Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after the A-bombing: August 6, 1986, peace ambassadors in Canada

May 11, 2025

Ms. Thurlow’s proposal came to fruition

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

On August 6, 1986, Toronto, Canada resident and atomic bomb survivor Setsuko Thurlow, who was 54 at the time and is now 93, attended the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony with two local high school students. They were peace ambassadors, sent by the Toronto Board of Education, where she worked, following her proposal to help establish disarmament and peace education.

“I break the silence”

When Ms. Thurlow was a second-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School), she was exposed to the atomic bombing at the site where she had been mobilized to work as a student. The loss of her relatives, including her elder sister, her 4-year-old nephew, and her friends left a deep impression on her as a formative experience. After graduating from Hiroshima Jogakuin University, she went to the United States to continue her studies. Later, after getting married, she moved to Toronto.

She said, “People in Toronto were too silent on nuclear issues. Breaking that silence was the focus of my efforts.” Starting in 1970, she poured her energy into the anti-nuclear movement while working as a social worker for the city’s Board of Education.

Ms. Thurlow, along with more than 300 people, published an opinion ad in a newspaper, calling for the complete abolition of nuclear weapons. In 1975, marking the 30th anniversary of the A-bombing, she held an exhibition at Toronto City Hall, featuring materials such photos of the A-bombing provided by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Starting the following year, she began holding an annual gathering on August 6.

A-bomb survivors gave her emotional support

The presence of A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima gave her emotional support. While attending Nagarekawa Church as a student, she assisted Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto with his activities, including the “moral adoption campaign,” in which American citizens sent money to support the lives of A-bomb orphans. During her student years, she met Ichiro Moritaki, who was leading the A-bomb survivors’ movement, for the first time, and she also came into contact with the poet Sadako Kurihara, who was exposed to the A-bomb.

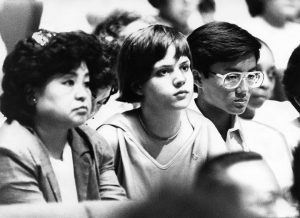

She wanted young people to experience the A-bombed site firsthand and proposed the establishment of a peace ambassador program. She collected essays and projects on the significance of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from students at 100 high schools across Toronto, and selected the top two students: David Lin and Karen Goodfellow, both 17 years old. When they arrived in Hiroshima on July 31, 1986, they listened to the testimony of an A-bomb survivor and interacted with young people. After returning to Canada, they held report sessions at senior high schools and community meetings.

Their energetic activities caught the attention of then-Prime Minister Martin Brian Mulroney, and they were invited to the Prime Minister’s Office. Ms. Goodfellow brought a thousand paper cranes as a symbol of her call for the abolition of nuclear weapons, which was reported by local media. Ms. Thurlow said, “Their actions helped shift the mindset not only of youth but also members of the board of education. Awareness of nuclear issues was raised throughout the region.”

However, promoting such activities in Canada was difficult, as Canada was closely aligned with the U.S., the nuclear superpower that had dropped the A-bombs, and to make matters worse, it was during the Cold War. When Ms. Thurlow was invited to the exhibition of paintings depicting A-bombing held in the capital city of Ottawa, a bomb threat was made against the art museum.

Moreover, when Ms. Thurlow was traveling to the U.S. to attend the United Nations Special Session on Disarmament, she was stopped at immigration. She felt the pressure from the U.S. side, and reflecting on the experience, she said, “The U.S. didn’t want to admit people who advocated against nuclear weapons. It was the first time I had experienced such blatant and malicious behavior that I shed tears.”

On the other hand, she thought, “Canada is a multi-ethnic country, and some people have relatives who suffered under the Japanese army. I need to acknowledge the history of harm caused, so that those people can open their hearts.” She continued to share her experience of the A-bombing both at home and abroad. In 2007, when she turned 75, she became involved with the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), a non-governmental organization founded primarily by anti-nuclear doctors in Austria.

(Originally published on May 11, 2025)