Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — In June 1950, Korean War begins; in August, Peace Festival is canceled

Feb. 16, 2025

“Amid the tense international situation today, I hope it is indicated to the world that the victims of the atomic bombing did not die in vain.”

Incessant flames of war amid cries from A-bomb survivors

by Minami Yamashita, Shimotaka Michio, and Yorikane Ikumi, Staff Writers

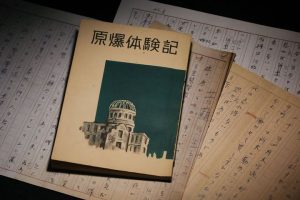

In the summer of 1950, the Korean War began, forcing the Hiroshima Peace Festival (present-day Peace Memorial Ceremony) to be canceled as a result of negotiations with the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). Amid such a situation, the Hiroshima City government compiled the collection Genbaku Taiken-ki (in English, ‘Accounts of A-bomb experiences’), the pages of which are inscribed with citizens’ vivid memories of the tragedy of five years before. On the Korean peninsula, which was under the threat of nuclear weapon use, there were some Koreans who had experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. Herein, we look back at a time in which citizens who endured hardship due to the bombing longed for peace even as they grew increasingly concerned about this new war.

Along with memories of tragedy, Ms. Kitayama inscribed anti-war message in personal account of A-bombing

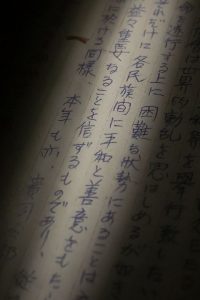

On July 1, 1950, Futaba Kitayama, 38 at the time, finished writing her Genbaku Taiken-ki, her personal account of the atomic bombing, in response to a call made by the Hiroshima City government for such accounts from the public. Ms. Kitayama had lost her husband in the atomic bombing and was raising three children in a makeshift shack next to the Aioi Bridge (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), located close to the hypocenter. Scarring from burns that had turned into keloids remained on her face and hands.

Naoko Kurokawa, 93, Ms. Kitamura’s oldest daughter who lives in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, revealed her feelings about those times. “As we had a close-up view of how our mother struggled to make a living, we children couldn’t even tell her when we had school trips.” Ms. Kurokawa remembers her mother massaging the scars on her left hand, so severe they made it hard to open her fingers, but does not recall seeing her mother ever writing her personal account. She added, “I wonder whether my mother might have been writing in the middle of the night.”

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Kitayama experienced the atomic bombing at the site where she had been engaged in building-demolition work around 1.7 kilometers east of the hypocenter. She wrote in the personal account submitted to the city, which is the source of other quotations below, about how when she wiped her nose and mouth with a hand towel after being exposed to the bombing’s thermal rays, “I was a shocked because I felt the skin on my face peeling off.” She added, with the skin of her fingers also hanging from her hands, “’Oh my goodness. I’ve been burned!’ I groaned from deep down in my soul.”

After receiving help from her older sister, she received medical treatment at a relief station in the village of Kamisugi village (in present-day Miyoshi City, Hiroshima Prefecture), where her relatives were living. Her husband, Kazuo Kitamura, 40 at the time, who was an employee of the Chugoku Shimbun, was brought to the same relief station after he experienced the bombing at a separate site for the work of building demolition. Despite having injuries seemingly less serious than those of Ms. Kitayama, he passed away on August 13.

Her children avoided effects from the bombing because they all had been evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. “My boy sat near my pillow and said, ‘Mom.’ Even now, recalling my desperate sorrow at that moment upon hearing his voice still makes me burst into tears.” She initially assumed her husband would survive even if she herself died, but (after her husband’s death) she continued to pray for her own life, thinking, “I must not die.”

A student of a girls school at the time of the bombing, Naoko took time off from school to care for her mother, who was wrapped head to toe in bandages. By the end of the year, Ms. Kitayama was able to walk again but, because of price hikes after the end of the war, “We were struck by hardship, which made me frantic,” she wrote in her account. In 1947, she managed to obtain employment at the Chugoku Shimbun, at a time when “mother and children were on the brink of living on the streets.” Hiroshima City solicited personal accounts of A-bomb experiences between June 20 and July 10, 1950, with the aim of “utilizing the precious experiences of citizens for contributing to the worldwide peace movement.” In her personal account she wrote six days after the Korean War had broken out, Ms. Kitayama concluded that, “Amid the tense international situation today, my hope is that the precious lives of 200,000 people sacrificed in the atomic bombing for peace were not in vain.”

