to diabetes and other ailments, which could have been due to his experience in the atomic bombing.

One of the pieces, “The Anger of Hiroshima,” which he created in 1968, depicted a group of skeletons that appeared to be dancing around the A-bomb Dome. According to Kohei Tadani, 82, an artist living in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who studied under Mr. Fukui, the painter was intrigued by a skeleton specimen he saw at a hospital where he had been hospitalized. According to Mr. Tadani, Mr. Fukui had said, “I quickly made a sketch and turned into a painting.” He explained further, “I am a ‘true painter’ by nature.”

The series of A-bomb paintings he created in his later years was based in the color white, different from the strong colors he used in the “Pictorial Record of the Atomic Bombing.” Mr. Tadani said, “Those different colors might have resulted from Mr. Fukui’s weakening vision.” In the brush strokes of the dancing skeletons resides a light and refined tone. Mr. Tadani explained, “Different from the painting’s title, it shows the enjoyment he felt in painting the work, just as he always did.”

One wonders whether Mr. Fukui’s enjoyment of creating the paintings might have been his way of seeking revenge for the atomic bombing, which attempted to take his own life, or an expression of his “anger.” It might also have been a reflection of the mastery of Yoshiro Fukui as a “painter.”

Yoshiro Fukui

Mr. Fukui’s “Gansu Yokocho” series, carried in the Chugoku Shimbun between 1949 and 1961, and other works, were also popular as illustrations for their deep and evocative brushwork. In 1957, he became a founding member of the Shinkyo Art Association. His first work to be accepted in the Imperial Art Exhibition, titled “Hasu,” which he painted at the age of 16, is currently on display in an exhibition of archival works at the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum, in the city’s Naka Ward, through December 24.

(Originally published on November 28, 2024)