Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In December 1953, Children’s Library completed

Feb. 28, 2025

Overseas support bears fruit in Motomachi

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

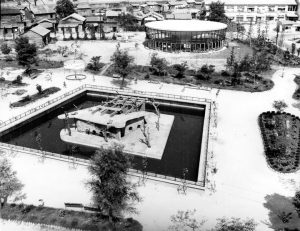

In December 1953, a children’s library was completed on a piece of land in the area of Motomachi (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward), which had been a military district before the atomic bombing. The library’s distinctive circular and glass-walled exterior was designed by Kenzo Tange, the architect who created the city’s Peace Memorial Park, and its bookshelves were filled with children’s and other books donated from overseas.

Sunlight streams into library

According to the 1952 Shisei Yoran, a guide to the city’s government, the Children’s Library, as it came to be called, was a single-story ferroconcrete building, with around 310 square meters of floor space and a design resembling a morning glory flower. Misako Tanabe, 84, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who once lived in municipal housing in the same Motomachi area, would visit the library nearly every day. She entered Kokutaiji Junior High School (in the city’s Naka Ward) in 1952 and recalled, “We used flimsy paper at school and at home, but all the books in the library were made of sturdy paper, which made me happy.” She especially enjoyed reading biographies.

Some children, not accustomed to the all-glass wall structure, would reportedly injure themselves by bumping into the glass. Recalling the library at that time, she said, “We were told to look for a door before entering.”

Support from overseas was instrumental to the creation of the library for children, which was a rarity in Japan at the time. Howard Bell, an advisor to the Civil Information and Education Section of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ), had visited Honkawa Elementary School to inspect the school near the hypocenter in 1947. In May 1949, he donated 1,500 children’s books to Hiroshima City after learning of a shortage of school supplies.

In response, in July, the city government opened the Children’s Library within the Asano Library (in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), the predecessor organization to the Hiroshima City Central Library. The Asano Library was rebuilt after it had been damaged in the atomic bombing. In 1950, the city received a donation of four million yen from the Southern California Hiroshima Prefectural Association in Los Angeles, an organization working to support Hiroshima’s recovery efforts, as a fund for construction of the library.

Ms. Tanabe had lost her home in the area of Higashisenda-machi (in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward) in the atomic bombing. Similarly, many private homes and books in schools had been destroyed in the fires after the bombing. Construction of the Children’s Library began amid this devastation. In December 1952, the library was not yet fully completed due to a lack of bookshelves and chairs, according to the Chugoku Shimbun dated December 8, 1952, but "unable to wait, people were allowed to look around at the books on an informal basis.” According to the 1953 Shisei Yoran, 39,000 people that year visited the library, which held 3,730 books in its collection.

Shouts of joy from children

In May 1948, the Hiroshima Children’s Culture Hall was completed nearby and used for school events and music concerts. In the fall of 1950, the city government and other organizations held the Hiroshima Children’s Exposition across the entire district, delighting children with an elephant from Thailand.

Meanwhile, the city had designated most of the ground west of the Motomachi area, where the Army’s West Drill Ground had been located during the war, as land for a park. However, to provisionally address a housing shortage, the city together with Hiroshima Prefecture and other organizations built 1,800 housing units, one of which became home to Ms. Tanabe. This post-war land-use policy shaped the entire Motomachi area, where education facilities and public housing were built after the war.

The Chugoku Shimbun dated August 17, 1956, carried a letter from a reader describing how the inside of the Children’s Library “felt like a sauna with its daylong mid-summer sunlight streaming in” due to its glass construction. The city considered putting up curtains, but such a drastic solution was difficult to arrange. Over time, the library became more cramped and could not expand its book collection, leading to it closing its doors in 1978. In 1980, the library was reborn as the Hiroshima City Children’s Library after being merged with the Hiroshima 5-Days Children’s Museum.

(Originally published on February 28, 2025)