However, in her handwritten manuscript, which is held at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives, there is an “x” in that part of the writing. It was not included in the published Genbaku Taiken-ki collection. Social circumstances at that time caused the cancellation of the Peace Festival, but details about the deletion of that part of her account, such as who did it and why, are not well understood.

“Countless corpses” and “It was a living hell”… For the Genbaku Taiken-ki collection, of the slightly more than 160 accounts submitted to the city, 18 accounts and summaries of 16 more were incorporated into Genbaku Taiken-ki. The publication was planned for broad distribution both in and outside Japan, but in the end, it was provided to only a limited number of those involved. Later, Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai wrote in his book Genbaku Shicho (‘A-bomb mayor’), published in 1967, that he had had no option but to delete that part from the account due to the “strict surveillance” of the materials conducted by the occupation forces.

Naoko lost her mother, who was 68 when she died, in 1980. Amid the persistent flames of war throughout the world, she said, “If my mother was alive now, she would want to express that last part.” She ponders the meaning of the words of her mother, who did not participate in specific movements but lived as one of the citizens who had experienced the atomic bombing. All the personal accounts submitted to the city government five years after the bombing are available at the Hiroshima Municipal Archives, including those ultimately not adopted for the collection.

Peace Festival scheduled to take place until immediately prior to date Canceled due to pressures from tense international situation

The Hiroshima City Peace Festival was held for three consecutive years, starting in 1947. The mayor’s Peace Declaration was always made as a call for the renunciation of war and the creation of a peaceful world from the perspective of human history. The General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) and the Commonwealth Forces would send a message or attend the festival in accordance with the city’s request. The Hiroshima Municipal Archives is in possession of a document in which is recorded the fact that the Hiroshima City government was planning once again to work to gain their support for the Peace Festival to be held in 1950.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee, comprised of Hiroshima City and other organizations, sent a document to GHQ’s Chugoku Regional Civil Affairs Department on July 17, 1950, to explain the significance of holding the festival and ask for their support, as they had done the previous year. “We believe it is becoming more and more important to make an effort to bring about peace and goodwill among different ethnic groups,” read the document.

On July 21, the Civil Affairs Department replied that it would gladly accept the association’s invitation to the festival. However, the situation apparently changed dramatically after that. When the Peace Memorial Service working committee held a meeting on August 2, it was reported that “the festival will be canceled in light of new circumstances.” The reason for the decision was explained to have been the result of negotiations with the “National Police (National District Police, present-day National Police Agency) Prefectural Regional headquarters director, and the City Police headquarters chief, in addition to the GHQ’s Civil Affairs Department.”

On the same day, Hiroshima City Deputy Mayor Tatsuro Okuda announced the cancellation of the Peace Festival, saying, “The festival has been canceled due to circumstances,” but did not provide specific reasons. News of the Peace Festival’s cancellation was also reported overseas. According to an article distributed by the Reuters news agency and carried in the U.S. New York Times newspaper published on August 6, 1950, if the festival were to have been held, it was feared that communists and others might take the opportunity to carry out undesirable activity.

Amid intensification of the Cold War, the so-called Red Purge, a movement to eliminate members of the Communist party, was growing within the United States. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, wrote in a book about how when he had visited the United States in 1948 and 1949, he was told that, “Those who engaged in peace activities were attacked unexpectedly, because they were thought to be allied with the Soviet Union.”

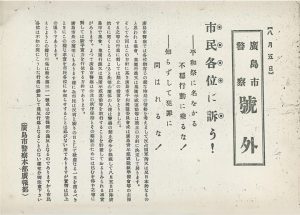

The GHQ strengthened its stance with respect to the same issue, forcing Japanese police to walk in lock-step. On August 5, after the festival’s cancellation was decided, the Hiroshima City Police distributed a flyer warning, “Do not engage in disruptive actions in the name of the Peace Festival!” The flyer also listed the names of specific groups wearing the mantle of peace, and called on people not to attend “any gatherings considered to be anti-occupation-forces or anti-Japan.” On August 6, the police arrested four people for distribution of “subversive flyers.”

