Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: In December, physician who experienced the A-bombing opens clinic in Hiroshima’s outskirts

Dec. 13, 2024

by Maho Yamamoto, Staff Writer

In December 1945, Masanori Todo, an ophthalmologist who died in 2004 at the age of 94, moved from the area of Shimoyanagi-cho (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward) to the village of Kodani in Hiroshima Prefecture (in present-day Higashihiroshima City), near his father’s hometown, and opened a clinic.

In anticipation of medical relief at the time of air raids, healthcare professionals in Hiroshima City were prohibited from evacuating outside the city, based on the “Air Defense Service Assignment Order” issued by the Hiroshima prefectural governor. According to a history of the Hiroshima City Medical Association, published in 1980, 270 physicians, accounting for 90 percent of all physicians in Hiroshima, had experienced the atomic bombing, with 225 of that number dying. Immediately after the bombing, 53 relief stations were set up at national schools and temples, where the surviving physicians provided treatment.

Mr. Todo had experienced the bombing in the city at his clinic, which doubled as his home. He worked on treating his younger brother, who suffered such symptoms as a high fever, subcutaneous bleeding, and hair loss. His condition improved with medicine and other treatments that had been moved away from the city, but when Mr. Todo gave him a blood transfusion, his brother experienced respiratory distress and died on September 6. Mr. Todo expressed his regrets in a personal account contained in the publication Hiroshima Ishi no Karute (in English, ‘Hiroshima physicians’ medical charts’), which was published in 1989. “If only I had not given him my blood,” he wrote.

After the situation in Hiroshima had settled down, he loaded his household goods and medicines onto a horse cart and moved to the village of Kodani. He rented a farm house and opened a clinic there. In the aforementioned account, he wrote, “The village had no physician at that time. With that, the townspeople appreciated my clinic’s opening. My expertise was ophthalmology, but I was fortunately able to imitate the work of internists and surgeons because I had served for a long time as a military physician.” When requested, he would visit patients at their homes in neighboring villages.

Land holders were able to receive stockpiled rice, and Mr. Todo revealed in the same personal account how he had opened his clinic in the village “with the aim of securing food.” In October 1946, he returned to the ruins of Hiroshima to make a fresh start. Hirotoshi Todo, 60, Mr. Todo’s grandson who has now taken over the clinic at the same location, recalled his grandfather. “Back then, regardless of specialty, my grandfather must have done whatever he needed to for his patients.”

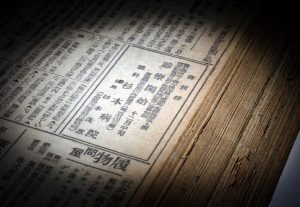

The Chugoku Shimbun published on December 14, 1945, carried an advertisement indicating that Sugimoto Ophthalmology Hospital—which had been located in the area of Onomichi-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), near the hypocenter—would begin accepting patients in the village of Kawauchi (in the city’s present-day Asaminami Ward).

(Originally published on December 13, 2024)

In December 1945, Masanori Todo, an ophthalmologist who died in 2004 at the age of 94, moved from the area of Shimoyanagi-cho (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward) to the village of Kodani in Hiroshima Prefecture (in present-day Higashihiroshima City), near his father’s hometown, and opened a clinic.

In anticipation of medical relief at the time of air raids, healthcare professionals in Hiroshima City were prohibited from evacuating outside the city, based on the “Air Defense Service Assignment Order” issued by the Hiroshima prefectural governor. According to a history of the Hiroshima City Medical Association, published in 1980, 270 physicians, accounting for 90 percent of all physicians in Hiroshima, had experienced the atomic bombing, with 225 of that number dying. Immediately after the bombing, 53 relief stations were set up at national schools and temples, where the surviving physicians provided treatment.

Mr. Todo had experienced the bombing in the city at his clinic, which doubled as his home. He worked on treating his younger brother, who suffered such symptoms as a high fever, subcutaneous bleeding, and hair loss. His condition improved with medicine and other treatments that had been moved away from the city, but when Mr. Todo gave him a blood transfusion, his brother experienced respiratory distress and died on September 6. Mr. Todo expressed his regrets in a personal account contained in the publication Hiroshima Ishi no Karute (in English, ‘Hiroshima physicians’ medical charts’), which was published in 1989. “If only I had not given him my blood,” he wrote.

After the situation in Hiroshima had settled down, he loaded his household goods and medicines onto a horse cart and moved to the village of Kodani. He rented a farm house and opened a clinic there. In the aforementioned account, he wrote, “The village had no physician at that time. With that, the townspeople appreciated my clinic’s opening. My expertise was ophthalmology, but I was fortunately able to imitate the work of internists and surgeons because I had served for a long time as a military physician.” When requested, he would visit patients at their homes in neighboring villages.

Land holders were able to receive stockpiled rice, and Mr. Todo revealed in the same personal account how he had opened his clinic in the village “with the aim of securing food.” In October 1946, he returned to the ruins of Hiroshima to make a fresh start. Hirotoshi Todo, 60, Mr. Todo’s grandson who has now taken over the clinic at the same location, recalled his grandfather. “Back then, regardless of specialty, my grandfather must have done whatever he needed to for his patients.”

The Chugoku Shimbun published on December 14, 1945, carried an advertisement indicating that Sugimoto Ophthalmology Hospital—which had been located in the area of Onomichi-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), near the hypocenter—would begin accepting patients in the village of Kawauchi (in the city’s present-day Asaminami Ward).

(Originally published on December 13, 2024)