Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In May 1978, A-bomb survivor demands “No More” at UN Special Session on Disarmament

May 1, 2025

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

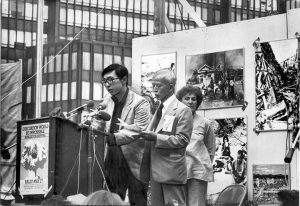

On May 27, 1978, a citizens’ rally calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons took place in New York City, where the Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly Devoted to Disarmament was being held. Around 15,000 people from 11 countries, including the United States and Canada, gathered at Hammarskjöld Square, in front of the United Nations Headquarters, which featured an exhibit of photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombings and folded paper cranes. An A-bomb survivor from Hiroshima stood to speak on behalf of the participants from Japan.

The speaker was Masuto Higaki, 82 at the time, who served as co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) and secretary-general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo; chaired by Ichiro Moritaki). He talked about the experience of losing his wife and their three-year-old child in the atomic bombing and declared, “We are faced with a choice between the survival of humanity or its annihilation. No More Hiroshima, No More Nagasaki.”

Mr. Higaki had been a participant in the A-bomb survivors’ movement from its earliest days, contributing to the formation of a local A-bomb sufferers association in Hiroshima’s Kaita-cho area, among other work. He was the most senior member of the delegation to the United Nations numbering around 500 people.

In an interview before leaving for the United States, he had said, “This is my last contribution. I will risk my life on this once-in-lifetime chance,” as was reported in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper on May 8. At the rally, he pointed out how A-bomb survivors “even today, continue to suffer from the effects of radiation.” In response to his call for “No More,” the venue erupted with a chant of “Peace.”

Another member of the delegation was Busuke Shimoe, a resident of Fuchu City who died in 1996 at the age of 92. Mr. Shimoe had participated in the A-bomb survivors’ movement from its inception. He lost his wife, Tefu, 40 at the time of the bombing, who had been trapped under their collapsed house in the area of Hakushimakuken-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) and, six days after the bombing, their fifth daughter, Takako, who had been born the previous year.

Tattered clothes

Mr. Shimoe had himself been severely wounded in the bombing and taken to the same hospital with his wife and daughter. From his hospital room, he could see white smoke rising from the area where corpses were being incinerated. He held on to the determination that, “Such atrocities should never be allowed to happen to humankind anywhere in the world,” as written in Genbaku (in English, ‘Atomic Bombing’), a collection of personal accounts published by an association of A-bomb sufferers in Fuchu City in 1982.

When he visited the United States, the nation that had dropped the atomic bombs, Mr. Shimoe brought along with him the tattered clothes he had been wearing when he experienced the bombing near his home. At an exhibit of A-bomb photographs held in the lobby of the UN Headquarters, he showed local children the keloid scars that remained on his wrists and other areas, communicating the incurable nature of the wounds he had suffered. The Romanian ambassador who saw the clothing remarked how he had been unable to stop his own trembling, as reported in the Chugoku Shimbun dated June 22, 1978.

Mr. Shimoe’s second daughter, Ikue Mitsunari, 89, a resident of Fukuyama City, and his third daughter, Nobuko Nakayama, 87, a resident of Fuchu City, who had been evacuated to present-day Fuchu City at the time of the atomic bombing, both remarked, “He was a gentle father, but when it came to the abolition of nuclear weapons, he was dedicated to doing whatever he had to do.”

Confrontation at conference

While the calls from the A-bomb survivors elicited sympathy among people outside the venue, confrontation over nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation continued within the special session meeting. A proposal to establish the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty, which had been a demand of Japan and other nations, met with resistance from China and France, two nuclear weapons states. A proposal to designate August 6 as “Disarmament Day” was opposed by European and other nations, likely in a reflection of the stance of the United States.

Ultimately, after the meeting timeframe was extended by two days, four final documents were adopted on June 30. The Geneva Disarmament Committee, which had been led by the United States and the Soviet Union, was reorganized, and an agreement to pave the way for participation of other nuclear weapons states such as France was reached. A decision was also made to designate the week beginning October 24, which marked the timing of the UN Charter entering into force in 1945, as “Disarmament Week.”

However, some aspects of the final documents had been watered down, due in part to the lack of concrete measures for the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, a situation the Chugoku Shimbun reported about on July 1. The number of nuclear warheads around the world continued to increase, reaching a peak of around 70,000 in 1986.

The First Special Session on Disarmament did not provide an opportunity for A-bomb survivors to speak. However, at the Second Special Session, held in 1982, Senji Yamaguchi, a Nagasaki A-bomb survivor who died in 2013 at the age of 82, took to the stage. Mr. Yamaguchi spoke while holding up a photo of his own keloid scars and concluded with the words, “No More War, No More Hibakusha.”

