Survivors’ Stories: Hiroshi Shimizu, 82, Higashi Ward, Hiroshima City: His A-bomb testimony focusing on the “decade of void”

Mar. 17, 2025

Suffered from diarrhea in his childhood, and always said “I feel tired”

by Ikumi Yorikane, Staff Writer

There is a period that atomic bomb survivors call the “decade of void,” from immediately after the atomic bombing for about 10 years. It was a time when there was little support for the survivors from the Japanese national government and no organizations to rely on. Hiroshi Shimizu, 82, who experienced the bombing at the age of three and survived hard times with his mother and brother, focuses on this period, based on his mother’s memoir, as he talks about his A-bomb experience.

At that time, Mr. Shimizu was living with his parents. His older brother, who was in the second year of the advanced course at the national school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now Hiroshima University Attached Elementary School), had been mobilized to the town of Saijo in Hiroshima Prefecture (now part of Shobara) to help with farm work.

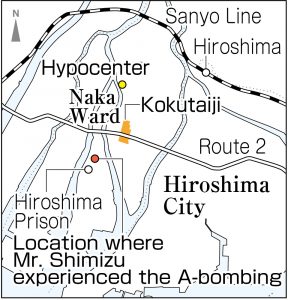

On the morning of August 6, Mr. Shimizu and his mother saw his father off to work at their home in Hiroshima’s Yoshijima-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. Suddenly, there was a flash of light, followed by a loud boom. Although his mother held Mr. Shimizu to her chest, they were buried under the building. When he was pulled out by his mother, who had desperately gotten out, it was pitch-dark outside.

On the way to Hiroshima prison, which became a shelter, he asked his mother what had happened to his clothes. “Even a three-year-old would have realized that something terrible must have happened,” Mr. Shimizu said.

The next day, they went to his father’s workplace in Kokutaiji-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to look for his father, who had not returned home, but his father’s name was not among the names of survivors written down. “I remember my mother praying with her hands pressed together in front of the rubble,” said Mr. Shimizu. However, they found him sunk down on the ground near their home. He was at work when the atomic bomb exploded and was injured all over his face by shards of glass, so he went to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital) to have the glass removed and then crawled back.

The three were able to live in a hut on the grounds of his uncle’s house in Nishikaniya-cho (now part of Minami Ward), and his older brother joined them. His father temporarily recovered enough to walk, but his strength seemed sapped after helping to repair the hut. He became bedridden and died two months later. His belly was bluish black, which Mr. Shimizu’s mother told him was because “he inhaled a lot of the gas from the bomb.”

After his father's death, the family lived a difficult life for about five years. His mother dug out the salt jar from their house that had burned down in a fire, divided the salt into small portions, and sold them in front of Hiroshima Station. Then, to raise two children, she started a business by renting a small stall in a black market, or worked in a factory. There was a time when the family had to live in the stall because they were evicted from the hut.

There were abnormalities in Mr. Shimizu’s health. He had diarrhea and severe nosebleeds for some time, and suffered from so-called “A-bomb lazy disease,” extreme fatigue and weariness unique to atomic bomb survivors. He had to sit out physical education class until he was in junior high school, and always said: “I feel tired.”

It was the time when the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) imposed the “press code” to strictly control media coverage, and the survivors were left alone without access to livelihood and medical support from home and abroad. The survivors themselves also did not speak out. Mr. Shimizu thinks seriously about the “decade of void” because he feels strongly that “the lives that could have been saved were not saved” during this period.

Mr. Shimizu served as a board member of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo) and the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) for two years from 2014. Regarding the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the Nihon Hidankyo, he thinks “the need to raise the voice for nuclear abolition is greater than ever.”

He has had problems with his spinal cord and kidneys since he was about 50, and an oxygen inhaler is now indispensable after he was hospitalized last year for pneumonia and heart failure. Through his experiences, he conveys the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, which he calls “the devil’s weapon.”

(Originally published on March 17, 2025)