Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — First Peace Festival, August 1947

Jan. 26, 2025

“I read out the peace declaration, hoping that even if the voice delivered from a corner of Hiroshima was small, it would reach people around the world.”

Peace Declaration, starting point of A-bombed city’s wishes

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, and Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

The first Peace Festival, held in August 1947, gave form to the wishes for peace welling up among Hiroshima’s citizens. A prospectus for establishment of the Hiroshima Peace Festival Association indicated, “All countries and people desperately hope that such a tragedy is never repeated in human history.” The first Peace Declaration, delivered by Hiroshima City’s mayor under the occupation of Japan led by the military of the United States, the nation that dropped the atomic bombs, warned of the threat of human extinction from nuclear war. Herein, the Chugoku Shimbun reviews the starting point of the A-bombed Hiroshima’s symbolic event, which continues to this day as the Peace Memorial Ceremony.

Hiroshima City Mayor Hamai argued “Nuclear war means destruction—revolution of thought is needed”

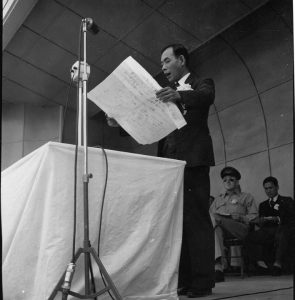

The first Peace Festival was held at Peace Plaza in the area of Nakajima-honmachi (what is now Peace Memorial Park, in present-day Naka Ward) in Hiroshima City on August 6, 1947. Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai read aloud the Peace Declaration, recalling the tragedy that had happened two years before then. “The first atomic bomb to be unleashed on a city in the history of mankind fell on Hiroshima; it instantly reduced the city to ashes and claimed the precious lives of more than 100,000 of our fellow citizens. Hiroshima turned into a city of death and darkness,” said Mr. Hamai.

Had his actions at the time of the bombing been slightly different, Mr. Hamai himself might have lost his life. His oldest son, Junzo Hamai, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward, said, “As someone who had survived, he strongly believed that the deaths of victims must never be in vain.”

On the night of August 5, 1945, Mr. Hamai, who was working as manager of the city government’s section charged with distributing rations, went to the city office in the area of Kokutaiji-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) in response to the sounding of an air-raid warning. In the very early morning of August 6, the warning was called off. He first thought about sleeping at his wife’s family home in the Nishidaiku-machi district (now part of Naka Ward), which was closer to the city office than his house, located in the area of Niho-machi (in the city’s present-day Minami Ward). But he changed his mind and returned to his own home. The atomic bomb detonated after he had awakened. He survived because his house was located more than three kilometers from the hypocenter, but his parents-in-law died at their home in the Nishidaiku-machi district.

Junzo, nine years old at the time, avoided the bombing altogether because he had been evacuated to the suburbs, returning to the city only after the war ended. He still remembers what his father had once muttered while hard at work securing provisions for A-bomb survivors amid the loss of many city employees to the bombing. “This kind of thing should never be repeated on earth,” he had said.

Mr. Hamai later became the first democratically elected mayor of Hiroshima City in April 1947, after serving as deputy mayor. In the publication Hamai Shinso Tsuiso-roku (in English, ‘Recollections of Shinso Hamai’), Taichi Takeuchi, a former city employee, testified that, “He personally revised the entire text of the Peace Declaration.”

On the day of the Peace Festival ceremony, Mr. Hamai said he felt himself straighten up as he continued reading the declaration. In his 1967 book titled Genbaku Shicho (in English, ‘A-bomb mayor’), he wrote, “I read out the peace declaration, hoping that even if the voice delivered from a corner of Hiroshima was small, it would reach people around the world.”

He emphasized in the declaration, “The people of the world have become aware that a global war in which atomic energy would be used would lead to the end of our civilization and extinction of mankind.” Calling it a “Revolution of Thought,” he pleaded for the creation of peace.

The Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) broadcast the ceremony live over the radio, which also made it to the United States as Japan’s first post-war international broadcast. The August 6 edition of the New York Times that year covered the peace festival while quoting Mr. Hamai’s speech. “Mayor Hamai said the three-day anniversary observance that began yesterday was designed to encourage rebuilding of the city with the object of making Hiroshima forever a symbol of the futility of war.”

Now with around 12,000 nuclear weapons still present in the world and amid persistent wars, Junzo pondered the Peace Declaration of 1947. His father served as Hiroshima City’s mayor for four terms, a total of 16 years, and he feels, “The first Peace Declaration epitomized the heartfelt cries of citizens after the atomic bombing.”

