Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In June 1953, Genbaku ni Ikite (‘Surviving the A-bombing’) published

Feb. 26, 2025

Survivors’ physical and psychological scars, torment communicated to public

by Shimotaka Michio, Staff Writer and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

In June 1953, a collection of 27 personal accounts of atomic bomb survivors titled Genbaku ni Ikite (in English, ‘Surviving the A-bombing’) was published. The book was edited by Tomoe Yamashiro, a writer, and Takeshi Kawate, secretary-general of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association. It communicated the unhealed physical and psychological scars of A-bomb survivors and the adversity they faced in being virtually abandoned by society without relief provided by the national government.

One account, written by “Eriko,” revealed the writer’s deepening sense of isolation. “The world has become more peaceful, affluent, and beautiful than before but, with the feeling that my physical injuries will never heal, I am overwhelmed with the loneliness of being left behind by other people in this world.”

“If published anonymously”

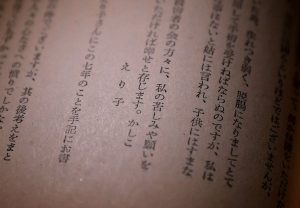

“Eriko,” the writer of the account, was Shizuko Abe, 26 at the time, a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward who is now 98. When Ms. Abe joined the association in the summer of 1952, after coming to know Kiyoshi Kikkawa, director of the group, Ms. Yamashiro had repeatedly asked her to write an account. Ms. Abe said, “I turned down the request at first but finally relented and said, ‘If published anonymously.’” Her writing was included in the publication in the form of a letter to a friend.

Ms. Abe had experienced the atomic bombing when she was 18. Despite suffering severe scarring to her face and hands, she gave birth to her first son in 1946 and a second son in 1949, devoting herself to raising the children with the support of her husband. However, she also became aware of the insensitive comments made by others around her.

The letter penned by “Eriko” described a situation in which, “Three young gangster-like men looked at me and burst into laughter, saying loudly to each other, ‘Hey, even a woman like that can have a baby.’ Imagine how I must have felt at the time. I would typically choose paths with low foot traffic to avoid meeting others, and in this case I simply walked on in sadness. Even being seen by others with my sad heart made me feel worse, so I walked along the embankment crying as I went, tears streaming down my face.”

At night, after other family members had gone to bed, she continued to write her account in bed amidst her tears. In the account, she revealed friction between her and her mother-in-law, who would insinuate that her experience in the atomic bombing was the reason for her children’s frail health. She said, “I wanted someone to understand my feelings through my account.” However, when she later received the published book and read her own section, she immediately burned it in their bath furnace. “It would have been an issue if someone in my family had ever found the book.”

Ms. Yamashiro and others paid visits to A-bomb survivors who faced hardships in daily life or because of illness and asked them to write their own personal accounts of the atomic bombing or offered to write an account on their behalf, capturing in words their feelings and emotions deep inside their hearts. Kichiro Ekyo, who was in his late 40s at the time and undergoing treatment at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), wrote Hakketsubyo to Tatakau (‘My fight against leukemia’) under his real name.

After Mr. Ekyo experienced the atomic bombing at his home around two kilometers from the hypocenter, he returned to what is now Akitakata City, where his mother was living. In June 1951, he suddenly felt dizzy while doing work on the farm and was later diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia. His oldest son paid for his hospital and medical expenses out of his salary, but they had to borrow money because it was not nearly enough. In the same account, Mr. Ekyo wrote, “I hope the government can establish a support system for those who suffer from A-bomb diseases so they can live pleasant lives with some sense of security.” He passed away in 1955 without ever seeing his wish come to fruition.

Opportunity to confront issue

The collection Genbaku ni Ikite (‘Surviving the A-bombing’) gave Hiroshima’s citizens a chance to confront the pain and sorrow of A-bomb victims, who had been neglected by the government despite efforts being made to tout Hiroshima as a “City of Peace.” Heiichi Fujii, who was in his late 30s at the time and worked as a social worker for the Hiroshima City government, later responded in an interview with Hiroshima University about how, “My main motivation was my shock upon reading Tomoe Yamashiro’s Genbaku ni Ikite,” as reported in Shiryo Chosa Tsushin (‘Data and research news’), published in 1981.

Mr. Fujii led the movement seeking relief for A-bomb survivors as the first secretary-general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), an organization formed in 1956. In the interview, Mr. Fujii added, “As a social worker, I thought ‘what is going on here’ and determined I had to work on the issue immediately. Almost all the main points of our current demands were covered in Genbaku ni Ikite.”

(Originally published on February 26, 2025)