Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: September 25, 1949, geologist devotes himself to collection as A-bomb Reference Material Display Room opens

Feb. 12, 2025

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

On September 25, 1949, Hiroshima City opened the A-bomb Reference Material Display Room in a space within the Hiroshima City Central Community Hall, located in the area of Motomachi (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). An article in the Chugoku Shimbun dated September 30 reported that the exhibit included, “Between 600 and 700 items such as rocks, rooftiles, concrete, and plants, as well as statistical tables of the damage to the city.” The actual items displayed in the room showed the “changes that had occurred during the combustion and melting” caused by the thermal rays generated in the atomic bombing.

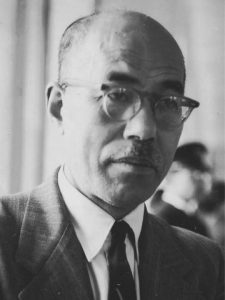

“Even though the room is small, those involved must be proud that it is the best collection room in the world,” described the article. The person who played a key role in opening the materials room was Shogo Nagaoka, a geologist at Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (present-day Hiroshima University) who died in 1973 at the age of 71.

ong>Entering Hiroshima following day ong>

According to his personal account titled Haikyo ni Tatsu (in English, ‘Standing in the ruins’), published in 1950, Mr. Nagaoka was in the present-day area of Kaminoseki-cho in Yamaguchi Prefecture for a geologic survey on August 6, 1945, when the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He had witnessed the mushroom cloud in the direction of Hiroshima. After returning to his home in present-day Otake City, he entered the devastated Hiroshima on August 7.

As a geologist, Mr. Nagaoka did not fail to observe the traces of intense heat evident in the rocks. As soon as he sat down on a lantern stone, he immediately felt pain as if impaled by needles. “Looking closely, I could see that the surface of the granite had melted … It wasn’t normal. I felt it must have been a special bomb,” he wrote in a description contained in the same account.

When he visited the university around 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, he found that the school buildings had been burned to the ground, with the minerals he had spent his life collecting broken and in tatters. It was then that his days of collecting A-bombed rocks and rooftiles began.

Toshiko Nakayama, 91, Mr. Nagaoka’s sixth daughter who lives in Fukuoka Prefecture, remembers her father returning home every day with his rucksack full. She said, “Our family didn’t understand why he was collecting all this junk and wondered what he wanted to do with it.” The number of items he brought home increased day by day, making it difficult to walk down the hallways of the house.

In 1948, Mr. Nagaoka was hired as a contractor by the Hiroshima City government, and he devoted himself to collecting and sorting the materials. In 1950, Hiroshima City opened the one-story wooden Atomic Bomb Memorial Hall, positioned next to the Hiroshima City Central Community Hall, and when the present-day Peace Memorial Museum opened in 1955, he became the museum’s first director. Ms. Nakayama said, “Now I understand how great a man my father was, because he stuck to his convictions.”

ong>Report of nuclear test ong>

Meanwhile, in September 1949, Hiroshima City compiled 107,854 signatures collected over a period of slightly more than 10 days calling on U.S. President Harry S. Truman to take action to prevent war, entrusting Norman Cousins, chief editor of an American literary magazine, with submission of the signatures. The same month, however, it became clear that the nuclear age was facing a new crisis.

The Chugoku Shimbun dated September 25 carried on its front page the headline “Atomic explosion in Soviet territory.” The article distributed U.S. President Truman’s special declaration dated September 23 in response to the Soviet Union’s first-ever nuclear test. It was later learned that the test had been conducted on August 29.

As the conflict with the Communist bloc intensified, President Truman stated at a Democratic Party meeting in April, “In the case where the welfare of the world and the welfare of the people in democratic countries were in jeopardy, I would not hesitate to decide to use an atomic bomb again.”

