Sarugaku-cho, neighborhood around A-bomb Dome, Part 3: “Bocchan,” former high school baseball player who loved children

Jul. 27, 1997

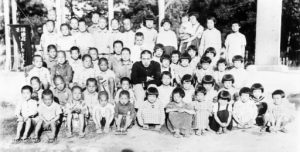

Children with close-cropped or bobbed hair are all lined up surrounding a broad-shouldered young man. Next to the group in the photograph appears a flag that reads, “Sarugaku-cho Nishi-gumi Children’s Club Meeting.” The back of the photo is stamped with the date “June 5, 1944.”

Gazing at the photo, Hiroyuki Imada, 64, the photo owner who lives in Hiroshima’s City’s Naka Ward, explained that, “It was taken at Gokoku Shrine on the West Military Drill Ground, located on the north side of Sarugaku-cho. The man was Mr. Iwasaki. He took good care of us.”

Taught music and organized hikes for children

The man was known in the neighborhood by the nickname “Bocchan.” Even during the war, he would gather children together and teach them songs, take and hand out commemorative photos, and organize what would now be called hikes. “He was tall and slender and taught me how to swim in the Motoyasu River in front of the A-bomb Dome,” said Etsuko Ibayashi (née Fujii), 62, a resident of Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward who was one of the children in the photo, as if speaking of something that happened yesterday.

The second child to the left of the young man is Tsuneo Kasai, 63, who lives in the city’s Saeki Ward. He said he remembered listening to LPs at Bocchan’s house, which had the feel of a traditional home.

“That was the first time I learned about Bach and Beethoven and the last time I listened to their music,” Mr. Kasai smiled wryly. “I helped his family evacuate to the village of Midorii (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward) using a large, two-wheeled handcart. But I have not seen him since the war ended. He might have died.”

The man’s home, located at 44 Sarugaku-cho, less than 100 meters east of the A-bomb Dome, stretched from the streetcar street in front of the present-day Hiroshima Municipal Baseball Stadium to the street one block south. There were stone steps at the entrance facing the streetcar street, which had once served as a moat, retaining the charm of a castle town following construction of Hiroshima Castle.

As these reporters searched for the young man’s whereabouts with the photo in hand, we found that he had belonged to the baseball team of Hiroshima Commercial High School, a team that had achieved a nationwide reputation since before the war. Turning the pages of a publication on high school baseball history, we found his name among the players who had competed in the National High School Baseball Invitational Tournament in 1936. The record of his participation reads, “Ryotaro Iwasaki: First baseman. One hit in four at-bats.” Takeshi Maruyama, 77, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, and one of the few surviving teammates who was also a classmate of Mr. Iwasaki, remembered him clearly.

“He was the tallest in our grade at 186 centimeters, and I was the next tallest,” Mr. Maruyama said, adding that Mr. Iwasaki’s nickname was “utility pole.” He had gone on to Keio University after graduating from high school. Mr. Maruyama heard that he had died in the atomic bombing. What happened to the man with the “pleasant personality” of Mr. Maruyama’s recollection and to his family? A clue to the thread of his life, which had once again broken off, was found in Sarugaku-cho.

We were ultimately able to reach Mr. Iwasaki’s younger sister, now 76, the only family member still alive, through a former resident of Sarugaku-cho who knew a relative of Mr. Iwasaki.

Kind older brother, 26 at the time

Despite her poor health, his sister responded, “My brother fled our home to the Chamber of Commerce building with Mr. Hirata, our next-door neighbor, saying to Mr. Hirata, ‘I want you to tell them I’m here.’ He was 26 years old. Mr. Hirata also suffered greatly, and then...,” she said, her voice trailing off.

Ryotaro Iwasaki had always admired Motoharu Haiyama, older than Mr. Iwasaki in school and the team pitcher who won the Summer Koshien Tournament. He entered the same university, Keio, as Mr. Haiyama but had to return home due to a respiratory disease. While helping his parents manage their camera shop, he would look after children in the neighborhood.

The remains of his father, Kakuji, 54 at the time of the bombing, have also never been found. Eisuke, 57, an uncle who lived with the family and served as president of the neighborhood association, and Sadami, 53, Eisuke’s wife, made it to the village of Midorii, which they had determined as their site of evacuation, but they both died around the same time. Ryotaro’s record collection had been reduced to a pile of ashes in the ruins of his family’s storehouse.

