Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In summer 1947, stationery from US reaches elementary school short of supplies

Jan. 28, 2025

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

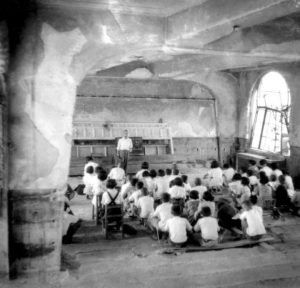

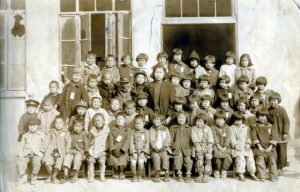

In the summer of 1947, students at Honkawa Elementary School, located near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day A-bomb Dome) in Hiroshima City, were busy studying hard. The windows of the steel-reinforced school building, located around 410 meters from the hypocenter, had been blown out, and their frames remained twisted. Some children had to sit on the floor because there were not enough chairs for everyone.

Children in harsh environment

“Concrete was exposed, and there was rubble on the playground,” said Hogusa Harada, 84, a resident of Akitakata City who was in second grade at the time, as she retraced her memories of that time. Her home was located in the area of Takajo-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) but, at the time of the atomic bombing, she was in what is now Asaminami Ward after being evacuated there, and survived as a result. In May 1947, she returned to live in the area of Sakan-cho (also in Naka Ward) and started attending Honkawa Elementary School. “In winter, snow came in through the windows, and some children had runny noses,” she explained.

The school had reopened in February 1946. According to a commemorative publication marking its 100-year anniversary and other information, the school restarted with a total of 45 students, including those from the Hirose school district. Kameji Yamamoto, the school’s assistant principal at the time, recalled in the publication that “classes resumed in name only.” He explained how there were no blackboards or floorboards and that “the children had to move their chairs to the right or left when it rained because of the badly leaking roof.”

Around 400 enrolled students, faculty, and staff at Honkawa National School, as it was known then, had been killed in the bombing. In January 1947, a helping hand came from someone in America, the country that had dropped the bomb. Howard Bell was an adviser to the Civil Information and Education (CIE) Section of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ).

Mr. Howard had come to inspect schools in Hiroshima City and, according to an article in the Chugoku Shimbun dated May 16, 1947, saw at Honkawa “children studying in the miserable schoolhouse with only iron frames, shivering in the cold wind.” Feeling “very sorry” for them, he donated 2,500 yen, along with 20 dozen pencils and six dozen colored pencils. He was described as having called on churches and other organizations back in the United States for contributions, leading to the delivery of stationery and sports equipment to the school.

Appreciation of mother’s love

Donated supplies were distributed by drawing lots. Ms. Harada won a yellow pencil with an eraser on the end, something she had never seen before. “It was too good to use. It smelled like soap,” she fondly recalled. Her friend received a notebook, which she wrote in and erased to use again.

“Thinking about it now, they were gifts from someone whose country killed my father, but it didn’t occur to me at that time to hold a grudge,” said Ms. Harada, who had lost her father, Kazuo Nakahara, 50, who was serving a member of a military news team, in the bombing.

Her mother, Natsue, who died in 1999 at the age of 92, opened a small shop and would work without complaint. She used to prepare a traditional school backpack for Ms. Harada, the fourth of her six children, and never missed a parent-teacher day at school. While grateful for her mother’s love, Ms. Harada said, “Losing my father is even more painful now.”

According to the fiscal 1947 Shisei Yoran, a guide to the city government, of the 40 national schools in Hiroshima City before the bombing, 19 had been burned to the ground and 12 severely damaged. A total of 187 classrooms in 11 schools were being housed in shacks, and 247 classrooms in 16 schools had been arranged by emergency repairs. However, due to the shortage of classrooms, students had to be divided into two groups and take classes in shifts. Policies of particular focus for the Hiroshima City government were the installation of roof tiles, repair of leaky roofs, and elimination of the two-shift class system.

(Originally published on January 28, 2025)

In the summer of 1947, students at Honkawa Elementary School, located near the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day A-bomb Dome) in Hiroshima City, were busy studying hard. The windows of the steel-reinforced school building, located around 410 meters from the hypocenter, had been blown out, and their frames remained twisted. Some children had to sit on the floor because there were not enough chairs for everyone.

Children in harsh environment

“Concrete was exposed, and there was rubble on the playground,” said Hogusa Harada, 84, a resident of Akitakata City who was in second grade at the time, as she retraced her memories of that time. Her home was located in the area of Takajo-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) but, at the time of the atomic bombing, she was in what is now Asaminami Ward after being evacuated there, and survived as a result. In May 1947, she returned to live in the area of Sakan-cho (also in Naka Ward) and started attending Honkawa Elementary School. “In winter, snow came in through the windows, and some children had runny noses,” she explained.

The school had reopened in February 1946. According to a commemorative publication marking its 100-year anniversary and other information, the school restarted with a total of 45 students, including those from the Hirose school district. Kameji Yamamoto, the school’s assistant principal at the time, recalled in the publication that “classes resumed in name only.” He explained how there were no blackboards or floorboards and that “the children had to move their chairs to the right or left when it rained because of the badly leaking roof.”

Around 400 enrolled students, faculty, and staff at Honkawa National School, as it was known then, had been killed in the bombing. In January 1947, a helping hand came from someone in America, the country that had dropped the bomb. Howard Bell was an adviser to the Civil Information and Education (CIE) Section of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ).

Mr. Howard had come to inspect schools in Hiroshima City and, according to an article in the Chugoku Shimbun dated May 16, 1947, saw at Honkawa “children studying in the miserable schoolhouse with only iron frames, shivering in the cold wind.” Feeling “very sorry” for them, he donated 2,500 yen, along with 20 dozen pencils and six dozen colored pencils. He was described as having called on churches and other organizations back in the United States for contributions, leading to the delivery of stationery and sports equipment to the school.

Appreciation of mother’s love

Donated supplies were distributed by drawing lots. Ms. Harada won a yellow pencil with an eraser on the end, something she had never seen before. “It was too good to use. It smelled like soap,” she fondly recalled. Her friend received a notebook, which she wrote in and erased to use again.

“Thinking about it now, they were gifts from someone whose country killed my father, but it didn’t occur to me at that time to hold a grudge,” said Ms. Harada, who had lost her father, Kazuo Nakahara, 50, who was serving a member of a military news team, in the bombing.

Her mother, Natsue, who died in 1999 at the age of 92, opened a small shop and would work without complaint. She used to prepare a traditional school backpack for Ms. Harada, the fourth of her six children, and never missed a parent-teacher day at school. While grateful for her mother’s love, Ms. Harada said, “Losing my father is even more painful now.”

According to the fiscal 1947 Shisei Yoran, a guide to the city government, of the 40 national schools in Hiroshima City before the bombing, 19 had been burned to the ground and 12 severely damaged. A total of 187 classrooms in 11 schools were being housed in shacks, and 247 classrooms in 16 schools had been arranged by emergency repairs. However, due to the shortage of classrooms, students had to be divided into two groups and take classes in shifts. Policies of particular focus for the Hiroshima City government were the installation of roof tiles, repair of leaky roofs, and elimination of the two-shift class system.

(Originally published on January 28, 2025)