That was four years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. According to a current estimate made by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the number of U.S. nuclear warheads had reached 170 by 1949. Even as solidarity surrounding the “No More” idea began to grow among citizens of the A-bombed cities and those overseas, including the United States, the Cold War was intensifying between East and West, both of which possessed nuclear weapons. Then, in 1950, war broke out on the Korean peninsula.

(Originally published on February 12, 2025)

On September 25, 1949, Hiroshima City opened the A-bomb Reference Material Display Room in a space within the Hiroshima City Central Community Hall, located in the area of Motomachi (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). An article in the Chugoku Shimbun dated September 30 reported that the exhibit included, “Between 600 and 700 items such as rocks, rooftiles, concrete, and plants, as well as statistical tables of the damage to the city.” The actual items displayed in the room showed the “changes that had occurred during the combustion and melting” caused by the thermal rays generated in the atomic bombing.

“Even though the room is small, those involved must be proud that it is the best collection room in the world,” described the article. The person who played a key role in opening the materials room was Shogo Nagaoka, a geologist at Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (present-day Hiroshima University) who died in 1973 at the age of 71.

According to his personal account titled Haikyo ni Tatsu (in English, ‘Standing in the ruins’), published in 1950, Mr. Nagaoka was in the present-day area of Kaminoseki-cho in Yamaguchi Prefecture for a geologic survey on August 6, 1945, when the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He had witnessed the mushroom cloud in the direction of Hiroshima. After returning to his home in present-day Otake City, he entered the devastated Hiroshima on August 7.

As a geologist, Mr. Nagaoka did not fail to observe the traces of intense heat evident in the rocks. As soon as he sat down on a lantern stone, he immediately felt pain as if impaled by needles. “Looking closely, I could see that the surface of the granite had melted … It wasn’t normal. I felt it must have been a special bomb,” he wrote in a description contained in the same account.

When he visited the university around 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, he found that the school buildings had been burned to the ground, with the minerals he had spent his life collecting broken and in tatters. It was then that his days of collecting A-bombed rocks and rooftiles began.

Toshiko Nakayama, 91, Mr. Nagaoka’s sixth daughter who lives in Fukuoka Prefecture, remembers her father returning home every day with his rucksack full. She said, “Our family didn’t understand why he was collecting all this junk and wondered what he wanted to do with it.” The number of items he brought home increased day by day, making it difficult to walk down the hallways of the house.

In 1948, Mr. Nagaoka was hired as a contractor by the Hiroshima City government, and he devoted himself to collecting and sorting the materials. In 1950, Hiroshima City opened the one-story wooden Atomic Bomb Memorial Hall, positioned next to the Hiroshima City Central Community Hall, and when the present-day Peace Memorial Museum opened in 1955, he became the museum’s first director. Ms. Nakayama said, “Now I understand how great a man my father was, because he stuck to his convictions.”

Meanwhile, in September 1949, Hiroshima City compiled 107,854 signatures collected over a period of slightly more than 10 days calling on U.S. President Harry S. Truman to take action to prevent war, entrusting Norman Cousins, chief editor of an American literary magazine, with submission of the signatures. The same month, however, it became clear that the nuclear age was facing a new crisis.

The Chugoku Shimbun dated September 25 carried on its front page the headline “Atomic explosion in Soviet territory.” The article distributed U.S. President Truman’s special declaration dated September 23 in response to the Soviet Union’s first-ever nuclear test. It was later learned that the test had been conducted on August 29.

As the conflict with the Communist bloc intensified, President Truman stated at a Democratic Party meeting in April, “In the case where the welfare of the world and the welfare of the people in democratic countries were in jeopardy, I would not hesitate to decide to use an atomic bomb again.”

That was four years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. According to a current estimate made by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the number of U.S. nuclear warheads had reached 170 by 1949. Even as solidarity surrounding the “No More” idea began to grow among citizens of the A-bombed cities and those overseas, including the United States, the Cold War was intensifying between East and West, both of which possessed nuclear weapons. Then, in 1950, war broke out on the Korean peninsula.

(Originally published on February 12, 2025)