Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — In August 1960, campaign begins to preserve A-bomb Dome

Apr. 6, 2025

“Out of sight, out of mind”

Deaths of parents and friends in bombing should not be forgotten

by Minami Yamashita and Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writers, and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

In the summer of 1960, 15 years after the atomic bombs were dropped by the U.S. military, young students began a movement to preserve the dilapidated A-bomb Dome, located in Hiroshima City’s downtown. Their activity was inspired by the death of a young girl from leukemia in Hiroshima, a city striving to recover after the bombing. Around that period, people involved in the start of the movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs sweeping the nation were largely partisan, resulting in a severe ideological divide among campaign members about strategic direction of the movement. The global trend of expansion and proliferation of nuclear weapons continued unabated. Activities to preserve the memory of the tragedies brought about by nuclear weapons would gradually increase in significance.

Hiroshima Paper Crane Club conducted fundraising and signature-collection campaigns, amplifying support based on enthusiasm of young people

In August 1960, the time the “Hiroshima Paper Crane Club” launched its campaign to preserve the A-bomb Dome, Masahiro Mimura, 79, now a resident of Hiroshima City’s Nishi Ward, was a third-year student at Fuchu Junior High School (in the area of Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture). Along with other members of his generation, Mr. Mimura stood on the streets and loudly proclaimed, “Give us your donations and signatures. Let’s preserve the A-bomb Dome.”

Born in October 1945, Mr. Mimura was 14 years old at that time. On August 6, 1945, his father had experienced the atomic bombing near Hiroshima Station. His mother had entered Hiroshima on August 7 from their home at the time in the village of Nukushina (in the city’s present-day Higashi Ward), in an attempt to understand the whereabouts of her family and was exposed to A-bomb radiation together with her son, who was in her womb at the time. His parents were hospitalized one after the other in the spring of 1960 due to cancer.

“I joined the paper crane club because the club’s members had visited my father at the hospital,” said Mr. Mimura. Regularly visiting patients at the Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward), the club members were also there to provide encouragement to Mr. Mimura’s father, who had been hospitalized for stomach cancer and was certified as suffering from “A-bomb disease.” After Mr. Mimura’s father died in June despite everyone’s wishes for his recovery, the members attended his funeral.

Soon after, Mr. Mimura joined the club based on an invitation from Ichiro Kawamoto, an organizer of the club. Mr. Mimura was taking care of his bedridden mother at a different hospital, taking turns with his aunt staying overnight there. “During the toughest time in my life, the paper crane club provided me a place for peace of mind,” said Mr. Mimura.

The group mainly worked on activities to support A-bomb survivors who had been admitted to the Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital in ways that were possible in their role as students, such as creating flowerbeds to soothe the hospitalized patients and providing food purchased with donations of their own pocket money. At a club gathering that had been in May, the members were inspired by Hiroko Kajiyama’s diary entry about the A-bomb Dome, which was read aloud at the event.

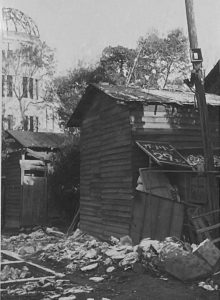

Mr. Mimura explained, “We were emotional about the issue because we were junior high-school students, but we did think the dome should be preserved.” Whenever he visited the shack in which Mr. Kawamoto was living next to the dome, the structure would come into sight. Recalling that time he said, “Back then, my impression of the dome was that it was big and frightening. There was lots of plant growth around the building, which looked to be on the verge of collapse.” Even after his mother died in November of that year, he would stand on the streets and call for preservation of the dome.

Hiroshima mayor once said, “It should break down naturally”

Around that time, Shinso Hamai, the mayor of Hiroshima City, which was responsible for management of the dome, took a passive stance about the costly preservation work, once saying, “It should break down naturally.” A brochure by the paper crane club titled Bakushinchi (in English, ‘Hypocenter’), published in 1967, indicated, “We were worried about the possibility that those who had died in the bombing could ’naturally’ be forgotten in the same way.” On the form used for the signature drive was printed the phrase “Out of sight, out of mind.”

As aims for the club, Mr. Kawamoto proposed the slogan, “Never forget the hearts of the dead” and pledged that the group would, “Not turn into a venue for the promotion of a specific political party, religion, or vocation, and never become a place for mere fun and games.” Support for the club’s earnest efforts gradually expanded.

Raised funds grew to 66 million yen

The club’s concrete efforts to preserve the A-bomb Dome began in 1964, four years after the signature drive was begun. In December of that year, 11 organizations, including the Hiroshima Prefectural Congress against A- and H-Bombs (Hiroshima Gensuikin), which had splintered into two groups, requested that the Hiroshima City government preserve the dome. In July 1966, the Hiroshima City Council unanimously passed a resolution for “permanent preservation” of the dome.

