Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — August 1955, World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs

Mar. 16, 2025

“Is it right that one atomic bomb should kill innocent people, the elderly, children, and women so brutally?”

Determined to widely communicate psychological, physical suffering

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, and Fumiyasu Miyano, Staff Writer

In August 1955, 10 years after the atomic bombings, A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki spoke at the first World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held in Hiroshima City. The survivors conveyed to attendees gathered there from throughout Japan and overseas about their persistent suffering since the day they experienced the bombings. Not only had they suffered deep physical and psychological wounds as a result of the bombings, but they had also been forced to endure hardship in a society that lacked support from the national government. While those in attendance at the conference came into contact with the reality of the situation for the first time, a change began to take place in some survivors in their own thinking about related issues. The idea that the movement was composed of two inseparable elements — abolition of atomic and hydrogen bombs and relief for victims — began to be shared at that time.

Victims speak out, audience applauds

On August 6, 1955, the opening day of the World Conference, the Municipal Auditorium, the gathering’s main venue, located in Peace Memorial Park (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward), was filled to capacity, with around 1,900 people in attendance. Akihiro Takahashi, then 24, who died in 2011, spoke on behalf of the A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima.

“Is it right that one atomic bomb should kill innocent people, the elderly, children, and women so brutally? Surely, such an act is unforgivable, an enemy of humanity.”

Mr. Takahashi was in his second year at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School (present-day Motomachi High School) at the time of the bombing, when he suffered burns on his hands and feet while on the school’s grounds, around 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. Many of his classmates were killed. He survived after undergoing long-term medical treatment, but the burns left scars on his right hand, which he could no longer use freely. When he started looking for work, some companies rejected him because of his condition, a situation he described in his 1978 book Hiroshima, Hitori Kara no Shuppatsu (in English, ‘Hiroshima, starting out alone’).

After being hired as a temporary employee by the city government, he joined the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association in search of a place where he could feel a sense of belonging. The association was involved in the World Conference’s Hiroshima preparatory committee, some members of which were of the opinion that issues involving A-bomb victims should be addressed more seriously. Mr. Takahashi was asked to speak his mind freely.

He wrote in his book that, “While the conference participants sympathize with the idea of banning atomic and hydrogen bombs, they do not have profound knowledge about the reality of the atomic bombings.” He also spoke on behalf of other survivors who were struggling. “I have these burn scars on my upper body, as you can see, but there are people in Hiroshima who are in worse shape,” he said.

Misako Yamaguchi, representing the group called “Nagasaki Maidens,” spoke after Mr. Takahashi with tears in her eyes. “People who lost their mothers in the atomic bombing, or who don’t know what they would do if their mothers were to fall ill now, feel they would rather die. But if we were all to die now, who would tell people around the world about the horrors of the atomic bombings?”

The audience erupted in applause. Shizuko Abe, 98, an A-bomb survivor and resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, was at the World Conference. She said she was encouraged by the “kind eyes” of the attendees. “I had been feeling depressed because people would say things to me as if to rub salt in my wounds, but the people at the conference were kind.”

According to the recollections of Ichiro Moritaki, secretary-general of the Hiroshima preparatory committee, A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima voiced a desire for “more of our stories to be heard.” Based on negotiations with the World Conference’s organizing committee, discussions with survivors were hastily arranged before the conference deliberations were scheduled to take place at six venues on the second day of the conference. More than 10 survivors were assigned to each of the venues.

In the discussions, the survivors spoke about how, “I had lost my father, and when I went to look for a job or to take an exam, I was rejected because of A-bomb disease,” and about how, “For the first time, I said everything I wanted to say without hesitation.” The Chugoku Shimbun reported that participants from overseas had listened to the victims’ stories at each of the venues and came to feel that the stories “were not someone else’s problem” and that they “evoked sympathy.”

The conference was the start of discussions on the issue of nuclear weapons with an emphasis on the stories of victims, a trend that later spread to the United Nations and other organizations. Suzu Kuboyama, the wife of Aikichi Kuboyama, a crew member of the fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) who died after being exposed to radiation from U.S. hydrogen bomb testing, also spoke about the feelings of bereaved families.