In December of last year, ahead of the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Junzo spoke at a gathering in Hiroshima organized by those involved in peace organizations in the city. At the gathering, he introduced the first Peace Declaration mixed with memories of his father. “I would like people to know more about the origins of the call from Hiroshima and to now spread the ‘Revolution of Thought’ toward a world of human coexistence without nuclear weapons or wars.” He has entrusted that desperate wish to future generations.

Period when criticism of A-bombings was not allowed

Told themselves bombings laid foundation for peace

The Peace Declaration of 1947 by Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai described the enormous number of deaths and destruction in the city caused by the atomic bombing. He added, “Yet as some slight consolation for this horror, the dropping of the atomic bomb became a factor in ending the war and calling a halt to the fighting.”

This passage is consistent with a statement written by then Mayor Shichiro Kihara in 1946, which was carried in the Chugoku Shimbun on August 6, 1946, the first anniversary of the atomic bombing. The statement read, “This sacrifice that our city endured has become the major driving force bringing peace to the world.” Adding that the victims “have become the human pillar of peace for the lasting welfare of all humanity,” Mr. Kihara wrote that he greeted August 6 with tears and feelings of gratitude.

Criticism of the dropping of the atomic bombs by the United States was unacceptable during the occupation of Japan. The texts of both mayors imply the thought that they were telling themselves, as their only solace, that the countless tragic deaths had laid the foundation for peace.

Hiroshima citizens experienced endless emotions of sorrow and anger. Mr. Hamai’s wife, Fumiko, who died in 2019 at the age of 105, lost her parents in the bombing. She later wrote in a personal account that, “I thought Americans were like devils, and my mind was obsessed with feelings of hatred.”

The Peace Declaration of 1947 did not include any direct expressions of emotion but described “the limitless sorrow” among citizens, arguing, “For only those who most bitterly experienced and came to know most completely the misery and the guilt of war can utterly reject war as the most terrible kind of human suffering, and ardently pursue peace.”

Under initiative of citizens, 45 events held at festival, including music, A-bomb disease checkups, and movies

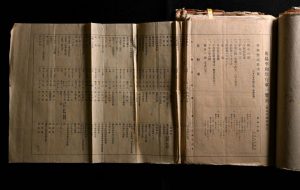

A concert performing the “Peace Song,” blood testing for A-bomb diseases, movies… The list of events for the first Peace Festival, now held at the Hiroshima Municipal Archive, contains 45 events held primarily during August 5–7, including the main ceremony. The organizers of the events were also diverse, such as civic cultural groups and hospitals.

Shinso Hamai first heard about the idea of holding a festival from Harushi Ishijima, who served at the time as chief of the NHK Hiroshima Central Broadcasting Bureau. Among a group of fewer than 10 friends and other members called the “Dream Tellers,” the idea was proposed as an opportunity to communicate to the world the resolve for peace of Hiroshima’s A-bombed citizens. In his book Genbaku Shicho (‘A-bomb mayor’), quotations hereinafter from same, Mr. Hamai recalled that time, writing about how the spirit of “we never ever want war again at any cost” etched into the hearts of the people served to drive their festival plans.

Approval for the idea also spread among business leaders in the city. Fujitaro Nakamura, chair of the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry, informed Mr. Hamai of rising momentum in favor of holding the festival. When Mr. Nakamura and Mr. Hamai together visited the occupation forces’ military government in the Chugoku region, headquartered in Kure City, its commander, dispatched from the British Commonwealth Forces, was said to have “agreed with the idea enthusiastically.” The Chamber of Commerce and Industry held a meeting of more than 200 representatives from relevant groups and proceeded with preparations.

The Hiroshima Peace Festival Association emphasized the idea of sending out a message to the world at the festival ceremony. A memorial service for the victims was held at a memorial tower for the war dead in Hiroshima and its chapel, both of which had been erected the previous year. Meanwhile, a costume parade and other events were held, drawing the ire of bereaved families, who called the activities “festival revelry.” Since there was a sense that the aims of the festival had not been clearly communicated to the groups working the festival events, Mr. Hamai wrote in his book, “We held a debriefing session after the festival and spent time reflecting on each other’s actions.” The following year, 1948, the festival’s events were revised.

