Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: On November 1, 1950, sudden death of stoic father, amid rising cases of leukemia

Feb. 18, 2025

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On November 1, 1950, Seigo Nishioka, now 93 and a resident of Hatsukaichi City, was a third-year student at Minami High School in Hiroshima City. As he sat in his first-period class, his homeroom teacher came to his seat and whispered that his mother had called to tell him his father had died. Upon hearing the sudden news, Mr. Nishioka rushed to the hospital in Kure City where his father had been hospitalized.

Before the atomic bombing, Mr. Nishioka had lived in the area of Nishihakushima-cho (in Hiroshima City’s present day Naka Ward) with his family of five, including his parents and two brothers. His father, Keizaburo, managed a transport business. “He was in the habit of saying that hard work would always bear fruit. He never complained, a true man of the Meiji era,” said Mr. Nishioka.

On August 6, 1945, experiencing the atomic bombing in front of Sentei Garden (present-day Shukkeien Garden), around 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, Keizaburo received injuries to his head when the branch of a pine tree was blown down in the bomb’s blast. He covered the bleeding wound with a cloth, returned to their home, and helped his wife, who had been trapped underneath. Mr. Nishioka, then a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical School (present-day Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School, following time as Minami High School), was exposed to the bombing’s thermal rays, suffering burns to his face.

Purple spots covered entire body

Losing their home and work, the family moved to the village of Ocho-son (in present-day Kure City) to stay with the parents of Mr. Nishioka’s mother. His father borrowed money to build a house and started a mandarin orange farm. Mr. Nishioka returned to his school in December 1945, commuting from a boarding house in Hiroshima. His father undid the stitches of his burned, tattered school uniform, from which he made a pattern and sewed new clothes for him.

Mr. Nishioka would help with the farm work when he returned home for extended school vacations. But in the summer of 1950, Keizaburo, who had been working hard to expand the fields, looked different. With the words, “I’m so fatigued,” he would lie down. Purple spots were visible over his entire body.

Mr. Nishioka was studying hard to get into university. However, at the end of that summer, his father told him with a grave expression, “I don’t have the energy to farm anymore. Please give up to going to college and get a job.” That was the first time he had heard his father show any signs of weakness.

About two months later, he received the news of his father’s death. Three days after Keizaburo had been admitted to a clinic affiliated with Hiroshima Prefectural Medical College (present-day Hiroshima University Hospital) in Kure City, he collapsed on his way to the washroom and died. He was 47 years old.

Mr. Nishioka rushed to the clinic and found his father lying in bed, his face covered with a white cloth. His mother, crying by his side, said, “Your father is dead,” and removed the cloth from his face. Mr. Nishioka recalled, “He looked like he always did when asleep. I couldn’t believe he was dead.”

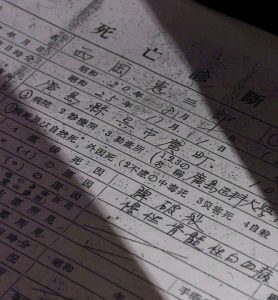

His father’s white blood cell count was abnormally high. On his death certificate, a physician listed the cause of death as “chronic myeloid leukemia,” with the date of onset indicated as “August 1945 (estimate).”

Effects of radiation exposure not well known at time

In accordance with his father’s wishes, Mr. Nishioka set about looking for work. He returned home for his school’s winter vacation with an informal job offer from a major textile manufacturer but, “When I said, ‘I’m home,’ my father wasn’t there. That’s when it first hit me that he had died.” He announced the job offer at the family’s Buddhist altar. “He would have been happy to hear the news had he been alive and well.” Even now his regret remains.

It is now believed that A-bomb survivors began to develop radiation-induced leukemia around two years after experiencing the bombing, with the number of cases peaking around six to eight years later. Around five years after the bombing, when Mr. Nishioka lost his father and Japan was under occupation—a time in which radiation effects on the human body were not understood to the extent they are today—numerous families were being torn apart by “A-bomb disease.”

(Originally published on February 18, 2025)

On November 1, 1950, Seigo Nishioka, now 93 and a resident of Hatsukaichi City, was a third-year student at Minami High School in Hiroshima City. As he sat in his first-period class, his homeroom teacher came to his seat and whispered that his mother had called to tell him his father had died. Upon hearing the sudden news, Mr. Nishioka rushed to the hospital in Kure City where his father had been hospitalized.

Before the atomic bombing, Mr. Nishioka had lived in the area of Nishihakushima-cho (in Hiroshima City’s present day Naka Ward) with his family of five, including his parents and two brothers. His father, Keizaburo, managed a transport business. “He was in the habit of saying that hard work would always bear fruit. He never complained, a true man of the Meiji era,” said Mr. Nishioka.

On August 6, 1945, experiencing the atomic bombing in front of Sentei Garden (present-day Shukkeien Garden), around 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, Keizaburo received injuries to his head when the branch of a pine tree was blown down in the bomb’s blast. He covered the bleeding wound with a cloth, returned to their home, and helped his wife, who had been trapped underneath. Mr. Nishioka, then a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical School (present-day Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School, following time as Minami High School), was exposed to the bombing’s thermal rays, suffering burns to his face.

Purple spots covered entire body

Losing their home and work, the family moved to the village of Ocho-son (in present-day Kure City) to stay with the parents of Mr. Nishioka’s mother. His father borrowed money to build a house and started a mandarin orange farm. Mr. Nishioka returned to his school in December 1945, commuting from a boarding house in Hiroshima. His father undid the stitches of his burned, tattered school uniform, from which he made a pattern and sewed new clothes for him.

Mr. Nishioka would help with the farm work when he returned home for extended school vacations. But in the summer of 1950, Keizaburo, who had been working hard to expand the fields, looked different. With the words, “I’m so fatigued,” he would lie down. Purple spots were visible over his entire body.

Mr. Nishioka was studying hard to get into university. However, at the end of that summer, his father told him with a grave expression, “I don’t have the energy to farm anymore. Please give up to going to college and get a job.” That was the first time he had heard his father show any signs of weakness.

About two months later, he received the news of his father’s death. Three days after Keizaburo had been admitted to a clinic affiliated with Hiroshima Prefectural Medical College (present-day Hiroshima University Hospital) in Kure City, he collapsed on his way to the washroom and died. He was 47 years old.

Mr. Nishioka rushed to the clinic and found his father lying in bed, his face covered with a white cloth. His mother, crying by his side, said, “Your father is dead,” and removed the cloth from his face. Mr. Nishioka recalled, “He looked like he always did when asleep. I couldn’t believe he was dead.”

His father’s white blood cell count was abnormally high. On his death certificate, a physician listed the cause of death as “chronic myeloid leukemia,” with the date of onset indicated as “August 1945 (estimate).”

Effects of radiation exposure not well known at time

In accordance with his father’s wishes, Mr. Nishioka set about looking for work. He returned home for his school’s winter vacation with an informal job offer from a major textile manufacturer but, “When I said, ‘I’m home,’ my father wasn’t there. That’s when it first hit me that he had died.” He announced the job offer at the family’s Buddhist altar. “He would have been happy to hear the news had he been alive and well.” Even now his regret remains.

It is now believed that A-bomb survivors began to develop radiation-induced leukemia around two years after experiencing the bombing, with the number of cases peaking around six to eight years later. Around five years after the bombing, when Mr. Nishioka lost his father and Japan was under occupation—a time in which radiation effects on the human body were not understood to the extent they are today—numerous families were being torn apart by “A-bomb disease.”

(Originally published on February 18, 2025)