Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In December 1950, ABCC conducts radiation effects studies on Hijiyama Hill, leaving some dissatisfied

Feb. 19, 2025

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

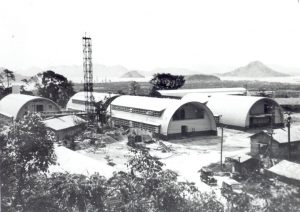

In December 1950, arch-shaped buildings of a configuration often used for U.S. military barracks appeared on Hijiyama Hill (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Minami Ward). The structures made up the new facility of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC; now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation), which set out to study the effects on the human body due to radiation from the atomic bombings by the U.S. military. The facility was equipped with examination rooms and laboratories.

Another facility established in Nagasaki following year

The Chugoku Shimbun on December 9, 1950, reported that the facility in Hiroshima was nearly completed, with full operations scheduled to begin the next year, in February 1951. According to the article, ABCC Director and U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Carl Tesmer revealed his hope that people would become familiar with and proud of ABCC, given its important connection to the medical work being done in Hiroshima City.

ABCC was a local research organization established by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences under a U.S. presidential directive issued in November 1946. The directive indicated that long-term research into effects from the atomic bombings was necessary. ABCC opened in March 1947, leasing part of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). The following year, ABCC also set up a facility in Nagasaki.

In the background was the U.S. military’s intense interest in the effects of the new weapons on the human body. The U.S. had dispatched survey teams to the A-bombed cities in September 1945, the month after the atomic bombings. A U.S.-led, joint Japan-U.S. survey team, which analyzed materials in the possession of and submitted by the Japanese side, was also formed. Based on the findings of such surveys, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy made a recommendation for the conduct of long-term research to U.S. President Harry S. Truman, who approved the recommendation and issued the presidential directive.

Shinso Hamai, who became Hiroshima City mayor in April 1947, initially believed it would be difficult for Japan alone to finance research leading to treatments for the A-bomb survivors and welcomed the idea of “establishing a research and study organization,” according to his book titled Genbaku Shicho (in English, ‘A-bomb Mayor’), published in 1967. ABCC conducted hematological studies and was staffed by Japanese physicians.

Meanwhile, there was growing dissatisfaction among citizens who had experienced the atomic bombing about the fact that ABCCC “does not provide treatment.” While hospitalized at the Red Cross Hospital, A-bomb survivor Kiyoshi Kikkawa had a blood sample taken and was asked about the circumstances under which he experienced the atomic bombing. “They didn’t provide any treatment whatsoever, and they didn’t even inform us of the test results,” wrote Mr. Kikkawa in his book titled Genbaku Ichigo to Iwarete (in English, “I was called ‘Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1’”), published in 1981.

“Scared of Americans”

Later, in 1948, ABCC moved into the former Gaisenkan building, which had housed the offices of the Army’s Shipping Command during the war, in the area of Ujina-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward). The organization’s work began to include other areas of research such as genetic effects in newborns and childhood development. Seigo Nishioka, 93, a resident of Hatsukaichi City who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 13 and lost his father to leukemia, was also asked to undergo testing at the facility when he was in high school. “During the war, we were taught that Americans were demons, so I was scared.” He said they made measurements of his entire body and took photographs of scarring from burns to his face and left hand.

Construction of ABCC’s new facility on Hijiyama Hill got underway in July 1949. Because there was a park on the site from the time before the war, the city government had proposed a different location. But ABCC preferred Hijiyama Hill because there was no risk of flooding on the site and other reasons, a position with which the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) agreed. In February 1949, the Hiroshima City Council voted in favor of the plan. The initial operating funds were provided by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

ABCC also requested that the Japanese government conduct a “nationwide survey of atomic bomb survivors” as a supplementary survey to Japan’s 1950 national census and initiated what is called the Life Span Study, used to confirm cause of death information, based on data from the survey. ABCC continued its work of conducting examinations of citizens at the new facility.