In November, the city government began a fundraising campaign to cover the costs of preservation. Mr. Hamai himself stood on the streets of Tokyo to collect donations. Later recalling that activity, Mr. Hamai said, “What deeply changed my mind into believing that the A-bomb Dome must be preserved was the earnest campaign carried out by those children,” according to the Chugoku Shimbun dated August 1, 1967. The campaign raised around 66 million yen, greatly exceeding the initial target of 40 million yen, from both Japan and overseas. With that, the first phase of preservation work was begun in April 1967.

----------------

Citizens vacillate regarding fate of dome

Differing opinions: “Keep as a memorial,” “Keep as a lesson from the war,” “Prefer not to remember the tragedy”

On April 5, 1915, the A-bomb Dome had first been constructed as the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall, based on a design by Jan Letzel, an architect from Czechoslovakia. On August 6, 1945, after the building was renamed the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Hall, the atomic bomb detonated in the sky above Shima Hospital around 160 meters southeast of the building. With the remaining structure greatly damaged, citizens were divided about whether to preserve or tear down the structure.

In October 1949, the city carried out a survey of 500 people who had experienced the atomic bombing about whether they wanted to see the dome preserved or torn down. Of 428 respondents, 62 percent expressed their “hope that the dome is preserved,” with 35 percent expressing their “hope that the dome is torn down.” Asked about the reasoning for preservation of the dome, 50.4 percent responded, “Keep as a memorial,” the largest number, followed by “Keep as lesson from the war,” selected by 40 percent of the respondents. Regarding the reason for wanting the structure torn down, 60.9 percent replied, “Prefer not to remember the tragedy.”

In the same year, the city conducted a design competition for Peace Memorial Park, indicating its aim of preserving the dome within the planned park site. A proposal from the architect Kenzo Tange’s group was selected as the prize-winner of the design competition. That plan positioned the dome as a key symbol in the park’s landscape. However, at a roundtable discussion held by the Chugoku Shimbun on August 6, 1951, Hiroshima City Mayor Shinso Hamai spoke of difficulties in protecting the structure’s remains, saying, “Preservation of the dome should not be achieved with public funds.”

In 1953, the Hiroshima Prefectural government, as owner of the dome, handed the title of the building over to the city. In 1961, an expert warned about the risk of collapse, saying, “It can no longer be left to its own devices.” The city outsourced to Shigeo Sato, an architect and professor at Hiroshima University, the work of confirming the structural integrity of the building, ultimately receiving Mr. Sato’s report that, “The dome can be preserved if reinforcement work is carried out.” With that, Mr. Hamai expressed his intent to proactively consider preservation.

What Mr. Sato proposed for reinforcement was a new method of injecting epoxy resin, a state-of-the-art material at that time, into the dome’s brick walls. The method made reinforcement possible without altering the appearance of the dome, which had been largely destroyed, and was adopted for use in the first phase of preservation.

-------

Split in movement to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs

Conflict among factions broke out over U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, Soviet nuclear testing

Hidankyo’s activities temporarily “paused”

“We call on people around the world to further promote the movement to ban atomic and hydrogen weapons by transcending differences in political parties, religious sects, and social systems.” That was the message announced as the declaration of the World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held for the first time in Hiroshima in August 1955. Led by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo), the world conference was held the next year and every year thereafter, but the movement began to fracture into different groups due to factional conflicts.

It all started with negotiations to revise the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which got started in 1958. The government’s negotiations surrounding the revised treaty revealed momentum toward acceptance of the establishment of U.S. military bases in Japan, as was the case in the previous treaty, and clarification of the U.S. defense obligations to Japan. Gensuikyo reacted strongly, arguing, “This is a dangerous move that attempts to place Japan in the position of becoming involved in the crisis of a nuclear war on its own.” The organization adopted a stance of “blocking the treaty revision.”

The Hiroshima Prefecture political establishment also reacted. The prefectural government had originally set aside a 300,000-yen subsidy for the Gensuikyo world conference, scheduled to take place in Hiroshima in August 1959, in its supplementary budget proposal submitted at the regular session of the Hiroshima Prefectural Assembly, held in June of the same year. However, assembly members belonging to the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the national ruling party, questioned the subsidy, saying, “The conference has deviated from its original purpose by its aim of nullification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.” Other assembly members affiliated with the Socialist Party of Japan supported the subsidy proposal, but the assembly ultimately passed by majority vote a revised proposal that did not include the subsidy.

Following the prefectural assembly decision, other such assemblies, including the Hiroshima City Council, also decided they would not send their delegations to the conference and other measures. After the revised security treaty between the United States and Japan was signed in January 1960, the Democratic Socialist Party and other organizations that had kept their distance from Gensuikyo formed the National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons (present-day KAKKIN) in 1961. With participation from LDP policymakers and others, the council began to hold conferences independently.

