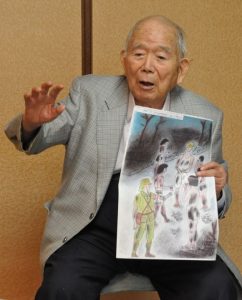

Survivors’ Stories: Keiji Harada, 95, Saeki Ward, Hiroshima City: Schoolgirls, still childlike in appearance, plead for water

Apr. 14, 2025

Burdened by a sense of guilt, unable to fulfill their request, “I could have done something.”

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Keiji Harada, 95, who wandered through Hiroshima shortly after the atomic bombing at the age of 15, was unable to fulfill the desperate pleas for water from schoolgirls, who had suffered burns. Still burdened by a deep sense of guilt, he recalled that moment in a voice tinged with emotion, “Couldn’t I have done something?”

At the time, he was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (today’s Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial High School). A week before the A-bombing, he entered a training center in the Koyaura area (now part of Saka-cho), while his family evacuated to the village of Okukaita (now the town of Kaita). His father, Mitsugu, who had been temporarily transferred to the Chugoku Regional Superintendency-General from the Hiroshima prefectural government, stayed behind at their home in Funairikawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward).

August 6 was a rest day at the training center. Mr. Harada went to the evacuation site to see his mother, Kazuko, and was asked to take a lunchbox to his father. At that moment, a flash of light appeared around him, and he recalled, “The whole earth trembled.” A cloud rose into the sky, tinged with pink.

A younger student from his neighborhood told him Hiroshima had been annihilated, and Mr. Harada rushed to search for his father. He was stopped by a military police officer on the Higashi Ohashi Bridge (now in Minami Ward). He felt something unusual at the sight of people with tousled hair, dressed in rags and tatters, walking in rows. He returned to the evacuation site for a short time, but his worry grew, and he headed back into the city.

He explained his situation to the military police officer on the Higashi Ohashi Bridge and was allowed to pass. When he reached Kako-machi (now part of Naka Ward), several schoolgirls, still childlike in appearance, emerged from the smoke. Their hair was burned, their bodies were covered in injuries, and they wore only bloodstained underwear. They pleaded, “Give us water,” so he immediately gathered empty cans, filled them with water gushing out from a water pipe, and began handing it out.

“Hey, are you trying to kill those schoolgirls?” The military police officer snapped at him. Forced to obey, he threw the water away against his will. The schoolgirls looked at him with reproach in their eyes and walked off. When he also crossed the Sumiyoshi Bridge with an aching heart, he saw countless bodies floating on the surface of the river. He remembered those schoolgirls, thinking they might have jumped into the river, desperate for water.

In his severely damaged home, someone with a swollen face was lying in the drawing room. Mr. Harada realized it was his father when he heard the voice say, “Keiji, you’ve come.” When his father asked for water, Mr. Harada hesitated at first, but this time, he brought a 1.8-liter bottle filled with water and let his father drink as much as he wanted. That night, they lay together, and later, Mr. Harada learned his father’s urine had turned black.

On August 7, Mr. Harada walked 13 kilometers to the village of Okukaita alone. When he met her mother, he burst into tears. To pick up his father, he returned home with Motoko, his elder sister by two years, pulling a two-wheeled cart. They placed their father, who was groaning in pain, on the cart and brought him back to the village.

After the war, Kazuhiko, Mr. Harada’s elder brother by five years and a student soldier, was soon demobilized and traveled to and from Hiroshima on behalf of his father.

Mr. Harada graduated from the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (today’s Hiroshima University) after the war. He worked for Hiroshima Bank and other organizations before serving as the chief director of a school corporation in Kure. During this time, he witnessed his family suffering greatly from the aftereffects of the A-bombing. The burn scars on his father’s face had become swollen, and people said he looked like a different person. His father underwent two facial surgeries and was forced to live uncomfortably with his fingers fused together. Both his elder brother and elder sister, who had entered the city after the A-bombing, developed cancer.

In 2000, Mr. Harada suffered a cerebral infarction and was hospitalized. He listened to a radio program in which the Hiroshima City government encouraged listeners to share their experiences of the A-bombing. This inspired him to begin sharing his own account as he felt a strong sense of being alive. He shared his account through painting pictures, and also became involved in compiling of video testimonies.

In February 2025, he published his account of his experience in the A-bombing and donated copies to schools. In it, he wrote about the schoolgirls and the suffering endured by his family. He calls on the United States, the country that dropped the atomic bombs, to take the lead in the world in abolishing nuclear weapons and promoting world peace, as a way of atoning for its offense.

(Originally published on April 14, 2025)