Sarugaku-cho, neighborhood around A-bomb Dome, Part 9: Full picture of A-bomb damage still unclear, leaving questions about identity of remains

Aug. 3, 1997

In its quest to visit people involved in the area of Sarugaku-cho, a neighborhood that disappeared in the atomic bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun met Hiroko Nagaki, 66, a resident of Hiroshima City’s Saeki Ward who was first identified as an “A-bomb victim” despite still being alive. Her maiden name and status at the time of the bombing — “Hiroko Okamoto (female student)” — were contained in the “list of remains” laid to rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound in Peace Memorial Park for which the Hiroshima City government is continuing to seek out relatives or other contacts. After Ms. Nagaki herself contacted the city, it was found that the identity of the remains had been mistaken. With that, starting last year, her name was deleted from the list of remains.

Ms. Nagaki said, “Even if I had been mistaken for my older sister, I myself was the one that had picked up her remains after her death. I wonder why my name was listed, although I know there is no way to find out the reason.” She was 14 at the time of the atomic bombing and a third-year student at Yamanaka Girls’ High School.

Alumni directory also indicated she “passed away”

Her family managed the Mikai miso production and wholesale business at the address of “40 Sarugaku-cho,” located on the east side of the present-day A-bomb Dome. Of her family of four, her parents and older sister were killed in the atomic bombing. At the time of the bombing, her father, Hideo, then 42, was out doing work related to air defense, and her mother, Ei, was engaged in building-demolition work. Her older sister, Fusako, 18 at the time and a fifth-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School, had returned home from the Hiro Air Base in Kure because she had been feeling unwell.

Ms. Nagaki said, “I had been mobilized as a student to work at the Mitsubishi shipyard (around 4.3 kilometers from the hypocenter).” On the following day, she managed to make it to the village of Midorii (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward), an area in the suburbs that had been designated to serve as an evacuation site for residents of Sarugaku-cho. Arriving a moment too late, she cut the braids of the hair of her sister, who had already drawn her last breath, and cremated her body by the riverbank. Then, on August 22, when her mother died after being brought to an evacuation site in Asakita Ward, Ms. Nagaki dressed her mother’s body in a burial kimono with help from a woman she knew and cremated the body herself. Her father’s whereabouts were unknown.

She said, “I was around the age where I could have screamed and cried. And I had been suffering from a high fever. I find myself wondering how was I able to do it.” In September, as the chaos after the bombing continued, she was taken in by a relative in Kagawa Prefecture. After graduating from a girls’ high school there, she married. Her husband worked for a travel agency, so the family relocated several times. The alumni directory of Fukuromachi Elementary School, her alma mater, also identified her as having “passed away.” A former friend of hers discovered the error, leading to the alumni directory being corrected around 10 years ago.

Bewilderment about finding identical name as mother

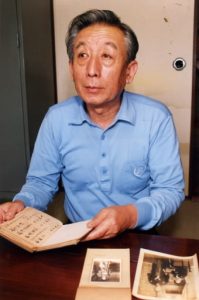

“In my case, a name identical to that of my mother is listed. It appears we are being told that the remains in our family grave are not hers,” said Yoshiyuki Mikami, 63, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward. Mr. Mikami feels bewildered and a bit concerned about the list of A-bomb victim remains released by the Hiroshima City government every summer.

In the family register of deaths placed at the Buddhist altar at his home, five family members are indicated as having, “Died in the atomic bombing.” Those victims were Mr. Mikami’s grandmother, Tame, 75 at the time; mother, Asako, 38; second brother, Masato, 12; and younger brother, Masao, two years old at the time. All family members who were in the area of “Aburaya-cho,” located around 500 meters from the hypocenter, perished after they had moved there because their original home at the address of “17 Sarugaku-cho” had been designated for demolition. In place of his father, who was serving in the military, and Mr. Mikami himself, who was a sixth-grade elementary school student at the time and had been evacuated to a relative’s home, his mother’s younger sister went to their home to look for the family.

Mr. Mikami added, “I was told my mother had died carrying Masao on her back in a coat for carrying babies inside a water tank at our home.” Because his aunt remembered seeing the pattern on the coat worn by Asako, she identified and cremated their bodies and placed the remains in a grave. “But more than around 10 years ago, since a relative informed me that the name on the list might not be my mother’s, I have felt uneasy,” said Mr. Mikami.

