Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: March–April 1957, A-bomb survivors stage sit-in

Mar. 24, 2025

In protest of U.K. plan to conduct nuclear test

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

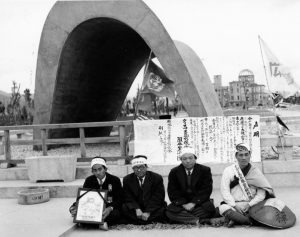

On March 25, 1957, a group of four people that included A-bomb survivors began a sit-in demonstration in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, located in Peace Memorial Park (in Hiroshima City’s present-day Naka Ward). The act represented a protest against the United Kingdom’s planned hydrogen bomb test in the waters around Christmas Island, part of the Republic of Kiribati, in the southern Pacific Ocean. The protesters has situated a written statement next to them as an appeal to Japan’s Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi and other leaders that read, “Stand in protest against the hydrogen bomb test.”

Three years had passed since the United States conducted a hydrogen bomb test on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, exposing fishing crews and local islanders to so-called “ashes of death” (radioactive fallout). The United Kingdom’s plan to conduct a test in the same area of the Pacific Ocean caused anxiety to spread throughout Japan, starting with people in the fishing industry.

The protesters, who based their sit-in on the theme “What the people of Hiroshima can do,” included Kiyoshi Kikkawa—a man who had become known as “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1” and was engaged in the campaigns carried out by the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo)—and his associate Ichiro Kawamoto. With the thought of staging the sit-in protest indefinitely until the test plan was cancelled, the protesters continued on with the protest the next day and thereafter by taking turns with each other. Local people and tourists provided them with drinks and snacks. Some people also joined in the sit-in spontaneously.

Sadako’s older brother also participated

One of those who joined the sit-in on March 30 was Masahiro Sasaki, 83 and a resident of Fukuoka Prefecture, who was 15 at the time and scheduled to enroll in Motomachi High School at the beginning of the school year in April. In 1955, Mr. Sasaki had lost his sister, Sadako, a survivor of the atomic bombing, to leukemia when she was 12. “I happened to pass by the protest during my spring vacation. I felt pure rage against the nuclear test,” said Mr. Sasaki.

On April 6, in response to a call made by Hiroshima Hidankyo, around a dozen people, including Heiichi Fujii, the organization’s secretary-general, and other A-bomb sufferers in Hiroshima Prefecture joined the sit-in. At its board of directors meeting held on March 28, Hiroshima Hidankyo considered the sit-in by Mr. Kikkawa and others to be an act representative of the group and made the determination to support the protest.

On April 20, the Hiroshima Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (chaired by then Hiroshima City Mayor Tadao Watanabe) held a rally in Peace Memorial Park for Hiroshima citizens to demand an end to atomic and hydrogen bomb testing. At the rally, a resolution was adopted calling on not only the United States and the United Kingdom but also the Soviet Union, which had conducted a hydrogen bomb test in 1955, to put a halt to their nuclear testing and conclude a nuclear test ban treaty. The nearly month-long sit-in ended that day, but the demonstration paved the way for subsequent sit-ins in protest against nuclear tests.

Prior to the rally, in early April, Japan’s national government sent Masatoshi Matsushita, a special envoy assigned by Prime Minister Kishi, to the United Kingdom. Mr. Matsushita called on then U.K. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan to halt the test, arguing that, “The feelings of the Japanese people, who experienced the disaster of nuclear weapons firsthand, should be taken into consideration.”

Despite that, on May 15, the United Kingdom decided to conduct the hydrogen bomb test. The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs began full-scale preparations to dispatch a National Delegation to call for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs in the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom. On June 30, 1957, Ichiro Moritaki, an A-bomb survivor and professor at Hiroshima University, and Tadao Ito, chair of the Hiroshima City Council, departed from Hiroshima as members of the delegation.

Japanese government not supportive of trip

However, the government hesitated to issue passports to members of the so-called National Delegation, including Mr. Moritaki and Mr. Ito. A government official in charge told the council that Prime Minister Kishi was “himself engaged in negotiations [to address the nuclear test issue] under sensitive international circumstances,” explaining that the government “was leaning toward opposing” the sending of a delegation from the private sector.

Amid growing public opinion demanding issuance of passports to the delegation, the trip to the Soviet Union was the first to obtain approval. Ultimately, the delegation’s visits to the United States and the United Kingdom were also approved. Mr. Moritaki, a member of the U.K. delegation team, visited the country in August and engaged in conversation with the critic Bertrand Russell and others about their campaign.

Mr. Ito, the city council chair and a member of the U.S. delegation team, visited New York and other cities. The report detailing that trip indicated that those engaged in the campaign to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs had been labeled communists, which made obtaining anticipated results difficult because of restrictions placed on the activities of Mr. Ito and the others. The report added that local U.S. citizens showed little interest in the campaign, indicating its concern that “American people have not been fully informed about the horrors of atomic and hydrogen bombs.”

(Originally published on March 24, 2025)