Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: On May 20, 1949, Peace Park competition begins, with preservation of A-bomb Dome serving as symbol

Feb. 8, 2025

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On May 20, 1949, the Hiroshima City government began accepting applications for a competition to determine the design for a peace memorial park to be built near the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. Hiroshima City indicated in the competition guidelines for design of the park, “To meet the expectations of the world, Hiroshima City will be rebuilt as a world peace memorial city,” calling for design proposals aligned with that concept.

Designated national project

On May 10, just prior to the start of the competition, a special law known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was passed by Japan’s lower House of Representatives and, on May 11, by the upper House of Councilors. Positioning the reconstruction of Hiroshima as a national project to transform it into a peace memorial city, Article 3 of the law stipulated that the national government, local governments, public entities, and other relevant organizations should provide “every possible assistance.” The expectation was that such a measure would resolve the city’s pending issue of securing sufficient financial resources.

The bill was drafted by Tadashi Teramitsu, a native of Hiroshima City and then secretary-general of the House of Councilors, and proposed by members of the Diet. In accordance with the provisions laid out in Article 95 of the Constitution of Japan concerning special laws, the law would be promulgated and enter into force if a majority of Hiroshima’s citizens consented in a local referendum set for July of that year.

The proposed site for creating a peace memorial park, which the city planned as a pillar of its reconstruction based on the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, was the Nakajima district, located on the northern part of the delta between the Motoyasu River and the Honkawa River, and would include part of the east bank of the Motoyasu River. The location was the “center of the atomic bombing” and measured a total area of approximately 123,750 square meters (according to the application guidelines).

From appearances, most appropriate

Construction of the park on that site had been determined in the fiscal 1946 city reconstruction plan. Teizo Takeshige, chief of the City Planning Division of the Hiroshima Prefectural Government who was involved in the drafting of the plan, recalled that time in his personal account. “I was thinking about something that would convey the A-bombing tragedy to future generations,” he wrote. To that end, he said he had decided to include the area on the east bank of the Motoyasu River, where the remains of the devastation still stood, considering the largely destroyed Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day A-bomb Dome) to be “most appropriate from its appearance.”

At the time, however, the national government was in the process of demolishing buildings that remained in a precarious state in cities ravaged by the war. The Industrial Promotion Hall was included on the list of such buildings, with the budget estimate for its demolition already completed. Nevertheless, in his personal account Mr. Takeshige revealed that, “I put a halt to demolition of the dome at my own discretion and sent back the budget.”

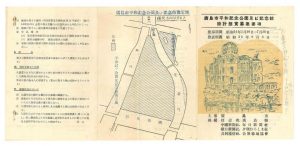

The policy of preserving the structure was maintained when Hiroshima City began accepting design proposals for a peace memorial park, stating in the application guidelines that the building “was planned to be left in place after appropriate repairs.” The cover of the pamphlet with the guidelines featured a large drawing of the Industrial Promotion Hall.

Hiroshima City also proposed construction of a peace memorial hall within the park, making that a condition for the design proposals. The main functions of the hall would be to serve “as a gathering place for the holding of a variety of international conferences for the world peace movement” and “as a display space compiling all materials related to the devastation caused by the atomic bombing, making them available for reference and research by peace lovers around the world.” In addition, the design conditions included construction of a tower for the hanging of a bell to sound prayers for peace.

Design proposals were solicited until the deadline of July 20, with 145 entries received. Nine people, including such experts as architect Hideto Kishida and representatives from local governments and the business community, served as judges. The results of the competition were announced on August 6, 1949, four years after the atomic bombing.

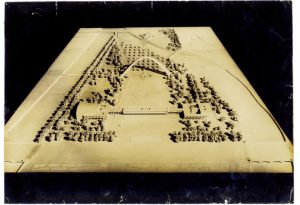

First prize was awarded to a proposal submitted by a group led by architect Kenzo Tange. Using the Industrial Promotion Hall as a symbol, the group’s design centered on a north-south “axis” connecting an arch-shaped tower and a peace memorial hall. It was at this time that the design concept of the present-day Peace Memorial Park, with the A-bomb Dome, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum arranged along a straight line, was created.