(Originally published on May 1, 2025)

On May 27, 1978, a citizens’ rally calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons took place in New York City, where the Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly Devoted to Disarmament was being held. Around 15,000 people from 11 countries, including the United States and Canada, gathered at Hammarskjöld Square, in front of the United Nations Headquarters, which featured an exhibit of photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombings and folded paper cranes. An A-bomb survivor from Hiroshima stood to speak on behalf of the participants from Japan.

The speaker was Masuto Higaki, 82 at the time, who served as co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) and secretary-general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo; chaired by Ichiro Moritaki). He talked about the experience of losing his wife and their three-year-old child in the atomic bombing and declared, “We are faced with a choice between the survival of humanity or its annihilation. No More Hiroshima, No More Nagasaki.”

Mr. Higaki had been a participant in the A-bomb survivors’ movement from its earliest days, contributing to the formation of a local A-bomb sufferers association in Hiroshima’s Kaita-cho area, among other work. He was the most senior member of the delegation to the United Nations numbering around 500 people.

In an interview before leaving for the United States, he had said, “This is my last contribution. I will risk my life on this once-in-lifetime chance,” as was reported in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper on May 8. At the rally, he pointed out how A-bomb survivors “even today, continue to suffer from the effects of radiation.” In response to his call for “No More,” the venue erupted with a chant of “Peace.”

Another member of the delegation was Busuke Shimoe, a resident of Fuchu City who died in 1996 at the age of 92. Mr. Shimoe had participated in the A-bomb survivors’ movement from its inception. He lost his wife, Tefu, 40 at the time of the bombing, who had been trapped under their collapsed house in the area of Hakushimakuken-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) and, six days after the bombing, their fifth daughter, Takako, who had been born the previous year.

Tattered clothes

Mr. Shimoe had himself been severely wounded in the bombing and taken to the same hospital with his wife and daughter. From his hospital room, he could see white smoke rising from the area where corpses were being incinerated. He held on to the determination that, “Such atrocities should never be allowed to happen to humankind anywhere in the world,” as written in Genbaku (in English, ‘Atomic Bombing’), a collection of personal accounts published by an association of A-bomb sufferers in Fuchu City in 1982.

When he visited the United States, the nation that had dropped the atomic bombs, Mr. Shimoe brought along with him the tattered clothes he had been wearing when he experienced the bombing near his home. At an exhibit of A-bomb photographs held in the lobby of the UN Headquarters, he showed local children the keloid scars that remained on his wrists and other areas, communicating the incurable nature of the wounds he had suffered. The Romanian ambassador who saw the clothing remarked how he had been unable to stop his own trembling, as reported in the Chugoku Shimbun dated June 22, 1978.

Mr. Shimoe’s second daughter, Ikue Mitsunari, 89, a resident of Fukuyama City, and his third daughter, Nobuko Nakayama, 87, a resident of Fuchu City, who had been evacuated to present-day Fuchu City at the time of the atomic bombing, both remarked, “He was a gentle father, but when it came to the abolition of nuclear weapons, he was dedicated to doing whatever he had to do.”

Confrontation at conference

While the calls from the A-bomb survivors elicited sympathy among people outside the venue, confrontation over nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation continued within the special session meeting. A proposal to establish the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty, which had been a demand of Japan and other nations, met with resistance from China and France, two nuclear weapons states. A proposal to designate August 6 as “Disarmament Day” was opposed by European and other nations, likely in a reflection of the stance of the United States.

Ultimately, after the meeting timeframe was extended by two days, four final documents were adopted on June 30. The Geneva Disarmament Committee, which had been led by the United States and the Soviet Union, was reorganized, and an agreement to pave the way for participation of other nuclear weapons states such as France was reached. A decision was also made to designate the week beginning October 24, which marked the timing of the UN Charter entering into force in 1945, as “Disarmament Week.”

However, some aspects of the final documents had been watered down, due in part to the lack of concrete measures for the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, a situation the Chugoku Shimbun reported about on July 1. The number of nuclear warheads around the world continued to increase, reaching a peak of around 70,000 in 1986.

The First Special Session on Disarmament did not provide an opportunity for A-bomb survivors to speak. However, at the Second Special Session, held in 1982, Senji Yamaguchi, a Nagasaki A-bomb survivor who died in 2013 at the age of 82, took to the stage. Mr. Yamaguchi spoke while holding up a photo of his own keloid scars and concluded with the words, “No More War, No More Hibakusha.”

(Originally published on May 1, 2025)