Documenting Hiroshima, Witnesses to horrors of atomic bombing: Suffering of Yoshiaki Shimamoto, 89, persistent longing for family members lost in atomic bombing

Feb. 13, 2025

by Michiko Tanaka, Senior Staff Writer

Yoshiaki Shimamoto looks at a black-and-white photo placed in the family Buddhist altar every day. His parents, younger sister, and he as an elementary school student, look back at him from the photograph. Mr. Shimamoto, a former music teacher living in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture, celebrated his 89th birthday this month. No matter how old he gets, he still longs for his family members, whose lives were lost because of the atomic bombing. The time they spent together was too short, but they were happy. “I was loved. Yes, I think so,” he said.

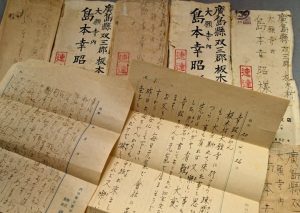

His father, Hisao, worked for a major construction company. He was serious about his children’s education, but also had a good sense of humor and often amused people. He loved music and was good at playing the mandolin. In the spring of 1945, when Mr. Shimamoto was in the fourth grade, he was evacuated to a temple in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. His father would write to him almost every week. The letters were always sent by express delivery, as he might have wanted to let his son read them as soon as possible.

Mr. Shimamoto’s mother, Shizuko, and sister, Keiko, who was four years younger than he, visited him at the temple in June. It was difficult to obtain enough food in those days. His mother picked red berries and filled a lunchbox with them for her children. She smiled as she watched them have their mouths full of the berries, but she did not eat a single berry herself. It was the first time Mr. Shimamoto tasted the sweet and sour flavor of the Nanking cherry. He still remembers it.

However, he never heard from them after August 6. His friends left the temple one by one taken by their relatives. Mr. Shimamoto’s aunt came to meet him in the winter of that year. It was the beginning of his life as an A-bomb orphan, which was too harsh for a nine-year-old boy.

◇

“I wouldn’t want to live the same life again,” Yoshiaki Shimamoto, 89, said clearly. He lives in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture. He lost his parents and younger sister to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and became an orphan at the age of 9. He moved from place to place in Hiroshima Prefecture, living with his relatives, foster parents, in an orphanage, and with a farming family as a live-in worker. As a teenager, he studied while working. It was a truly difficult time for him.

However, he says he never thought of killing himself. “My parents evacuated me because they wanted me to live.” He lived his post-war life desperately trying not to make his parents’ wish come to nothing.

Mr. Shimamoto was born in Osaka. His parents were both from the city of Hiroshima, but his father, Hisao, was often transferred to different places. His younger sister, Keiko, was born in Hsinking, Manchuria (now northeastern China), where their father was stationed at the time.

When war broke out between Japan and the United States, the family was in Osaka again. As the war situation worsened, Mr. Shimamoto alone evacuated to his mother’s parents’ home in Hiroshima in the spring of 1944. Later, his mother and sister joined him, and they moved to their own house in Eno-machi (now part of Naka Ward). After a short time, in spring of 1945, the evacuation of school children in groups began.

Mr. Shimamoto moved to Itaki Village (now part of the city of Miyoshi). He was separated from his family again. The letters he received from his father, who was stationed in Kyushu at that time, and his mother in Hiroshima, were the only psychological support for him.

“When will we be able to live together again? Let us all look forward to that day.” (Father) “Take care not to catch a cold while sleeping, look after yourself, and follow the instructions of your teacher. Look forward to the day when we can meet again.” (Mother)

However, that day never came. His aunt-in-law finally came to meet him in winter and took him to a temple in Suzuhari Village (now part of Asakita Ward), where he faced the ashes of his three family members. He heard they were all brought there after the atomic bombing, but his father died on August 24, mother on August 26, and sister on September 2.

Mr. Shimamoto felt particularly sorry for his sister, who was the last to die. “I think about the time when I was left alone after my parents died. She was only 5. She died without knowing what a caramel tastes like.”

Mr. Shimamoto was left alone, too. His aunt had lost her husband, who had been called up for military service, and she had her own children to support. He entered the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home in the town of Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward) in the fall of 1947.

The facility for orphans was established by the late Gishin Yamashita, a Buddhist. According to Mr. Shimamoto, small buildings dotted the premises, and seven or eight people lived together in each building. He was first assigned to the main hall of the temple on the premises. After finishing the cleaning in the morning, the next item in the daily routine was chanting sutras with some 80 people. Some of the children had scars from the atomic bombing, having keloids on their heads or having lost an eye.

He had a hard time getting used to his new life. Above all, he had a lingering attachment to the elementary school affiliated with Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now the elementary school affiliated with Hiroshima University), which he had attended while staying with his aunt. “I had to pass the exam to be admitted into the school. Thinking back, I had too much pride. I was tormented by thoughts like, ‘I’ve come down in the world’.”

This made him have an even more competitive mindset, and he came to set his mind on going to university. He wanted to deepen his studies and make something of himself. This was also a lesson he learned from his father, who was intent on giving his children a good education.

Mr. Shimamoto still has a diary from the time he started going to a local high school staying in the home for orphans. “This is the road to university. How can I be lazy? I will never give in to children who have parents. Damn it. I will go through with this! No matter what!”