The city’s list of victims’ remains carries the name “Asako Mikami.” He said, “Considering my aunt, who searched for my mother’s remains right after the atomic bombing, I have no option but to think the list happens to include someone with the same name as that of my mother. Even so, it’s a thought that doesn’t help anyone.”

It has been confirmed that 112 residents of Sarugaku-cho had died in the atomic bombing by the end of 1945. The remains of many of those victims have not been recovered. For bereaved family members who were able to bury the remains in their family graves, they say they believe the remains to be “probably the right ones,” as if trying to convince themselves.

(Originally published on August 3, 1997)

Ms. Nagaki said, “Even if I had been mistaken for my older sister, I myself was the one that had picked up her remains after her death. I wonder why my name was listed, although I know there is no way to find out the reason.” She was 14 at the time of the atomic bombing and a third-year student at Yamanaka Girls’ High School.

Alumni directory also indicated she “passed away”

Her family managed the Mikai miso production and wholesale business at the address of “40 Sarugaku-cho,” located on the east side of the present-day A-bomb Dome. Of her family of four, her parents and older sister were killed in the atomic bombing. At the time of the bombing, her father, Hideo, then 42, was out doing work related to air defense, and her mother, Ei, was engaged in building-demolition work. Her older sister, Fusako, 18 at the time and a fifth-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School, had returned home from the Hiro Air Base in Kure because she had been feeling unwell.

Ms. Nagaki said, “I had been mobilized as a student to work at the Mitsubishi shipyard (around 4.3 kilometers from the hypocenter).” On the following day, she managed to make it to the village of Midorii (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward), an area in the suburbs that had been designated to serve as an evacuation site for residents of Sarugaku-cho. Arriving a moment too late, she cut the braids of the hair of her sister, who had already drawn her last breath, and cremated her body by the riverbank. Then, on August 22, when her mother died after being brought to an evacuation site in Asakita Ward, Ms. Nagaki dressed her mother’s body in a burial kimono with help from a woman she knew and cremated the body herself. Her father’s whereabouts were unknown.

She said, “I was around the age where I could have screamed and cried. And I had been suffering from a high fever. I find myself wondering how was I able to do it.” In September, as the chaos after the bombing continued, she was taken in by a relative in Kagawa Prefecture. After graduating from a girls’ high school there, she married. Her husband worked for a travel agency, so the family relocated several times. The alumni directory of Fukuromachi Elementary School, her alma mater, also identified her as having “passed away.” A former friend of hers discovered the error, leading to the alumni directory being corrected around 10 years ago.

Bewilderment about finding identical name as mother

“In my case, a name identical to that of my mother is listed. It appears we are being told that the remains in our family grave are not hers,” said Yoshiyuki Mikami, 63, a resident of Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward. Mr. Mikami feels bewildered and a bit concerned about the list of A-bomb victim remains released by the Hiroshima City government every summer.

In the family register of deaths placed at the Buddhist altar at his home, five family members are indicated as having, “Died in the atomic bombing.” Those victims were Mr. Mikami’s grandmother, Tame, 75 at the time; mother, Asako, 38; second brother, Masato, 12; and younger brother, Masao, two years old at the time. All family members who were in the area of “Aburaya-cho,” located around 500 meters from the hypocenter, perished after they had moved there because their original home at the address of “17 Sarugaku-cho” had been designated for demolition. In place of his father, who was serving in the military, and Mr. Mikami himself, who was a sixth-grade elementary school student at the time and had been evacuated to a relative’s home, his mother’s younger sister went to their home to look for the family.

Mr. Mikami added, “I was told my mother had died carrying Masao on her back in a coat for carrying babies inside a water tank at our home.” Because his aunt remembered seeing the pattern on the coat worn by Asako, she identified and cremated their bodies and placed the remains in a grave. “But more than around 10 years ago, since a relative informed me that the name on the list might not be my mother’s, I have felt uneasy,” said Mr. Mikami.

The city’s list of victims’ remains carries the name “Asako Mikami.” He said, “Considering my aunt, who searched for my mother’s remains right after the atomic bombing, I have no option but to think the list happens to include someone with the same name as that of my mother. Even so, it’s a thought that doesn’t help anyone.”

It has been confirmed that 112 residents of Sarugaku-cho had died in the atomic bombing by the end of 1945. The remains of many of those victims have not been recovered. For bereaved family members who were able to bury the remains in their family graves, they say they believe the remains to be “probably the right ones,” as if trying to convince themselves.

(Originally published on August 3, 1997)