The next major trigger for the split was a conflict in opinions about nuclear testing being conducted by the Soviet Union. That country had resumed the testing of nuclear weapons in 1961 after a temporary pause, going so far as conducting a test when the World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen bombs was being held in 1962. During the Cold War between East and West, intense debate developed over whether to oppose nuclear tests by “any country” and whether the United States' defensive stance could be treated in the same light. Those affiliated with the Socialist Party of Japan and other parties demanded that the conference submit a letter of protest to the Soviet Union, but lacking support from other factions including the Communist Party, that group left the conference.

Gensuikyo, falling into dysfunction, left management of the World Conference held in Hiroshima City in 1963 to the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Hiroshima Gensuikyo). On August 5, 1963, Ichiro Moritaki, chair of Hiroshima Gensuikyo, said, “We cannot help but scream out that we are against any sort of nuclear test conducted by any nation.” However, after the battle among the different factions to mobilize affiliated participants in an attempt to gain advantage at the convention, those affiliated with the Socialist Party of Japan and the others left the conference venue. The following day, they held their own conference at a different venue.

Gensuikyo chapters in the three prefectures of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Shizuoka formed a three-prefectural liaison council of A- and H-bomb damages in March 1964. Based on that move, the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs (Gensuikin) was established in February 1965.

The aftermath of the conflict also affected A-bomb survivor groups. The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), which had originally participated in Gensuikyo, dropped out of the organization. Around 1965, Gensuikyo’s activities had fallen “dormant,” according to a 50-year history of Gensuikyo. For example, the group no longer held general assemblies or engaged in other activities. Since 1964 in Hiroshima, two different groups have shared the same name “Hiroshima Prefectural Hidankyo.”

---------------

Ceaseless nuclear tests: “First” tests conducted by France and China, ”megaton-class” test by Soviet Union

Some anti-nuclear supporters in Hiroshima called for “white paper” to convey reality of disaster

In the 1960s, a trend persisted whereby nuclear arsenals were expanded and strengthened, accompanied by nuclear testing. As of 1960, according to a survey conducted by a group called the Federation of American Scientists, the United States possessed 18,638 nuclear warheads, followed by the Soviet Union with 1,627, and the United Kingdom with 105. That year, France carried out its first nuclear test.

In October 1961, the Soviet Union conducted a “megaton-class nuclear test,” according to the Chugoku Shimbun dated at that time, which reported the test to be of the most powerful nuclear weapon on earth at “50 megatons,” equivalent to more than 3,000 times the destructive force of the atomic bomb used on Hiroshima. In October 1962, one year later, tension escalated between the nuclear superpower United States and the Soviet Union because of the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The situation escalated to the brink of nuclear war.

In 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), which came into effect in October of that year. Amid growing international criticism of the “ashes of death” (radioactive fallout) generated by nuclear testing, the PTBT banned, excluding underground tests, nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, in space, and in the sea. France, however, did not join the treaty, as it lagged behind in nuclear weapons development. China, which also resisted joining the treaty, conducted its first nuclear test in 1964. The United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom continued to conduct their own underground nuclear tests.

Around the same time, in Hiroshima, academia and cultural elites were urging Japan’s national government to publish a “white paper on damages caused by atomic and hydrogen bombs” and to announce the details of the paper through the United Nations with the aim of communicating the reality of the horror of the atomic bombings to the world. Despite the fact that nearly 20 years had passed since the atomic bombings, there had been no comprehensive surveys conducted by the government on the damages wrought by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, including the death toll.

"Have the atomic bombs come to be known for their power, or for their human tragedy?" asked Toshihiro Kanai, an editorial writer for the Chugoku Shimbun at the time, when he raised “the issue of submitting a white paper on damages caused by atomic and hydrogen bombs” at a subcommittee meeting of the three-prefectural liaison council of A- and H-bomb damages in August 1984. In his request for the white paper, he proclaimed that “the document could play a key role in a nationwide and undivided peace movement.”

Highlights of A-bomb Dome preservation

August 1945

The U.S. military drops the atomic bombs. Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (present-day A-bomb Dome), located very close to the hypocenter in Hiroshima City, is largely destroyed.

August 1949

The proposal submitted by Kenzo Tange’s group is selected as the winner of the design competition for Hiroshima City’s Peace Memorial Park. The concept of utilizing the dome as a symbol of the park is finalized.

October 1949

The Hiroshima City government conducts a survey of 500 A-bomb survivors inquiring about whether or not the dome should be preserved or torn down.

November 1953

Hiroshima Prefectural government transfers the title of the dome to the city government.

April 1960

Hiroko Kajiyama dies at age of 16, leaving a diary, which includes an entry about the A-bomb Dome.

August 1960

Hiroshima Paper Crane Club begins a fundraising and a signature-collection campaign.

December 1964

Eleven peace organizations call on the city government to preserve the dome.

July 1965

The city government conducts a survey on the structural integrity of the dome.

July 1966

Hiroshima City Council unanimously decides on “permanent preservation of the dome.”

November 1966

Hiroshima City government begins fundraising for preservation of the dome.

April through August 1967

The city government conducts the first phase of preservation work on the dome.

(Originally published on April 6, 2025)