At that time, there were also people who would support Mr. Shimamoto achieve his dream for the future.

(Originally published on February 13, 2025)

Yoshiaki Shimamoto looks at a black-and-white photo placed in the family Buddhist altar every day. His parents, younger sister, and he as an elementary school student, look back at him from the photograph. Mr. Shimamoto, a former music teacher living in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture, celebrated his 89th birthday this month. No matter how old he gets, he still longs for his family members, whose lives were lost because of the atomic bombing. The time they spent together was too short, but they were happy. “I was loved. Yes, I think so,” he said.

His father, Hisao, worked for a major construction company. He was serious about his children’s education, but also had a good sense of humor and often amused people. He loved music and was good at playing the mandolin. In the spring of 1945, when Mr. Shimamoto was in the fourth grade, he was evacuated to a temple in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. His father would write to him almost every week. The letters were always sent by express delivery, as he might have wanted to let his son read them as soon as possible.

Mr. Shimamoto’s mother, Shizuko, and sister, Keiko, who was four years younger than he, visited him at the temple in June. It was difficult to obtain enough food in those days. His mother picked red berries and filled a lunchbox with them for her children. She smiled as she watched them have their mouths full of the berries, but she did not eat a single berry herself. It was the first time Mr. Shimamoto tasted the sweet and sour flavor of the Nanking cherry. He still remembers it.

However, he never heard from them after August 6. His friends left the temple one by one taken by their relatives. Mr. Shimamoto’s aunt came to meet him in the winter of that year. It was the beginning of his life as an A-bomb orphan, which was too harsh for a nine-year-old boy.

◇

Parents, sister die

Becoming an orphan at age 9

Having a hard time getting used to life in orphanage

“I wouldn’t want to live the same life again,” Yoshiaki Shimamoto, 89, said clearly. He lives in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture. He lost his parents and younger sister to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and became an orphan at the age of 9. He moved from place to place in Hiroshima Prefecture, living with his relatives, foster parents, in an orphanage, and with a farming family as a live-in worker. As a teenager, he studied while working. It was a truly difficult time for him.

However, he says he never thought of killing himself. “My parents evacuated me because they wanted me to live.” He lived his post-war life desperately trying not to make his parents’ wish come to nothing.

Mr. Shimamoto was born in Osaka. His parents were both from the city of Hiroshima, but his father, Hisao, was often transferred to different places. His younger sister, Keiko, was born in Hsinking, Manchuria (now northeastern China), where their father was stationed at the time.

When war broke out between Japan and the United States, the family was in Osaka again. As the war situation worsened, Mr. Shimamoto alone evacuated to his mother’s parents’ home in Hiroshima in the spring of 1944. Later, his mother and sister joined him, and they moved to their own house in Eno-machi (now part of Naka Ward). After a short time, in spring of 1945, the evacuation of school children in groups began.

Mr. Shimamoto moved to Itaki Village (now part of the city of Miyoshi). He was separated from his family again. The letters he received from his father, who was stationed in Kyushu at that time, and his mother in Hiroshima, were the only psychological support for him.

“When will we be able to live together again? Let us all look forward to that day.” (Father) “Take care not to catch a cold while sleeping, look after yourself, and follow the instructions of your teacher. Look forward to the day when we can meet again.” (Mother)

However, that day never came. His aunt-in-law finally came to meet him in winter and took him to a temple in Suzuhari Village (now part of Asakita Ward), where he faced the ashes of his three family members. He heard they were all brought there after the atomic bombing, but his father died on August 24, mother on August 26, and sister on September 2.

Mr. Shimamoto felt particularly sorry for his sister, who was the last to die. “I think about the time when I was left alone after my parents died. She was only 5. She died without knowing what a caramel tastes like.”

Mr. Shimamoto was left alone, too. His aunt had lost her husband, who had been called up for military service, and she had her own children to support. He entered the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home in the town of Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward) in the fall of 1947.

The facility for orphans was established by the late Gishin Yamashita, a Buddhist. According to Mr. Shimamoto, small buildings dotted the premises, and seven or eight people lived together in each building. He was first assigned to the main hall of the temple on the premises. After finishing the cleaning in the morning, the next item in the daily routine was chanting sutras with some 80 people. Some of the children had scars from the atomic bombing, having keloids on their heads or having lost an eye.

He had a hard time getting used to his new life. Above all, he had a lingering attachment to the elementary school affiliated with Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now the elementary school affiliated with Hiroshima University), which he had attended while staying with his aunt. “I had to pass the exam to be admitted into the school. Thinking back, I had too much pride. I was tormented by thoughts like, ‘I’ve come down in the world’.”

This made him have an even more competitive mindset, and he came to set his mind on going to university. He wanted to deepen his studies and make something of himself. This was also a lesson he learned from his father, who was intent on giving his children a good education.

Mr. Shimamoto still has a diary from the time he started going to a local high school staying in the home for orphans. “This is the road to university. How can I be lazy? I will never give in to children who have parents. Damn it. I will go through with this! No matter what!”

At that time, there were also people who would support Mr. Shimamoto achieve his dream for the future.

(Originally published on February 13, 2025)