Nihon Hidankyo’s path to Nobel Peace Prize, Part 3: Split in movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, resulting in two different survivors’ organizations with same name

Dec. 3, 2024

Organizations collaborate on submitting demands and collecting signatures

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

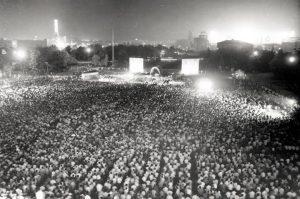

“I read aloud a manuscript that did not say what I had intended.” Akihiro Takahashi, who died in 2011, described the situation when he took the stage as a representative of atomic bomb survivors at the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held in Hiroshima City’s Peace Memorial Park (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward) on August 5, 1963. The content of his speech, which was drafted based on four pillars, including “opposition to nuclear testing by any nation,” ended up being “extremely empty” due to changes made at the behest of “executives” of the organization.

An appeal made by Mr. Takahashi and other atomic bomb survivors at the first World Conference in 1955 had led to the establishment of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) the following year. Seven years after its founding, the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, an inseparable element of the A-bomb survivors’ movement, found itself in turmoil due to disputes that had arisen among supporters of different political parties.

Began with Soviet Union nuclear test

First, supporters of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party and Democratic Socialist Party left the organization over issues involving revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960. Then, at the ninth World Conference meeting in 1963, confrontation between supporters of the Socialist Party, which opposed nuclear testing by “any nation,” and those of the Communist Party, which accepted the Soviet Union’s testing as a defensive measure for socialist countries against nuclear expansion by the United States, reached extreme levels and led to their split from the organization.

The author Kenzaburo Oe, who died in 2023, reported on the situation at that time in his publication titled Hiroshima Notes. Mr. Oe wrote about how, “The rupture has become rigid,” when Ichiro Moritaki, a member of the representative committee of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Hiroshima Gensuikyo) who died in 1994, read aloud a keynote report in which he described that the Japanese people had been crying out against “any nuclear testing by any nation.”

In 1964, the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo), affected by the confusion, split off from the group. Sixty years have passed since the division. Toshiyuki Mimaki, 82, chair of Hiroshima Hidankyo, said, “We do not intend to unite with the other group, what with the cautious view within our organization.” Kunihiko Sakuma, 80, chair of the other group established that year under the same name, Hiroshima Hidankyo, expressed his personal opinion that his group “has to think about the direction of reconciliation, as there is a possibility for development of our movement.”

The two Hiroshima Hidankyo organizations act together through the Hiroshima Alliance of A-bomb Survivor Organizations (Hidanren), an organization founded in 1974, when submitting their demands to Japan’s prime minister on the date of the atomic bombing and working to collect signatures.

Organizations hold separate sit-ins

Koshiro Kondo, the first secretary-general of Hidanren who died in 2002, lost his older brother in the atomic bombing. Masahiko, Koshiro’s 64-year-old son who lives in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, said, “My father might have thought that demands signed together by several organizations would have more impact.” When the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims was constructed based on the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, the Hidanren organization held repeated negotiations with the national government, leading to inclusion of the words “The people became victims (of the atomic bombing) because of mistaken national policy” in the hall’s explanatory plaque.

Nihon Hidankyo remains united as an organization, but according to its 50-year history, there were periods when its activities were suspended for times, particularly due to internal conflicts like the issue of withdrawal from the organization by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo). On the other hand, the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs (Gensuikin) and Gensuikyo, at one time part of the same organization, remain separated. The two held unified conventions from 1977 to 1985, but now continue to hold separate meetings, due to intensification of their dispute over operational policies.

In Hiroshima, both Tetsuo Kaneko, 76, a representative committee member of the Hiroshima prefectural chapter of Gensuikin (Hiroshima Gensuikin), and Nobuo Takahashi, 85, representative director of Hiroshima Gensuikyo, believe it is better to act together only for matters that are considered possible, rather than bringing the two organizations together. When staging sit-ins protesting nuclear testing in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, the Hiroshima Hidankyo led by Mr. Mimaki and Hiroshima Gensuikin do it together, as do the Hiroshima Hidankyo led by Mr. Sakuma and Hiroshima Gensuikyo.

In Nagasaki, there are three A-bomb survivors’ organizations, including the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Survivors Council, a member organization of Nihon Hidankyo, all of which have different campaign policies.

(Originally published on December 3, 2024)