Documenting Hiroshima of 1946: On February 19, surviving older sister also dies

Feb. 19, 2025

by Maho Yamamoto, Staff Writer

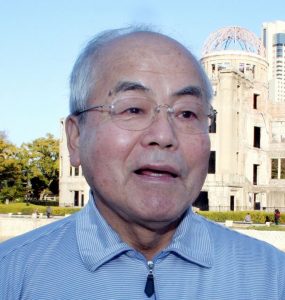

On February 19, 1946, Shozo Kawamoto, 11 at the time, who died in 2022 at the age of 88, lost his sister, Tokie, who was five years older and had experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. He had already lost five family members, his parents and other siblings, in the bombing. Tokie and he together had desperately struggled to survive in the aftermath of the war.

Tokie was working for Japan National Railways and experienced the bombing near Hiroshima Station (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Minami Ward). At their home in the area of Shioya-cho (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward), three members of the family, including his mother, died in the bombing, with the whereabout of his father and another older sister never coming to light. On August 9, 1945, Tokie went to the village of Kamisugi (in present-day Miyoshi City) to pick up Shozo, who at the time was a sixth-year student at Fukuromachi National School (present-day Fukuromachi Elementary School) and had been part of group evacuations of school children. She said, “Now that we two are all alone, I don’t want to live apart.” She rented a room in a building near the station, where they began living together.

However, in February 1946, Tokie fell ill, becoming no longer able to work, and passed away about one week later. She had experienced such symptoms as hair loss and uncontrollable bleeding, and Shozo said that later, “I started thinking it probably was leukemia.” According to Tsugumi Inoue, 24, a resident of Hiroshima’s Aki Ward who is a sixth-year student at the Hiroshima University School of Medicine and an “A-bomb Legacy Successor” (volunteers who convey the experiences of A-bomb survivors), Mr. Inoue was “anxious about being left alone and in such a state of shock that he couldn’t even shed tears.”

After his older sister passed away, Shozo found a job as a live-in worker at a soy sauce shop run by the village mayor, thanks to connections through his uncle, who lived in the village of Tomo (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward). When he was 23, the parents of a woman to whom he had proposed marriage rejected him. “We cannot let our daughter marry someone who was in Hiroshima at that time,” was the reason they gave. With that, he again made the decision to go it alone.

Still, with little desire to work seriously, he lived a rough life. In his early thirties, he lost his sense of purpose and went to Okayama with only 640 yen in his pocket, intending to find a place to die. In Okayama, he noticed a poster at an udon noodle shop that read, “Looking for a live-in worker.” Remembering his mother’s words, “Don’t give up. You can do it,” he found the strength to start over. At the age of 50, he became president of a food company.

When he returned to Hiroshima at the age of 70, he was deeply distressed that the reality of A-bomb orphans was not well known and began sharing his own experiences. He continued to think about the children who had been so hungry they would suckle on small stones and those who had lost their lives due to crime. In an A-bombing testimony filmed by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, he said, “Even without directly experience the atomic bombing, some children were unable to survive. I want you all to understand the reality of war.”

(Originally published on February 19, 2025)

On February 19, 1946, Shozo Kawamoto, 11 at the time, who died in 2022 at the age of 88, lost his sister, Tokie, who was five years older and had experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. He had already lost five family members, his parents and other siblings, in the bombing. Tokie and he together had desperately struggled to survive in the aftermath of the war.

Tokie was working for Japan National Railways and experienced the bombing near Hiroshima Station (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Minami Ward). At their home in the area of Shioya-cho (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward), three members of the family, including his mother, died in the bombing, with the whereabout of his father and another older sister never coming to light. On August 9, 1945, Tokie went to the village of Kamisugi (in present-day Miyoshi City) to pick up Shozo, who at the time was a sixth-year student at Fukuromachi National School (present-day Fukuromachi Elementary School) and had been part of group evacuations of school children. She said, “Now that we two are all alone, I don’t want to live apart.” She rented a room in a building near the station, where they began living together.

However, in February 1946, Tokie fell ill, becoming no longer able to work, and passed away about one week later. She had experienced such symptoms as hair loss and uncontrollable bleeding, and Shozo said that later, “I started thinking it probably was leukemia.” According to Tsugumi Inoue, 24, a resident of Hiroshima’s Aki Ward who is a sixth-year student at the Hiroshima University School of Medicine and an “A-bomb Legacy Successor” (volunteers who convey the experiences of A-bomb survivors), Mr. Inoue was “anxious about being left alone and in such a state of shock that he couldn’t even shed tears.”

After his older sister passed away, Shozo found a job as a live-in worker at a soy sauce shop run by the village mayor, thanks to connections through his uncle, who lived in the village of Tomo (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward). When he was 23, the parents of a woman to whom he had proposed marriage rejected him. “We cannot let our daughter marry someone who was in Hiroshima at that time,” was the reason they gave. With that, he again made the decision to go it alone.

Still, with little desire to work seriously, he lived a rough life. In his early thirties, he lost his sense of purpose and went to Okayama with only 640 yen in his pocket, intending to find a place to die. In Okayama, he noticed a poster at an udon noodle shop that read, “Looking for a live-in worker.” Remembering his mother’s words, “Don’t give up. You can do it,” he found the strength to start over. At the age of 50, he became president of a food company.

When he returned to Hiroshima at the age of 70, he was deeply distressed that the reality of A-bomb orphans was not well known and began sharing his own experiences. He continued to think about the children who had been so hungry they would suckle on small stones and those who had lost their lives due to crime. In an A-bombing testimony filmed by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, he said, “Even without directly experience the atomic bombing, some children were unable to survive. I want you all to understand the reality of war.”

(Originally published on February 19, 2025)