Twelve former residents of Sarugaku-cho, hypocenter area that had disappeared except for A-bomb Dome, gather for first time in 52 years to recreate their neighborhood, mourn victims, and uncover records

Jul. 6, 1997

On July 5, people involved with the area of “Sarugaku-cho,” the predecessor to what is now Ote-machi 1-chome, in Hiroshima City’s Naka Ward where the A-bomb Dome is located, came together for the first time in 52 years and decided to launch a survey to recreate the vanished neighborhood. Those A-bomb survivors, who had been unable to locate the remains of parents or siblings, never opened up to the public because the experiences they suffered were so cruel. With the idea of “leaving behind a record of the area where we were born and raised to serve as a foundation of peace,” a new grassroots initiative was launched in tribute to those who died and to uncover records of the devastation caused by the bombing.

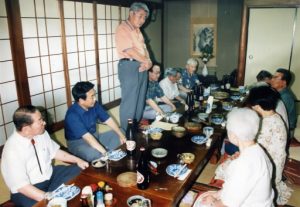

At a restaurant located south of the A-bomb Dome, 12 men and women between the ages of 55 and 78 who could be reached in the city gathered for the event. Except for three men in their 70s who were at different fields of battle at the time, the participating survivors directly experienced the bombing where they had been working as mobilized students or at sites where they had evacuated, or were exposed to A-bomb radiation when they entered the city soon after the bombing.

Eiichi Ise, 59, an organizer of the gathering who still manages a tobacco shop at Otemachi 1-chome, made opening remarks. “Our mission as people who survived is to recreate Sarugaku-cho and mourn the people who died,” said Mr. Ise. The participants, who had lost contact with each other during the chaotic period after the bombing, shared what they experienced the day of the bombing and about their life afterward when introducing themselves to the others.

Shigeo Moritomi, 67, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, said, “Due to the atomic bombing, I lost four members of my family, which ran a bedding shop with the business name ‘Tsunetomo.’” Hiroko Nagaki, 66, a resident of the city’s Saeki Ward who had lost her parents and older sister, said, “I was the second daughter of the Okamoto family, which ran a miso shop. I have lived in Hiroshima for seven years.” In response, Toshiko Kurata (née Kasai), seated next to Ms. Nagaki, said, “Your older sister ‘Fu-chan’ was my close friend.” The remains of Ms. Kurata’s father have never been found.

The participants shared their childhood memories of the area, including about how they used to swim in Motoyasu River or run around in the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the predecessor to the A-bomb Dome, as if trying to fill in the gap of 52 years. They confirmed the names and contact information for other surviving residents whose whereabouts were known to them.

According to Hiroshima City government records, 1,055 people representing 260 households lived in the Sarugaku-cho area before the war, but information on the actual number of households in the area at the time of the bombing and the number of residents who died in the bombing is mostly unclear because of forced evacuation that took place during the war. In 1965, the name Sarugaku-cho itself disappeared after the area was incorporated into the neighborhoods of Ote-machi 1-chome and Kamiya-cho 2-chome.

Those who gathered that day agreed to encourage other survivors in Sarugaku-cho to join the activities of the group “Yagura-kai,” the name of which their parents had once used because it pointed to the city’s nature as a castle town, to recreate the townscape, and to hold a memorial service on August 2 at Saiko-ji Temple, located next to the A-bomb Dome. Mr. Ise said, “We want to bring this area back to life by all means while people associated with Sarugaku-cho are still alive and well.” For more details about the group’s activities, please call 082-247-5324.

(Originally published on July 6, 1997)

At a restaurant located south of the A-bomb Dome, 12 men and women between the ages of 55 and 78 who could be reached in the city gathered for the event. Except for three men in their 70s who were at different fields of battle at the time, the participating survivors directly experienced the bombing where they had been working as mobilized students or at sites where they had evacuated, or were exposed to A-bomb radiation when they entered the city soon after the bombing.

Eiichi Ise, 59, an organizer of the gathering who still manages a tobacco shop at Otemachi 1-chome, made opening remarks. “Our mission as people who survived is to recreate Sarugaku-cho and mourn the people who died,” said Mr. Ise. The participants, who had lost contact with each other during the chaotic period after the bombing, shared what they experienced the day of the bombing and about their life afterward when introducing themselves to the others.

Shigeo Moritomi, 67, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, said, “Due to the atomic bombing, I lost four members of my family, which ran a bedding shop with the business name ‘Tsunetomo.’” Hiroko Nagaki, 66, a resident of the city’s Saeki Ward who had lost her parents and older sister, said, “I was the second daughter of the Okamoto family, which ran a miso shop. I have lived in Hiroshima for seven years.” In response, Toshiko Kurata (née Kasai), seated next to Ms. Nagaki, said, “Your older sister ‘Fu-chan’ was my close friend.” The remains of Ms. Kurata’s father have never been found.

The participants shared their childhood memories of the area, including about how they used to swim in Motoyasu River or run around in the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the predecessor to the A-bomb Dome, as if trying to fill in the gap of 52 years. They confirmed the names and contact information for other surviving residents whose whereabouts were known to them.

According to Hiroshima City government records, 1,055 people representing 260 households lived in the Sarugaku-cho area before the war, but information on the actual number of households in the area at the time of the bombing and the number of residents who died in the bombing is mostly unclear because of forced evacuation that took place during the war. In 1965, the name Sarugaku-cho itself disappeared after the area was incorporated into the neighborhoods of Ote-machi 1-chome and Kamiya-cho 2-chome.

Those who gathered that day agreed to encourage other survivors in Sarugaku-cho to join the activities of the group “Yagura-kai,” the name of which their parents had once used because it pointed to the city’s nature as a castle town, to recreate the townscape, and to hold a memorial service on August 2 at Saiko-ji Temple, located next to the A-bomb Dome. Mr. Ise said, “We want to bring this area back to life by all means while people associated with Sarugaku-cho are still alive and well.” For more details about the group’s activities, please call 082-247-5324.

(Originally published on July 6, 1997)