Documenting of Hiroshima, Witnesses: Michiko Matsui (Part 1)

Apr. 3, 2025

All young members gathered for the Ayumi group had gloomy eyes

A couple who helped the members open their minds were “benefactors”

by Michiko Tanaka, Senior Staff Writer

“I still have not forgotten what happened around that time, even though I was only nine then,” Michiko Matsui, 89, resident of Minami Ward, Hiroshima, said.

Ms. Matsui was the only daughter born in a family of a kimono fabrics dealer. Since spring of 1945, when she advanced to the fourth-grade at a national school, she had left her parents’ home in Fujimi-cho (now part of Naka Ward), and evacuated to Mitaki-machi (now part of Nishi Ward) with her grandparents.

On August 6 that year, she experienced the atomic bombing at the detached classroom of her school located in the neighborhood. After she crawled from the collapsed building, she dashed to her evacuation home, and found it had already caught fire. Her grandmother had burns on her upper body and face due to the atomic bombing. Ms. Matsui was also injured on her back as pieces of glass had become stuck in it.

From that night, she stayed in the burned-out site by spreading out a straw mat, and waited for her parents to pick her up. But they did not seem to appear. Her grandfather was missing, too, ever since leaving home the morning of August 6. Around August 10, she began to search for her parents with her grandmother, who was able to move a little again. On the way, she saw many miserable bodies, but did not think they were scary at all. She said, “Maybe my heart was numb at that time.”

In the middle of September, she picked up human remains which seemed to be those of her parents’ and her grandfather at the burnt ruins in Fujimi-cho. She said, “I am not sure if they were really their remains…” But she kept them near her pillow when she slept, after she settled in the home of her uncle who was discharged from military service and came back after the end of the war. In 1955, when she submitted a personal note to “a support group for Hiroshima children,” she described her love for her parents, writing, “What I always remember is my parents. I wish they were still alive no matter how many ugly keloids they may have had on their bodies.”

This project of collecting personal notes from A-bombed children led to the birth of the “Ayumi group,” for which young people, who had lost their parents due to the atomic bombing, got together. Ms. Matsui recalled how members had met for first time in fall of 1955. Everyone had gloomy eyes. Some did not speak at all. She said, “All of them had a terrible experience and stopped trusting others. Everyone shut down their minds to survive.”

She later came to know the members spent a harsh decade after the bombing. One woman had fed four younger siblings by doing daily-hired jobs since she had become an orphan when she was a first-year student at a girl’s school. Another member had six ribs removed because of tuberculosis caused by malnutrition. There was also a man who managed to survive the bombing and lived in his relative’s home, but left it later because he was accused of having seen his mother die without doing anything at the time of the bombing. He had committed theft during a time of wandering and been sent to a juvenile classification home.

Ms. Matsui herself felt miserable countless times, as well. She added, “But I was still fortunate, because I had my grandmother who had also survived that day and an uncle who helped me go to high school.”

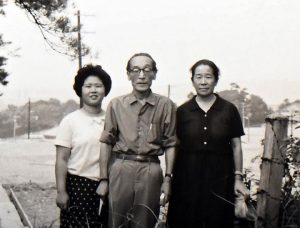

The Ayumi group had “benefactors.” They were Seiichi Nakano, professor at Hiroshima University who also served as director for “the support group for Hiroshima children,” a group collecting notes from A-bombed children, and his wife Chitose (both have already passed away). The place her group members always came together was the government’s residence in Higashisenda-machi (now part of Naka Ward) where Mr. Nakano’s family lived.

The residence was filled with a cozy atmosphere like family. Chitose always asked them “Did you eat?” A huge loaf of white bread was always in stock at their home. The couple celebrated members’ birthdays, too. They gave a novel by Pearl Buck to Ms. Matsui.

At age of 20, Ms. Matsui got a job at the present-day Hiroshima Labor Bureau. Mr. Nakano kindly visited her at workplace. He also became a guarantor for other group members when they were employed. He never abandoned anyone in the group who could not continue to work, or were caught by police. “Both Mr. and Mrs. Nakano worked hard to let us open our minds,” Ms. Matsui said.

Her group issued the newsletter “Ayumi” as a “youth team for the support group.” The group members steadily broadened the circle of mutual support by visiting a local coming-of-age ceremony to recruit new members. The membership then increased to 100.

Through Mr. Nakano, the group’s organizer, members had more opportunities to share their A-bombing experiences with others. Ms. Matsui, who was then in her 20s, also recounted her experience several times upon request from a peace group.

(Originally published on April 3, 2025)