Park Jeongsun, Korean survivor of Hiroshima’s A-bombing, could not live in peace even after returning home On June 28, 1950, three days after the Korean War had begun, Park Jeongsun, 15 at the time, who is now 90 and a resident of Busan City, was living in South Korea’s capital city of Seoul when he heard a roaring sound.

“It was a terrific boom. I thought another atomic bomb had been dropped.” The sound, however, originated from an explosion on the Hangang Bridge caused by the South Korean military. The detonation was intended to put a halt to an invasion carried out by the North Korean military, but it also took the lives of many citizens who were trying to cross the bridge to flee. Mr. Park, his older sister, and her husband, who were living all together, fled from Seoul with just the clothes on their backs.

Mr. Park was born in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture in 1934. His father worked at a factory to support his family back home after arriving in Japan from the Korean Peninsula, which had been annexed by Japan. Through an acquaintance, his father switched jobs to work at another factory in Hiroshima City. The rest of his family moved to Hiroshima in 1945, and they all lived in the area of Uchikoshi-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Nishi Ward) as a family of seven, including his parents and siblings. On August 6 that year, soon after their move, Mr. Park experienced the atomic bombing at their home. He was trapped underneath a pillar and, recalling that moment, he said, “My mother kindly wiped my bloody head with a cloth.”

The next year, the family returned to his parents’ hometown, which is now located in the province of Chungcheongnam-do in South Korea, but neither his father nor his mother were able to work because they were in poor health after experiencing the atomic bombing. For a time, Mr. Park worked at a factory. He said, “I picked and ate field mustard to fend off hunger.”

Driven by his desire to study, he moved to his married sister’s home and attended a junior high school in Seoul. Then the Korean War began. He escaped from the invasion by the North Korean military, returning to Chungcheongnam-do, around 100 kilometers from Seoul. His father was still unable to move freely, with the flames of war standing in the way of his recovery. Likely due to his frustration, Mr. Park’s father began to drink more and more. He died a short time after a ceasefire agreement was signed in 1953. At the time of his death, he was about to turn 50.

Later, as Mr. Park worked to provide for his three younger sisters, he continued to study and obtained a teacher’s license. He lamented, “If it had not been for war, my father would not have died that way. I was also deprived of a very important time for my study.” Based on his experience with two war-related hardships, he expressed his hope that, “A peaceful world can be achieved to ensure that everybody can finish their lives with human dignity.” The death toll of the Korean War until the ceasefire agreement was reached is said to have been several million people, and the war has never been declared over in terms of international law.

US hinted at possible use of nuclear weaponsnewspaper

Hiroshima City mayor called situation “unacceptable” in French newspaper

On the Korean Peninsula, Japan annexed the Korean Empire in 1910. After Japan’s defeat in the war in 1945, Korea’s south was occupied by the United States, with the north half occupied by the Soviet Union, dividing the country along the 38th parallel north. In 1948, South Korea and North Korea each proclaimed their establishment. The Korean War began after North Korea invaded South Korea.

Concerns grew about another use of an atomic bomb by the U.S. military, which headed the United Nations Forces supporting South Korea. In 1949, then U.S. President Harry Truman stated he would not hesitate to make the decision to use an atomic bomb again if such a decision had to be made for the welfare of the United States, and if the democracies of the world were at stake.

On July 16, 1950, during his trip to Europe to attend a Moral Re-Armament (MRA) world conference, Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai responded in an interview with a local newspaper in France, emphasizing, “We strongly raise our voice to oppose the U.S. military’s use of an atomic bomb in Korea.” He argued that use of nuclear weapons “is unacceptable anywhere in the world.”

However, in November, President Truman signaled possible use of nuclear weapons in the Korean War, suggesting that he was considering using an atomic bomb if it was “absolutely necessary.”

Japan became a backup supply base for the war, with U.S. troops stationed in Japan dispatched to the Korean Peninsula. According to an order from the GHQ, Japan established, in August 1950, a National Police Reserve, which later became the Japan Self Defense Forces. A draft constitution revealed by the GHQ to the Japanese government in 1946 strongly pushed for Japan’s demilitarization, an idea reflected in Article 9 of Japan’s current constitution. Despite that, the occupation policy would shift dramatically.

(Originally published on February 16, 2025)