Documenting Hiroshima, Witnesses to horrors of atomic bombing: Yoshiaki Shimamoto Part 2, Enters university after working through school, supported by others

Feb. 14, 2025

by Michiko Tanaka, Senior Staff Writer

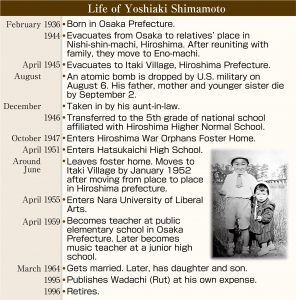

Yoshiaki Shimamoto, 89, a former music teacher living in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture, lost his family in the atomic bombing and became an orphan. During his junior high school years, he stayed at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home in present-day Saeki Ward. It was then that he was put in touch with a person he came to adore as his “mother.”

She was Vicki Zasar of Idaho, the U.S. She joined the “moral adoption” campaign advocated by Norman Cousins, the chief editor of a U.S. literary magazine. In the campaign, financial support was provided to A-bomb orphans from inside and outside the country. Ms. Zasar was introduced to Mr. Shimamoto through support groups in Japan and the U.S.

Letters exchanged between the two are stored in the Hiroshima Municipal Archives located in Naka Ward. They were found among the materials related to the orphan foster home. The first letter dated March 11, 1950, was from Ms. Zasar. It said, “I was very happy to receive a picture of a good-looking young boy and to know that I might write to him and, perhaps, help him in getting an education.” At the time, she was a 34-year-old single woman working at a radio station.

Mr. Shimamoto wrote about the foster home and his hobbies in his letters as he was asked. After he told her that he was interested in music, a large parcel arrived from the U.S. in January 1951. He wrote in his diary: “A violin has arrived from my foster mother. I am filled with deep emotion. How fortunate I am! My kind mother has finally granted my request.”

He also received private violin lessons outside the school, arranged by his junior high school music teacher. “I think the teacher also paid for the lessons. I was brought up by kind people.”

However, his communication with Ms. Zasar and the others ended soon after he entered high school. Mr. Shimamoto was troubled by human relationships within the orphanage, and when the only staff member he had trusted left the foster home, he also left the place in midyear 1951. He ended up moving from one place to another in Hiroshima Prefecture.

He first went to live with foster parents. But he did not get along with them and went to a child guidance center. After leaving the temporary shelter, he went to a farmhouse in the northern part of the prefecture, where he had made acquaintances while evacuated as an elementary school student. He worked there while attending a part-time high school. But he had never used a hoe before. He still has a scar on his leg from when a tendon was cut while using a farming tool. The work was tough, and he was made to work in the rice fields before his wound healed.

However, he never gave up his dream of going to university. At night, he would open his books under the light of the stable. Before his entrance exams, he rented an unoccupied house in the village and studied hard while earning money by working in the field to pay the rent. In the spring of 1955, he was accepted to Nara University of Liberal Arts (now Nara University of Education).

“My life finally began to stabilize,” said Mr. Shimamoto. But he said there was only a limited choice of occupations. If he became a teacher, he would not have to pay back his scholarship. He also thought, unlike in the private sector, he would be treated equally as a teacher even if he did not have parents. So, he became a public elementary and junior high school teacher in Osaka, where he spent happy days in his childhood. He worked there for 37 years.

On the other hand, he had turned his eyes from his memories of Hiroshima for a long time. He married a kindergarten teacher, and they had a daughter and son. It was his children that made him face his past. When his older child was in the fourth grade, he began to write in a literary magazine published by a group of teachers about his experience of becoming an orphan at that same age. In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, he published a book titled Wadachi (Rut).

His life had been spoiled by the atomic bomb. He does not want anyone else to share the same fate. “But Japan has not even filed a damage report, and is hiding behind the sword of nuclear weapons possessed by the attacker,” lamented Mr. Shimamoto. It is still painful for him to talk about the past, but he said he agreed to be interviewed with the intention of leaving his “will.”