In the same publication, Mr. Kikkawa wrote, “For A-bomb survivors who could not survive the day without working, having to spend an entire day at ABCC for examinations presented a serious problem for their daily life.” After the occupation of Japan ended, demands for treatment began to surface.

(Originally published on February 19, 2025)

In December 1950, arch-shaped buildings of a configuration often used for U.S. military barracks appeared on Hijiyama Hill (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Minami Ward). The structures made up the new facility of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC; now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation), which set out to study the effects on the human body due to radiation from the atomic bombings by the U.S. military. The facility was equipped with examination rooms and laboratories.

Another facility established in Nagasaki following year

The Chugoku Shimbun on December 9, 1950, reported that the facility in Hiroshima was nearly completed, with full operations scheduled to begin the next year, in February 1951. According to the article, ABCC Director and U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Carl Tesmer revealed his hope that people would become familiar with and proud of ABCC, given its important connection to the medical work being done in Hiroshima City.

ABCC was a local research organization established by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences under a U.S. presidential directive issued in November 1946. The directive indicated that long-term research into effects from the atomic bombings was necessary. ABCC opened in March 1947, leasing part of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). The following year, ABCC also set up a facility in Nagasaki.

In the background was the U.S. military’s intense interest in the effects of the new weapons on the human body. The U.S. had dispatched survey teams to the A-bombed cities in September 1945, the month after the atomic bombings. A U.S.-led, joint Japan-U.S. survey team, which analyzed materials in the possession of and submitted by the Japanese side, was also formed. Based on the findings of such surveys, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy made a recommendation for the conduct of long-term research to U.S. President Harry S. Truman, who approved the recommendation and issued the presidential directive.

Shinso Hamai, who became Hiroshima City mayor in April 1947, initially believed it would be difficult for Japan alone to finance research leading to treatments for the A-bomb survivors and welcomed the idea of “establishing a research and study organization,” according to his book titled Genbaku Shicho (in English, ‘A-bomb Mayor’), published in 1967. ABCC conducted hematological studies and was staffed by Japanese physicians.

Meanwhile, there was growing dissatisfaction among citizens who had experienced the atomic bombing about the fact that ABCCC “does not provide treatment.” While hospitalized at the Red Cross Hospital, A-bomb survivor Kiyoshi Kikkawa had a blood sample taken and was asked about the circumstances under which he experienced the atomic bombing. “They didn’t provide any treatment whatsoever, and they didn’t even inform us of the test results,” wrote Mr. Kikkawa in his book titled Genbaku Ichigo to Iwarete (in English, “I was called ‘Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1’”), published in 1981.

“Scared of Americans”

Later, in 1948, ABCC moved into the former Gaisenkan building, which had housed the offices of the Army’s Shipping Command during the war, in the area of Ujina-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward). The organization’s work began to include other areas of research such as genetic effects in newborns and childhood development. Seigo Nishioka, 93, a resident of Hatsukaichi City who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 13 and lost his father to leukemia, was also asked to undergo testing at the facility when he was in high school. “During the war, we were taught that Americans were demons, so I was scared.” He said they made measurements of his entire body and took photographs of scarring from burns to his face and left hand.

Construction of ABCC’s new facility on Hijiyama Hill got underway in July 1949. Because there was a park on the site from the time before the war, the city government had proposed a different location. But ABCC preferred Hijiyama Hill because there was no risk of flooding on the site and other reasons, a position with which the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) agreed. In February 1949, the Hiroshima City Council voted in favor of the plan. The initial operating funds were provided by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

ABCC also requested that the Japanese government conduct a “nationwide survey of atomic bomb survivors” as a supplementary survey to Japan’s 1950 national census and initiated what is called the Life Span Study, used to confirm cause of death information, based on data from the survey. ABCC continued its work of conducting examinations of citizens at the new facility.

In the same publication, Mr. Kikkawa wrote, “For A-bomb survivors who could not survive the day without working, having to spend an entire day at ABCC for examinations presented a serious problem for their daily life.” After the occupation of Japan ended, demands for treatment began to surface.

(Originally published on February 19, 2025)