Documenting of Hiroshima, 80 years after A-bombing: On June 27, 1965, “Kinoko-kai (Mushroom Club)” is formed

Apr. 13, 2025

Microcephalic A-bomb survivors with a strong presence

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

On June 27, 1965, people with microcephaly (those exposed to radiation from the U.S. military’s atomic bombing while in their mothers’ wombs who became intellectually and physically impaired) along with their family members, formed the “Kinoko-kai (Mushroom Club)” in Hiroshima City. The club’s name represents a wish for the strong growth of people with microcephaly by overcoming barriers like a mushroom pushing past the fallen leaves even though it grows in the shaded area.

When the club’s first meeting took place at the Women’s Center in Fujimi-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward), six in-utero A-bomb survivors with microcephaly who at the time were nearly twenty years old, attended the meeting along with their parents. The parents shared their thoughts, such as “As long as we, the parents are alive, it is possible to take care of them, but what would happen if we die?” “In a campaign to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, our children’s problem was crushed and ignored,” (according to a club’s newsletter published in 1966). They decided on three pillars of the club’s activities, which were to seek recognition by the government as an A-bomb sufferer, lifetime coverae, and abolition of nuclear weapons.

Early on, presence of A-bomb survivors with microcephaly was recognized by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC, now called the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF),” an organization established by the U.S. An article written by a pediatrician in 1952 analyzed that seven out of eleven people, who had experienced the atomic bombing within 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter in their first-half phase of the fetal period, had microcephaly along with intellectual challenges. It concluded central nervous system deficit may happen to the fetus due to radiation of the atomic bomb detonation unless effective shielding was in place for their mothers.

Meanwhile, one of the parents revealed in the meeting, “ABCC explained to me microcephaly was not caused by the atomic bombing but estimated to be attributable to malnutrition of mother’s body.” The parents felt frustrated, pointing out their children had simply provided ABCC with valuable information (according to the club’s newsletter published in 1966).

Hand-written note

Their unattended situation after the war changed through cooperation from the former ABCC staff Mikiko Yamanouchi (who died in 2020 at the age of 89.) Ms. Yamanouchi had worked for ABCC since 1955. In 1965, she was engaged in coordinating the survivors’ inspection schedule. One day, she met with the poet Munetoshi Fukagawa (who died in 2008 at the age of 87), at a coffee shop, and was asked to provide information about A-bomb survivors with microcephaly. They seemed to have known each other previously.

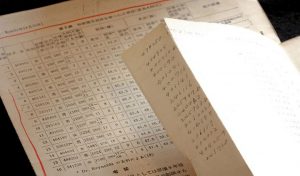

According to Naomasa Hirao, 61, secretary general of the Mushroom Club and others who had a chance to meet with Ms. Yamanouchi in her lifetime, she apparently looked up files in her organization based on identification numbers of microcephalic A-bomb survivors, which were included in a paper written by ABCC published in 1956, to find them, and transcribed their names to her note by hand. Information of the 16 survivors with microcephaly she could identify was then brought to the Hiroshima Research Group in Hiroshima, which consisted of writers and journalists, leading to formulation of the organization among people concerned and their family.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yamanouchi was a second-year student at Yamanaka Girls High School, affiliated with Hiroshima Women’s High School of Education (present-day Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School in Fukuyama). Almost all of the 360 students in their first-year and second-year at her school perished in the bombing as they were mobilized to help demolition of buildings in Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward), but she survived because she happened to return to her hometown located in present-day Etajima City the day before the bombing.

In order to feed her family, she decided to work at ABCC, the organization sometimes faced with criticism from the public like, “ABCC looks into survivors but does not treat them.” Her first daughter Izumi Haramori, now 67, and a resident of Minami Ward, said, “I guess my mother had a big inner conflict.” She once was frightened by the fear someone may have followed her after she extracted the information she was asked to provide. Ms. Haramori added, “I think my mother just tried to fulfill a mission she was given as a person who survived.”

Identified as A-bomb disease

Toshihiko Akinobu, then member of a research group and employee of RCC broadcasting (who died in 2010 at the age of 75), was also aware of the reality faced by the in-utero A-bomb survivors with microcephaly by visiting with schools and facilities. Mr. Akinobu made an appeal to the public for them with his reportage entitled “Kono sekai no katasumi de (At the corner of this world)” published the month following the birth of the Mushroom Club, which he had supported.

In 1967, the national government recognized the microcephaly of in-womb A-bomb survivors was attributable to A-bomb radiation, added it within the scope of symptoms being designated as A-bomb disease based on the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law, and paid their medical costs as a national expense. So far, 25 A-bomb survivors with microcephaly have joined the mushroom club, and ten members are still alive. Supporters have continued to provide help for them.

(Originally published on April 13, 2025)