Documenting Hiroshima of 1945: November 30, GHQ restricts Japan’s research

Nov. 30, 2024

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On November 30, 1945, the first briefing session of a special task force established by the Japan Ministry of Education’s Scientific Research Council to investigate damages resulting from the atomic bombings was held at Tokyo Imperial University (present-day University of Tokyo). The special task force, which was established on September 14 with the aim of conducting research through the collective efforts of Japan’s scientific community, had been carrying out studies on the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Representatives from a variety of fields, including Masao Tsuzuki, a professor of medicine, and Yoshio Nishina, a physicist, explained the current status of their work. Kyosuke Yamazaki, director of the science education bureau of the Ministry of Education mentioned that he hoped “to contribute to human civilization [through research].”

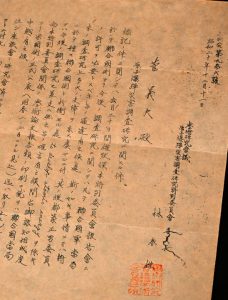

In response, officials from the economic and scientific section of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) who were present at the meeting, would issue a certain notification. According to a December 11 report made by Committee Chair Haruo Hayashi to those involved in the task group, “The notification was to the effect that all future studies and research would require permission from GHQ.” The notification also demanded that the printing of research papers involving the task force be suspended for the time being.

The same report indicated that Mr. Tsuzuki had negotiated with GHQ officials because the notification demands “would seriously hinder studies and research.” According to Hiroshima Shinshi (in English, ‘Hiroshima new history’), published in 1981 and based on interviews with him, Mr. Tsuzuki—who believed research would lead to medical treatments—made the following appeal. “Even at this moment I speak, many A-bomb survivors are dying one after another. … From a humanitarian perspective, banning the publication of research findings should not be allowed.”

As a result of such negotiations, field surveys were provisionally allowed during the period from February to August 1946. Although Mr. Tsuzuki kept negotiating with GHQ thereafter, Japan continued to be denied the freedom to present its own research results on the damages caused by the atomic bombings. GHQ had already imposed a press code censoring the media on September 19, 1945, and with that, strictly controlled information, including media coverage, on A-bombing damages.

The task force’s studies and research came to an end in fiscal 1947. However, it was not until 1953, the year following the end of Japan’s occupation, that the Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, a compilation of the papers of participating researchers, was published.

(Originally published on November 30, 2024)

On November 30, 1945, the first briefing session of a special task force established by the Japan Ministry of Education’s Scientific Research Council to investigate damages resulting from the atomic bombings was held at Tokyo Imperial University (present-day University of Tokyo). The special task force, which was established on September 14 with the aim of conducting research through the collective efforts of Japan’s scientific community, had been carrying out studies on the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Representatives from a variety of fields, including Masao Tsuzuki, a professor of medicine, and Yoshio Nishina, a physicist, explained the current status of their work. Kyosuke Yamazaki, director of the science education bureau of the Ministry of Education mentioned that he hoped “to contribute to human civilization [through research].”

In response, officials from the economic and scientific section of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) who were present at the meeting, would issue a certain notification. According to a December 11 report made by Committee Chair Haruo Hayashi to those involved in the task group, “The notification was to the effect that all future studies and research would require permission from GHQ.” The notification also demanded that the printing of research papers involving the task force be suspended for the time being.

The same report indicated that Mr. Tsuzuki had negotiated with GHQ officials because the notification demands “would seriously hinder studies and research.” According to Hiroshima Shinshi (in English, ‘Hiroshima new history’), published in 1981 and based on interviews with him, Mr. Tsuzuki—who believed research would lead to medical treatments—made the following appeal. “Even at this moment I speak, many A-bomb survivors are dying one after another. … From a humanitarian perspective, banning the publication of research findings should not be allowed.”

As a result of such negotiations, field surveys were provisionally allowed during the period from February to August 1946. Although Mr. Tsuzuki kept negotiating with GHQ thereafter, Japan continued to be denied the freedom to present its own research results on the damages caused by the atomic bombings. GHQ had already imposed a press code censoring the media on September 19, 1945, and with that, strictly controlled information, including media coverage, on A-bombing damages.

The task force’s studies and research came to an end in fiscal 1947. However, it was not until 1953, the year following the end of Japan’s occupation, that the Collection of Reports on the A-bomb Damage, a compilation of the papers of participating researchers, was published.

(Originally published on November 30, 2024)