(Originally published on February 8, 2025)

On May 20, 1949, the Hiroshima City government began accepting applications for a competition to determine the design for a peace memorial park to be built near the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. Hiroshima City indicated in the competition guidelines for design of the park, “To meet the expectations of the world, Hiroshima City will be rebuilt as a world peace memorial city,” calling for design proposals aligned with that concept.

Designated national project

On May 10, just prior to the start of the competition, a special law known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was passed by Japan’s lower House of Representatives and, on May 11, by the upper House of Councilors. Positioning the reconstruction of Hiroshima as a national project to transform it into a peace memorial city, Article 3 of the law stipulated that the national government, local governments, public entities, and other relevant organizations should provide “every possible assistance.” The expectation was that such a measure would resolve the city’s pending issue of securing sufficient financial resources.

The bill was drafted by Tadashi Teramitsu, a native of Hiroshima City and then secretary-general of the House of Councilors, and proposed by members of the Diet. In accordance with the provisions laid out in Article 95 of the Constitution of Japan concerning special laws, the law would be promulgated and enter into force if a majority of Hiroshima’s citizens consented in a local referendum set for July of that year.

The proposed site for creating a peace memorial park, which the city planned as a pillar of its reconstruction based on the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, was the Nakajima district, located on the northern part of the delta between the Motoyasu River and the Honkawa River, and would include part of the east bank of the Motoyasu River. The location was the “center of the atomic bombing” and measured a total area of approximately 123,750 square meters (according to the application guidelines).

From appearances, most appropriate

Construction of the park on that site had been determined in the fiscal 1946 city reconstruction plan. Teizo Takeshige, chief of the City Planning Division of the Hiroshima Prefectural Government who was involved in the drafting of the plan, recalled that time in his personal account. “I was thinking about something that would convey the A-bombing tragedy to future generations,” he wrote. To that end, he said he had decided to include the area on the east bank of the Motoyasu River, where the remains of the devastation still stood, considering the largely destroyed Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day A-bomb Dome) to be “most appropriate from its appearance.”

At the time, however, the national government was in the process of demolishing buildings that remained in a precarious state in cities ravaged by the war. The Industrial Promotion Hall was included on the list of such buildings, with the budget estimate for its demolition already completed. Nevertheless, in his personal account Mr. Takeshige revealed that, “I put a halt to demolition of the dome at my own discretion and sent back the budget.”

The policy of preserving the structure was maintained when Hiroshima City began accepting design proposals for a peace memorial park, stating in the application guidelines that the building “was planned to be left in place after appropriate repairs.” The cover of the pamphlet with the guidelines featured a large drawing of the Industrial Promotion Hall.

Hiroshima City also proposed construction of a peace memorial hall within the park, making that a condition for the design proposals. The main functions of the hall would be to serve “as a gathering place for the holding of a variety of international conferences for the world peace movement” and “as a display space compiling all materials related to the devastation caused by the atomic bombing, making them available for reference and research by peace lovers around the world.” In addition, the design conditions included construction of a tower for the hanging of a bell to sound prayers for peace.

Design proposals were solicited until the deadline of July 20, with 145 entries received. Nine people, including such experts as architect Hideto Kishida and representatives from local governments and the business community, served as judges. The results of the competition were announced on August 6, 1949, four years after the atomic bombing.

First prize was awarded to a proposal submitted by a group led by architect Kenzo Tange. Using the Industrial Promotion Hall as a symbol, the group’s design centered on a north-south “axis” connecting an arch-shaped tower and a peace memorial hall. It was at this time that the design concept of the present-day Peace Memorial Park, with the A-bomb Dome, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum arranged along a straight line, was created.

(Originally published on February 8, 2025)