Along with the family photos and letters, there is one other thing he cherishes: a wall clock his father bought in 1944 and put in their home in Hiroshima. At the time of the atomic bombing, the clock was at a relatives’ house in the suburbs. He gave it to the family of a farmer who had looked after him when he was a high school student. But more than 30 years later, he suddenly decided to ask them to let him have it again. It is a testament to the days he spent with his family. Now the clock ticks gently by his side.

(Originally published on February 14, 2025)

Yoshiaki Shimamoto, 89, a former music teacher living in Kawanishi, Hyogo Prefecture, lost his family in the atomic bombing and became an orphan. During his junior high school years, he stayed at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home in present-day Saeki Ward. It was then that he was put in touch with a person he came to adore as his “mother.”

She was Vicki Zasar of Idaho, the U.S. She joined the “moral adoption” campaign advocated by Norman Cousins, the chief editor of a U.S. literary magazine. In the campaign, financial support was provided to A-bomb orphans from inside and outside the country. Ms. Zasar was introduced to Mr. Shimamoto through support groups in Japan and the U.S.

Letters exchanged between the two are stored in the Hiroshima Municipal Archives located in Naka Ward. They were found among the materials related to the orphan foster home. The first letter dated March 11, 1950, was from Ms. Zasar. It said, “I was very happy to receive a picture of a good-looking young boy and to know that I might write to him and, perhaps, help him in getting an education.” At the time, she was a 34-year-old single woman working at a radio station.

Mr. Shimamoto wrote about the foster home and his hobbies in his letters as he was asked. After he told her that he was interested in music, a large parcel arrived from the U.S. in January 1951. He wrote in his diary: “A violin has arrived from my foster mother. I am filled with deep emotion. How fortunate I am! My kind mother has finally granted my request.”

He also received private violin lessons outside the school, arranged by his junior high school music teacher. “I think the teacher also paid for the lessons. I was brought up by kind people.”

However, his communication with Ms. Zasar and the others ended soon after he entered high school. Mr. Shimamoto was troubled by human relationships within the orphanage, and when the only staff member he had trusted left the foster home, he also left the place in midyear 1951. He ended up moving from one place to another in Hiroshima Prefecture.

He first went to live with foster parents. But he did not get along with them and went to a child guidance center. After leaving the temporary shelter, he went to a farmhouse in the northern part of the prefecture, where he had made acquaintances while evacuated as an elementary school student. He worked there while attending a part-time high school. But he had never used a hoe before. He still has a scar on his leg from when a tendon was cut while using a farming tool. The work was tough, and he was made to work in the rice fields before his wound healed.

However, he never gave up his dream of going to university. At night, he would open his books under the light of the stable. Before his entrance exams, he rented an unoccupied house in the village and studied hard while earning money by working in the field to pay the rent. In the spring of 1955, he was accepted to Nara University of Liberal Arts (now Nara University of Education).

“My life finally began to stabilize,” said Mr. Shimamoto. But he said there was only a limited choice of occupations. If he became a teacher, he would not have to pay back his scholarship. He also thought, unlike in the private sector, he would be treated equally as a teacher even if he did not have parents. So, he became a public elementary and junior high school teacher in Osaka, where he spent happy days in his childhood. He worked there for 37 years.

On the other hand, he had turned his eyes from his memories of Hiroshima for a long time. He married a kindergarten teacher, and they had a daughter and son. It was his children that made him face his past. When his older child was in the fourth grade, he began to write in a literary magazine published by a group of teachers about his experience of becoming an orphan at that same age. In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, he published a book titled Wadachi (Rut).

His life had been spoiled by the atomic bomb. He does not want anyone else to share the same fate. “But Japan has not even filed a damage report, and is hiding behind the sword of nuclear weapons possessed by the attacker,” lamented Mr. Shimamoto. It is still painful for him to talk about the past, but he said he agreed to be interviewed with the intention of leaving his “will.”

Along with the family photos and letters, there is one other thing he cherishes: a wall clock his father bought in 1944 and put in their home in Hiroshima. At the time of the atomic bombing, the clock was at a relatives’ house in the suburbs. He gave it to the family of a farmer who had looked after him when he was a high school student. But more than 30 years later, he suddenly decided to ask them to let him have it again. It is a testament to the days he spent with his family. Now the clock ticks gently by his side.

(Originally published on February 14, 2025)