The conference adopted a declaration on August 8, the last day of the gathering. The declaration read, “The unfortunate reality of the suffering of victims of atomic and hydrogen bombs must be widely known throughout the world. Only by banning atomic and hydrogen bombs can we truly help the victims.” Mr. Moritaki, himself an A-bomb survivor, was involved in drafting the declaration, which highlighted relief for the victims as “a foundation of the movement.”

In September, the nationwide organization based in Tokyo that had carried out preparations for the World Conference developed into the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. The second World Conference was held in Nagasaki City the following year, in 1956.

High school students participating from Chiba shocked

“Why have we abandoned these people until now?”

Recorded in published pamphlet

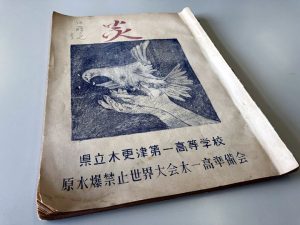

At the World Conference in Hiroshima City, many of the people in attendance were listening to the survivors’ vivid accounts of the atomic bombing for the first time. Hatsuo Tokita and four other students at Kisarazu First High School (present-day Kisarazu High School) in Chiba Prefecture attended the conference. The students wrote about their shock upon hearing the accounts in the pamphlet titled Honoo (‘Flame’), published in September 1955, the month after the conference.

“Why have we abandoned these people until now?” they wrote, adding, “Helping the victims is just as important as banning atomic and hydrogen bombs, and is something important we must do as Japanese citizens.”

Following the previous year’s Bikini Atoll disaster, students at the school made earnest efforts to collect signatures and donations for the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, supported by the school’s culture of independence and autonomy, and the desire for peace on the part of teachers who had experienced war. They formed their own preparatory committee ahead of the open of the World Conference, set for August 6, with four students selected to represent the prefecture and another student volunteering to participate. As for Hiroshima, amid insufficient lodging in the city, a local women’s association prepared private homes as accommodations for meeting participants as a way to enhance communication with them. Arrangements were made for students to stay at Seigan-ji Temple, located near the Hiroshima Municipal Auditorium, which served as the main venue for the conference.

The journal entries written by the conference participants and contained in Honoo record the events of the night before the opening ceremony. “In the evening, we had a friendly talk with members of the local women’s association (one-third of whom were A-bomb survivors). They told us about what it was like at the time of the bombing as well as their present situations. We were unable to listen to their stories without shedding tears.”

On the first day of the conference, the students listened to calls from representatives of the victims and, on the second day, at a local elementary school serving as an auxiliary venue, they learned of the hardships suffered by survivors. A Hiroshima man explained how, “My wife lost both eyes in the atomic bombing, and my daughter lost her right eye, so between us we have a total of three eyes.” A woman in her 20s from Nagasaki cried as she said, “I can’t marry because I’ve ended up with a face and a body like this.” Mr. Tokita wrote in Honoo, “Their stories sank deeply into our souls.”

On August 28, after their return home, the students held a debriefing session for the local community in Kisarazu City. The school newspaper also carried a detailed report on the victims’ testimonies. The school alumni association took over work involving publication of Honoo, with Katsuyoshi Kurihara, a 74-year-old local historian, shining a light on the work, leading to the publication’s registration in the official school history of Kisarazu High School. Mr. Kurihara said, “It was the honest and straightforward action of young people who had come into contact with the absurdity of the world.”

According to an official record of the conference, more than 2,300 people from 45 prefectures outside of Hiroshima participated in the event, excluding Okinawa, which was under U.S. rule. Although it was held as an international conference, it primarily served to broadly communicate the plight of the victims to the Japanese public.

Relief efforts organized in Hiroshima

Mr. Moritaki, who was involved in the preparations for the World Conference, recalled an impressive scene that took place immediately after the conference had ended. In his book Hankaku Sanju Nen (‘30 years of anti-nuclear activities’), published in 1976, he wrote about how, “A female A-bomb survivor rushed up to a window at the conference offices and shouted, ‘Mr. Moritaki, I’m so glad to be alive.’”

As recorded in his book Madotekure (‘Restore Hiroshima as it was’), Heiichi Fujii, one of those involved in the conference’s preparations, said that Yuko Murato, who experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and died in 2022, had expressed similar words. According to Ningen Meiboku (‘Majestic human trees’), published in 1997, after sharing her experiences in the bombing on the second day of the conference, Ms. Murato received a big round of applause and was so moved she cried out, “Ah, I’m not alone!”

