Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: September 29, 1954, early days of Hiroshima Carp baseball team

Mar. 4, 2025

Citizens show support for former mobilized student’s efforts

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

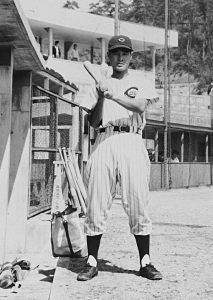

On September 29, 1954, Minoru Hasebe, 93, who is now a resident of Hiroshima’s Aki Ward, stood in the right-handed batter’s box in a game against the Tokyo Giants, held in Takamatsu City, as a 22-year-old player for the Hiroshima Carp baseball team. He was a backup catcher but, on that day, he got his chance to play. On the mound was Hiroshi Nakao, a left-handed starting pitcher for the Giants who would go on to win 15 games that year.

One hit leads to jubilation

“I took a chance that it would be a fastball.” Mr. Hasebe hit a liner to shallow right field for a base hit. Until then, he had been receiving only practice pitches and was not hitting well because of his lack of batting practice. That is why he said he “can’t ever forget” the hit that caused jubilation among the fans.

In 1945, nine years before the game, Mr. Hasebe was 13 and a second-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical School (present-day Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School). On August 6 that year, he was at his home in Hiroshima’s present-day Aki Ward, around nine kilometers from the hypocenter, because the munitions factory where he worked as a mobilized student was shut down for the day. “Light streamed all the way into the innermost room where my father and I were, surprising us. We thought a bomb had fallen in front of our house.” They watched the mushroom cloud as it rose from the bombing and the injured and wounded being transported on trucks.

The school’s wooden building in the area of Senda-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) had collapsed in the bombing but was spared from the fires. Desks and chairs that could be used were brought onto the schoolgrounds, and classes were held in the open air. Mr. Hasebe had joined the school baseball team around the end of his third year. The reason he decided to join the team was seeing some boys extorting lunches from people at the black market that had developed in front of Hiroshima Station. He thought, “If I just hang around doing nothing, I’ll end up just like them.”

After the school was merged with Minami High School, Mr. Hasebe became a catcher and cleanup hitter. When the Carp’s inaugural ceremony was held in January 1950, his coach told him to try out for the team, and he made it. He had been planning to work in a copper mine in which an acquaintance of his father was involved. However, Shuichi Ishimoto, then manager of the Carp, pressured him to join the team, saying “Just sign on.” In the end, Mr. Hasebe relented. “But the team didn’t have money,” he said. With no parent company behind it, the team ran into financial difficulties from the very first year. Payments of player salaries were delayed time and again. It was even rumored that the team would be sold or dissolved.

However, citizens initiated a fundraising campaign known as “Save the Carp,” and eventually support groups were formed in local communities and workplaces, leading to further increased momentum. Mr. Hasebe and other young players sold pencils with their autographs in the city’s commercial district to raise “funds to strengthen the Carp.”

Fundraising model

The team had overcome the financial crisis by 1954 as it entered its fifth year of existence. In February, before the start of the season, the team received coaching from Joe DiMaggio, the American professional baseball player known for his hitting, while he was visiting the city with his wife, the actress Marilyn Monroe. The team finished the season in fourth place, with Mr. Hasebe playing in 41 games, the most in his career, which continued through 1956.

What remains a vivid memory for Mr. Hasebe is a scene on their way home after a game at their Hiroshima home stadium in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward. From the bus window, he saw many fans with joyous expressions on the raised footpaths between the surrounding fields of green onions. “They were really cheering us on.”

In the same year, a signature campaign calling for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs gained momentum in Hiroshima following the Bikini hydrogen bomb test conducted by the United States. In the fall of that year, there was growing momentum to hold the World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in August 1955, 10 years after the atomic bombings. The decision to hold the conference was officially made in January 1955.

Local citizens in charge of preparations for the conference believed that the Hiroshima Carp could serve as a model for involving all of Hiroshima in enlivening the event. A draft of fundraising guidelines created by the Hiroshima Preparatory Committee for the World Conference (now held at the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives) described their aims. “We hope to recreate the enthusiasm for the Carp in our fundraising and in the boosting of the conference.”

(Originally published on March 4, 2025)