Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: In mid-December, Chugoku Culture Alliance established

Dec. 17, 2024

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

In mid-December 1945, a group called the Chugoku Culture Alliance was formed at Yamamoto National School (present-day Municipal Yamamoto Elementary School) in the town of Gion-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward). In an attempt at cultural revival, poet Sadako Kurihara, who died in 2005 at the age of 92, and her husband, Tadaichi, who died in 1980 at the age of 73, invited literature enthusiasts living in Hiroshima and attracted around 60 participants. Among other topics, the group discussed the publication of an official magazine, titled Chugoku Bunka (in English, ‘Chugoku culture’).

Ms. Kurihara experienced the atomic bombing at her home in Gion-cho. She spent the entire night of August 8 talking at home with her husband and Tamiki Hosoda, a proletarian writer with whom she was on friendly terms and who died in 1972 at the age of 80. Even during the war, she had written and compiled tanka and other poems critical of the war. In a collection titled Kuroi Tamago (‘Black egg’), the complete edition of which was published in 1983, she wrote, “When the war is over, I’ll start a cultural movement. The reason the military started such a terrible and reckless war was that the people lacked a free culture. Because they offered no resistance.”

Mr. Hosoda was appointed to serve as one of the advisors to the group. In impressions he wrote in to the Chugoku Shimbun and that were carried in the newspaper on December 21, he said that, amid the city’s continued reconstruction, “The Chugoku Culture Alliance has sounded the first hammer struck amid the ruins of this Hiroshima.”

Initially, however, Ms. Kurihara was unaware that the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) had issued a press code of media censorship in September. When she spoke to a prefectural government official about her intent to publish a journal, she was told “don’t publish anything about the atomic bombings.” However, she wrote in ‘Black egg’ that, “It would be impossible for the post-war period to begin without any mention of the atomic bombings.” With strong determination, she went around asking people involved in literature to contribute their own works.

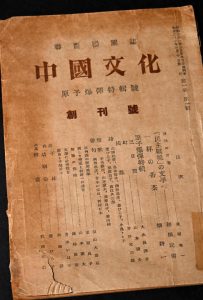

The journal was printed on low-quality, handmade paper obtained through bartering or at black market prices. The journal suffered no major deletions in the GHQ’s pre-print censorship process. Its first issue, titled “Atomic Bomb Special Edition,” was published on March 10, 1946. It contained Ms. Kurihara’s poem “Umashimenkana” (published in English as “We Shall Bring Forth New Life”), as well as works by around 100 people, including stories and tanka poems based on their experiences in the atomic bombings.

The journal preface carried Tadaichi’s writing. “Let’s send out this first issue to the world as an atomic bomb special issue. This is our duty, as we were born in Hiroshima, and these works of poetry belong only to us, we who are covered in wounds.” As one of the first literacy magazines or journals to convey the tragedy of the atomic bombings, it is believed that all 3,000 copies sold out.

(Originally published on December 17, 2024)

In mid-December 1945, a group called the Chugoku Culture Alliance was formed at Yamamoto National School (present-day Municipal Yamamoto Elementary School) in the town of Gion-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward). In an attempt at cultural revival, poet Sadako Kurihara, who died in 2005 at the age of 92, and her husband, Tadaichi, who died in 1980 at the age of 73, invited literature enthusiasts living in Hiroshima and attracted around 60 participants. Among other topics, the group discussed the publication of an official magazine, titled Chugoku Bunka (in English, ‘Chugoku culture’).

Ms. Kurihara experienced the atomic bombing at her home in Gion-cho. She spent the entire night of August 8 talking at home with her husband and Tamiki Hosoda, a proletarian writer with whom she was on friendly terms and who died in 1972 at the age of 80. Even during the war, she had written and compiled tanka and other poems critical of the war. In a collection titled Kuroi Tamago (‘Black egg’), the complete edition of which was published in 1983, she wrote, “When the war is over, I’ll start a cultural movement. The reason the military started such a terrible and reckless war was that the people lacked a free culture. Because they offered no resistance.”

Mr. Hosoda was appointed to serve as one of the advisors to the group. In impressions he wrote in to the Chugoku Shimbun and that were carried in the newspaper on December 21, he said that, amid the city’s continued reconstruction, “The Chugoku Culture Alliance has sounded the first hammer struck amid the ruins of this Hiroshima.”

Initially, however, Ms. Kurihara was unaware that the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) had issued a press code of media censorship in September. When she spoke to a prefectural government official about her intent to publish a journal, she was told “don’t publish anything about the atomic bombings.” However, she wrote in ‘Black egg’ that, “It would be impossible for the post-war period to begin without any mention of the atomic bombings.” With strong determination, she went around asking people involved in literature to contribute their own works.

The journal was printed on low-quality, handmade paper obtained through bartering or at black market prices. The journal suffered no major deletions in the GHQ’s pre-print censorship process. Its first issue, titled “Atomic Bomb Special Edition,” was published on March 10, 1946. It contained Ms. Kurihara’s poem “Umashimenkana” (published in English as “We Shall Bring Forth New Life”), as well as works by around 100 people, including stories and tanka poems based on their experiences in the atomic bombings.

The journal preface carried Tadaichi’s writing. “Let’s send out this first issue to the world as an atomic bomb special issue. This is our duty, as we were born in Hiroshima, and these works of poetry belong only to us, we who are covered in wounds.” As one of the first literacy magazines or journals to convey the tragedy of the atomic bombings, it is believed that all 3,000 copies sold out.

(Originally published on December 17, 2024)