“Even today, I think of my kind brother, who had been awaiting help, every time I pass by the Chamber of Commerce. It’s not that I’ve forgotten; it’s simply that I don’t want to be reminded of that time. I’m truly sorry.”

The younger sister of the former high school baseball player spoke faintly as she hung up the telephone.

(Originally published on July 27, 1997)

Gazing at the photo, Hiroyuki Imada, 64, the photo owner who lives in Hiroshima’s City’s Naka Ward, explained that, “It was taken at Gokoku Shrine on the West Military Drill Ground, located on the north side of Sarugaku-cho. The man was Mr. Iwasaki. He took good care of us.”

Taught music and organized hikes for children

The man was known in the neighborhood by the nickname “Bocchan.” Even during the war, he would gather children together and teach them songs, take and hand out commemorative photos, and organize what would now be called hikes. “He was tall and slender and taught me how to swim in the Motoyasu River in front of the A-bomb Dome,” said Etsuko Ibayashi (née Fujii), 62, a resident of Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward who was one of the children in the photo, as if speaking of something that happened yesterday.

The second child to the left of the young man is Tsuneo Kasai, 63, who lives in the city’s Saeki Ward. He said he remembered listening to LPs at Bocchan’s house, which had the feel of a traditional home.

“That was the first time I learned about Bach and Beethoven and the last time I listened to their music,” Mr. Kasai smiled wryly. “I helped his family evacuate to the village of Midorii (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward) using a large, two-wheeled handcart. But I have not seen him since the war ended. He might have died.”

The man’s home, located at 44 Sarugaku-cho, less than 100 meters east of the A-bomb Dome, stretched from the streetcar street in front of the present-day Hiroshima Municipal Baseball Stadium to the street one block south. There were stone steps at the entrance facing the streetcar street, which had once served as a moat, retaining the charm of a castle town following construction of Hiroshima Castle.

As these reporters searched for the young man’s whereabouts with the photo in hand, we found that he had belonged to the baseball team of Hiroshima Commercial High School, a team that had achieved a nationwide reputation since before the war. Turning the pages of a publication on high school baseball history, we found his name among the players who had competed in the National High School Baseball Invitational Tournament in 1936. The record of his participation reads, “Ryotaro Iwasaki: First baseman. One hit in four at-bats.” Takeshi Maruyama, 77, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, and one of the few surviving teammates who was also a classmate of Mr. Iwasaki, remembered him clearly.

“He was the tallest in our grade at 186 centimeters, and I was the next tallest,” Mr. Maruyama said, adding that Mr. Iwasaki’s nickname was “utility pole.” He had gone on to Keio University after graduating from high school. Mr. Maruyama heard that he had died in the atomic bombing. What happened to the man with the “pleasant personality” of Mr. Maruyama’s recollection and to his family? A clue to the thread of his life, which had once again broken off, was found in Sarugaku-cho.

We were ultimately able to reach Mr. Iwasaki’s younger sister, now 76, the only family member still alive, through a former resident of Sarugaku-cho who knew a relative of Mr. Iwasaki.

Kind older brother, 26 at the time

Despite her poor health, his sister responded, “My brother fled our home to the Chamber of Commerce building with Mr. Hirata, our next-door neighbor, saying to Mr. Hirata, ‘I want you to tell them I’m here.’ He was 26 years old. Mr. Hirata also suffered greatly, and then...,” she said, her voice trailing off.

Ryotaro Iwasaki had always admired Motoharu Haiyama, older than Mr. Iwasaki in school and the team pitcher who won the Summer Koshien Tournament. He entered the same university, Keio, as Mr. Haiyama but had to return home due to a respiratory disease. While helping his parents manage their camera shop, he would look after children in the neighborhood.

The remains of his father, Kakuji, 54 at the time of the bombing, have also never been found. Eisuke, 57, an uncle who lived with the family and served as president of the neighborhood association, and Sadami, 53, Eisuke’s wife, made it to the village of Midorii, which they had determined as their site of evacuation, but they both died around the same time. Ryotaro’s record collection had been reduced to a pile of ashes in the ruins of his family’s storehouse.

“Even today, I think of my kind brother, who had been awaiting help, every time I pass by the Chamber of Commerce. It’s not that I’ve forgotten; it’s simply that I don’t want to be reminded of that time. I’m truly sorry.”

The younger sister of the former high school baseball player spoke faintly as she hung up the telephone.

(Originally published on July 27, 1997)