Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In June 1952, production starts on A-bomb films

Feb. 22, 2025

Japanese government feared impact from depictions of devastation

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

In June 1952, production of the film Genbaku no Ko (in English, “Children of Hiroshima”) got off to a start in Hiroshima City. The film was based on a collection of personal accounts of the same title that had been published the previous year. Film production was led by the Kindai Eiga Kyokai company, and the screenplay was written by Kaneto Shindo, a native of Hiroshima’s present-day Saeki Ward who died in 2012 at the age of 100. Mr. Shindo also directed the film.

Mr. Shindo wrote in a submitted article to the Chugoku Shimbun dated July 6, “It was sad for those who remembered the time before the atomic bombing to witness the mountains of debris piled up on the shore.” Local children appeared in the movie, which used the area around the A-bomb Dome as one of the filming locations.

During Japan’s occupation by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), a press code had been imposed, with films also subject to censorship. However, Japan had had regained its sovereignty as an independent nation after the Treaty of San Francisco took effect on April 28, before the filming began. Children of Hiroshima became one of the first feature films shot in Hiroshima City to depict the devastation caused by the bombing.

The movie tells of the scars left by the bombing through a teacher, played by Nobuko Otowa, who had lost her family in the bombing and who visits her former kindergarten students in Hiroshima seven years after the tragedy. The film was screened in Hiroshima on August 6 seven years after the bombing, ahead of its nationwide release.

“Poem of anger”

At an informal discussion following the preview screening, Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai said, “I am grateful that the movie expressed what the people of Hiroshima wanted to say to the people of the world.” Mr. Shindo responded by saying, “I consider the movie to be a poem of anger.” Later, the film was released throughout Japan, and reverberations from the film spread around the country.

With the end of Japan’s occupation, the devastation caused by the atomic bombings was communicated in variety of ways. The August 6 edition of the photographic magazine Asahi Graph featured documentary photographs of the bombings, with that issue reprinted several times. In 1953, a report from a special task force investigating the destruction from the bombings set up by Japan’s Ministry of Education the month after the bombings was also published.

Meanwhile, the government, unable to completely free itself from the occupation period, took great pains to consider the United States. This became apparent after representatives of film companies selected two films, Children of Hiroshima and the short film Hiroshima Panels, about the paintings of the same title by Iri Maruki and his wife, Toshi, both artists, as Japan’s entries for the Cannes Film Festival to be held in France in the spring of 1953.

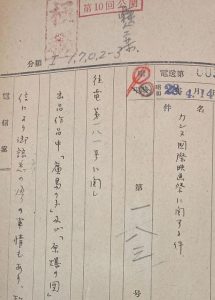

According to official telegrams sent by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Japanese Embassy in France, documents that are now stored in the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in Tokyo, the United States “is not in favor of” the films being entered in the film festival (in a cable dated February 10), and the American Embassy in Tokyo urged Japan “to do something to stop it” (February 16). The ministry also expressed concern that “the intention behind the production, the global impact of the films, and the misuse for politically motivated publicity are quite problematic” (February 16).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs ultimately decided not to prevent the films from being entered in the festival, fearing a backlash of public opinion, but it instructed the Japanese Embassy in France to speak privately to the festival organizer that it would refuse to accept the award if Children of Hiroshima, which had attracted more attention than the other film, appeared likely to win the prize (April 14). However, the Japanese Embassy made the determination to not intervene, thinking it would have the opposite effect by drawing more worldwide attention to the film.

Film withdrawn in strict secrecy

Meanwhile, out of consideration that “the screening of another A-bomb-related film would only provoke the United States and the festival organizing committee,” the Japanese Embassy asked the committee “not to show the Hiroshima Panels film” (according to Embassy’s June 9 report; hereinafter, the same), saying that “the Japanese film industry would not object so long as the decision to not show the film is done in strict secrecy.” The organizing committee, concerned about relations with the United States, agreed.

The Japanese Embassy reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “It is not a problem here that the film was not shown because it was short and the withdrawal was done secretly.”

(Originally published on February 22, 2025)