In Hiroshima, that phrase became one of the guiding principles in the organization of relief efforts.

In November 1955, the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was established with the goal of coming up with a declaration for the World Conference. Seven people, including Mr. Moritaki, Hiroshima Prefectural Governor Hiroo Ohara, and Hiroshima City Mayor Tadao Watanabe were appointed to serve as representative council members, with 59 representatives from 54 organizations and groups in the prefecture also participating as standing council members. Established within the council was a subcommittee involving relief for A-bombing victims.

Mr. Fujii served as secretary-general of the relief subcommittee. In an article titled “We are just getting started,” which he contributed to the organization’s newsletter published in February 1956, he described his role. “The victims who attended the World Conference told us, ‘We were finally able to speak out about our 10 years of suffering. We are so glad to be alive.’ This subcommittee was born with the hope that these words would be shared by all the victims.”

The subcommittee placed an emphasis on activities related to “life.” It entrusted the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council with relief money donated by the Chinese delegation to the World Conference for use in the medical treatment of survivors. In response to requests from throughout the country to share the reality of the damages caused by the atomic bombings, survivors were sent to gatherings. “This activity has been greatly encouraging for the survivors, providing them with the ideas, ‘I’m glad to be alive’ and ‘I must live,’” as reported in the same newsletter.

Meanwhile, local organizations were formed within the prefecture. A survivors’ group in the Ashina district, located in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, was established in October 1955, after Noboru Inoue, who served as the group’s first chair, participated in the World Conference. The same year, other associations were formed in Otake City and in the Konu district in the northern part of the prefecture. The subcommittee began to work toward unifying all of the A-bomb survivors’ organizations in the prefecture with the aim of advancing the movement in which A-bomb survivors themselves took the initiative in demanding their own rights.

Inviting participants from both East and West

According to the Federation of American Scientists, in 1955, the United States possessed 2,422 nuclear warheads, the Soviet Union 200, and the United Kingdom 10. The number of nuclear weapons continued to increase amidst the confrontation between the U.S.-led capitalist camp (the West) and the Soviet Union-led communist camp (the East). The World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs invited participants from countries on both sides to address the issue of nuclear weapons as a crisis shared by all of humanity.

The Japanese government, because it was affiliated with the West, initially announced its intention to refuse entry into Japan of representatives from the communist bloc. However, because public sentiment against atomic and hydrogen bombs was running high, the government eventually allowed entry of representatives from the Soviet Union and China, nations with which diplomatic relations had not yet been restored, but not those from North Korea.

The World Conference also called for participation in Japan across party lines. Japan Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama, who led the ruling Japan Democratic Party (which merged with the Liberal Party in November 1955 to form the Liberal Democratic Party), sent a congratulatory message to the conference. Both right- and left-wings of Japan’s Socialist Party and members of the Communist Party spoke at the event.

The conference chairs were selected from among the participants from Japan, the U.S., Poland, and other countries. Shinso Hamai, who had served as mayor of Hiroshima for eight years until April of that year, gave an address on behalf of all the chairs. Mr. Hamai, who had renounced war in his city peace declarations, announced that the call for “No More Hiroshimas” must be considered in parallel with “No More Wars.”

In the 1997 edition of the journal “Hiroshima Peace Science,” Mr. Fujii remarked about how, “That idea should be carried on through the generations.” Mr. Fujii was involved in the preparations for the conference and served as the first secretary-general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations. Mr. Fujii’s idea of “war” included the damages Japan had inflicted on other countries through war, and he believed that “the ability to reflect on one’s own actions” was necessary to encourage sympathy among people around the world for the appeal to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs.

Part of World Conference Declaration

The unfortunate reality of the suffering of the victims of atomic and hydrogen bombs must be widely known throughout the world. Relief for such victims must be hastened through a worldwide relief campaign. This will serve as the true foundation of the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs. Only by banning atomic and hydrogen bombs can we truly help the victims.

We appeal to people around the world to further strengthen the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, regardless of differences in political parties, religions, or social systems.

(Originally published on March 16, 2025)