Warnings of destructiveness and human extinction

General MacArthur sent message to festival

Peace Festival also covered by U.S. media, even as military expansion was accelerating

Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur sent to the Peace Festival his own message, which was read aloud at the ceremony. Mr. MacArthur held the rank of general, the highest military position in the United States, the nation that had dropped the atomic bombs, and was the supreme authority in occupied Japan. His message included the phrase, “Then over Hiroshima was launched a yet mightier weapon.”

The message continued, “For the agencies of that fateful day serve as a warning to all men of all races that the harnessing of nature’s forces in furtherance of war’s destructiveness will progress until the means are at hand to exterminate the human race and destroy the material structure of the modern world. This is the lesson of Hiroshima.”

Someone involved in the Hiroshima Peace Festival Association had requested that Mr. MacArthur send a message to the festival through his acquaintance at a U.S. news agency. It apparently was unusual for Mr. MacArthur to accept requests from local events. Toshikuni Nakagawa, former director of the Hiroshima Municipal Archive who is knowledgeable about Hiroshima’s history during the occupation period, shared his interpretation of Mr. MacArthur’s message. “I think his message was aimed at the U.S. and the rest of the world from a viewpoint that considered all of human history.” Regarding the content of the message warning of human extinction through destructive wars, Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai shared his interpretation in his book Genbaku Shicho (‘A-bomb mayor’), published in 1967. “It was reasonable,” he wrote.

In its August 6 edition, the U.S. newspaper the New York Times was one that carried the entire text of Mr. MacArthur’s message. In an editorial column, the newspaper emphasized, “We must hope and pray that those two cities (Hiroshima and Nagasaki) will remain forever the only habitations of men where such commemoration has to be made.” However, against a backdrop of concern about the Soviet Union’s nuclear development, it also argued, “Our main defense must still be the maintenance and strengthening of our pre-eminence in atomic energy.”

Around that period, the United States was advocating for the idea of “international controls of atomic power,” based on its concerns about nuclear proliferation. Mr. MacArthur’s message did not make any mention of the fact that the United States was the nation that had dropped the atomic bombs and that it was the only nuclear nation at the time, or any responsibility for the atomic bombings by the United States and its allies. Two years later, when the Soviet Union successfully conducted the country’s first nuclear test, the nuclear arms’ race escalated. During the period of the Korean War, which began in 1950, then U.S. President Harry Truman voiced the possibility of using nuclear weapons in the war.

(First Peace Declaration)

Today, on this second anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, we, Hiroshima's citizens, renew our commitment to the establishment of peace by celebrating a Peace Festival at this site, and expressing our burning desire for peace.

The citizens of Hiroshima will never be able to forget August 6, 1945. On that morning, exactly two years ago today, the first atomic bomb to be unleashed on a city in the history of mankind fell on Hiroshima; it instantly reduced the city to ashes and claimed the precious lives of more than 100,000 of our fellow citizens. Hiroshima turned into a city of death and darkness.

Yet as some slight consolation for this horror, the dropping of the atomic bomb became a factor in ending the war and calling a halt to the fighting. In this sense, mankind must remember that August 6 was a day that brought a chance for world peace. This is the reason why we are now commemorating that day by solemnly inaugurating a festival of peace, despite the limitless sorrow in our minds. For only those who most bitterly experienced and came to know most completely the misery and the guilt of war can utterly reject war as the most terrible kind of human suffering, and ardently pursue peace.

This horrible weapon brought about a ‘Revolution of Thought,’ which has convinced us of the necessity and the value of eternal peace. That is to say, because of this atomic bomb, the people of the world have become aware that a global war in which atomic energy would be used would lead to the end of our civilization and extinction of mankind. This revolution in thinking ought to be the basis for an absolute peace, and imply the birth of new life and a new world. We know that, when in a crisis discover a new truth and a new path from the crisis itself, by reflecting deeply and beginning afresh. If this is true, what we have to do at this moment is to strive with all our might towards peace, becoming forerunners of a new civilization.

Let us join to sweep away from this earth the horror of war, and to build a true peace.

Let us join in renouncing war eternally, and building a plan for world peace on this earth.

Here, under this peace tower, we thus make a declaration of peace.

Opening Remarks

Unveiling of Peace Tower

Peace Declaration

Peace Bell (Peace Prayer) (fireworks)

Allied Occupation Forces’ Message

Prefectural Governor’s message

Release of Pigeons

Peace Memorial Tree-planting

Handover of Peace Memorial Seedlings (to war-torn cities)

Peace Song Chorus

Closing Remarks (fireworks signal)

(Originally published on January 26, 2025)