Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: Late Ichiro Moritaki’s ‘Chronicle of disaster’ describes magnesium-like flash at time of bombing

Jan. 1, 2025

Tragedy passed on to future generations

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, and Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Ichiro Moritaki, who continued to call for the elimination of nuclear weapons and died in 1994 at the age of 92, used to say, “humanity cannot coexist with nuclear weapons.” Mr. Moritaki’s Saiyaku-ki (in English, ‘Chronicle of the disaster’) is the most precise record of his own experience in the atomic bombing. The journal in which he wrote on the morning of August 6, 1945, also remains today with traces of damage from the bombing. The tragedy of 80 years ago is clearly highlighted in the materials.

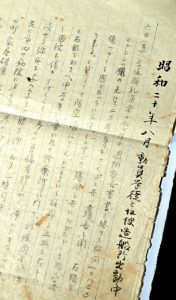

“The students’ morning assembly was held as usual. At the moment I finished writing my weekly report (8:20), I saw a magnesium-like flash. As soon as I took two or three steps back, I heard a roaring sound.” That passage was from his journal in the entry dated August 6.

Mr. Moritaki’s Saiyaku-ki (‘Chronicle of the disaster’) begins with a description of the instant his ordinary life in wartime was suddenly torn asunder. At that time, he was working as a professor at Hiroshima Higher Normal School (present-day Hiroshima University). On that day, he was leading students who had been mobilized for work from the school to a shipbuilding yard in the area of Eba-cho (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward), located around four kilometers from the hypocenter. While there, his right eye was pierced by a glass shard.

“Both sides of the road were aflame. The force of the fires was intense, and the blast of hot air was intolerable,” he described in the record. He was loaded onto a vehicle to take him to a hospital in the direction of the city center, but the vehicle was blocked by the fierce flames. He was then taken by boat to Miyajima Island (in present-day Hatsukaichi City), and cared for by his students through the night. The students wiped the blood from his wounds and cooled down his eye.

On August 8, when he entered the city to receive medical treatment, he learned of the unprecedented devastation caused by the bombing. “It was most tragic that several thousand male and female junior high-school mobilized students had been killed while lined up in the vicinity of the prefectural offices for building-demolition work.” Some of his colleagues at his school had also died.

On August 20, Mr. Moritaki moved to the village of Kimita-son (in present-day Miyoshi City), the location of his family home, and on September 9, he was admitted to an ophthalmic clinic in the town of Kisa-cho (also in Miyoshi City). The record of that span of time was compiled later based on his recollections, including the description, “People, one after another, are dying from A-bomb disease.”

Mr. Moritaki was in the habit of writing in his journals about a certain day the following morning. Right before the atomic bombing, he had placed the journal on a desk with the entry he was writing about August 5, including the description, “I made 500 bamboo spears.” The journal was torn by the A-bomb’s blast, and on one page there was ink from an ink bottle splattered here and there and marks from glass shards that had pierced the paper.

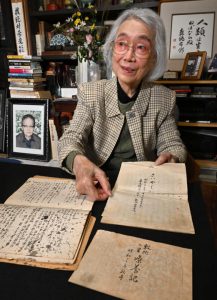

Mr. Moritaki’s second daughter, Haruko, 85, a resident of Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward who had lived together with her father, has since his death in 1994 held on to the enormous amount of materials he left behind in their home, including his journals written after the war. However, she looked for Saiyaku-ki (‘Chronicle of the disaster’) and the journal he had been keeping until August 5, 1945, because she was unaware of where the materials were located.

Ms. Moritaki said, “While experiencing the atomic bombing themselves, my father’s students took dictation of his spoken descriptions and cared for him. He survived because of their help, and he would cherish the records he had written at the time of the atomic bombing the most, as proof of the antinuclear path taken in the latter half of his life. With the materials now found, I have been able to fulfill my responsibility to pass on such information to future generations.”

(Originally published on January 1, 2025)