Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In October 1978, Motomachi redevelopment project completed

May 2, 2025

From shacks to high-rise apartment buildings

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

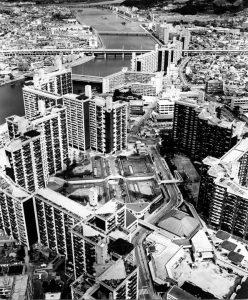

In October 1978, a ceremony marking the completion of a redevelopment project was held at Central Park in Hiroshima City’s Motomachi district (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). In an area near the east bank of Honkawa River, where a cluster of shacks had remained after the war, high-rise apartment buildings totaling 4,566 units, along with a park, were established. A monument unveiled during the ceremony, which was attended by the prefectural governor, the city mayor, and local residents, carried an inscription reading, “Hiroshima’s postwar era will never end without improvements to this district.”

Provisional housing totals 1,800 units

The Motomachi district, where numerous military facilities had been built one after another since the Meiji era in Japan (1868–1912), was devastated in the atomic bombing by the U.S. military on August 6, 1945. Shortly after the bombing, housing-supply corporations affiliated with the government and the Hiroshima Prefectural and City governments began building provisional housing units on the ruins of the Motomachi district for the many citizens who had lost their homes in the central part of the city. Approximately 1,800 units had been constructed over the course of around two years.

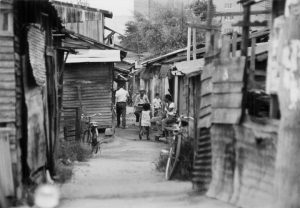

Despite that, a housing shortage persisted. People with nowhere to go—due to the atomic bombing, repatriation from the war abroad, or evictions due to construction of roads and parks—had erected shacks for living on public land, such as greenbelts on the riverbanks in the area. This provisional housing was particularly conspicuous on the east bank of the Honkawa River.

A survey initiated by the prefectural and city governments in October 1968 identified a total of 2,600 “substandard housing units” in the riverside and other areas in the Motomachi district, comprising 2,951 households of 8,694 people. Of that total, 1,065 households were located along the river, with 955 of the households including A-bomb survivors as family members.

In the Motomachi district, even after dilapidated public housing had been replaced with municipal and prefectural mid-rise, reinforced-concrete apartment buildings, some clusters of the shack-like housing remained. The Honkawa River’s east riverbank had been dubbed the “A-bomb slum,” with the media also using such language in their reporting.

Sumiko Yamamoto, 88, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, moved her family of four from the area of Yokogawa (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward) into a shack in the Motomachi district in the 1960s. She opened a café to earn money for medical treatment for her oldest son, Mitsuharu, 63, a resident of Naka Ward who was suffering from tuberculosis. Although she lacked experience in the restaurant industry, she did have experience in business following her father’s death in the atomic bombing. “I would work hard day and night,” said Ms. Yamamoto. Her restaurant flourished based on the patronage of company workers in the local area.

She rented a shack, renovated by her carpenter husband, from an acquaintance. Mitsuharu recalled, “Cats would sometimes fall through the holes that would often appear in the ceilings. The different housing units were built so close together we could even hear quarrels between married couples living a few doors away.” Some of the housing units shared kitchens and toilets, resulting in close interactions among neighbors.

Meanwhile, according to the Motomachi District Redevelopment Project Commemorative Journal, published in 1979, fires broke out in the district almost every year between 1961 and 1976. In July 1967, 149 shacks clustered in the riverside area were burned to the ground.

Delays become apparent

Although housing erected illegally in many areas was being demolished, delays in the reconstruction of the Motomachi district grew ever more apparent, prompting the prefectural and city governments to initiate their own redevelopment project. In 1969, full-scale construction began on a complex of high-rise apartment buildings, some of which rose as high as 20 stories. According to the previously mentioned commemorative journal, 2,600 dilapidated housing units were demolished. The journal also indicated that during the construction, the remains of people presumed to have died in the atomic bomb were also unearthed. Approximately 22.6 billion yen was spent on housing construction and other projects, with around 3.2 billion yen spent on the establishment of related facilities. An elementary school and a kindergarten were also built.

People who had been evicted from their homes gradually moved into the high-rise apartment buildings. Ms. Yamamoto’s family was among them. Walking paths and gardens were built on the roofs. “Our building had a modern feel, and I was happy to be able to live there,” said Ms. Yamamoto, who continued to run her café in the shopping center built in the center of the apartment complex.

(Originally published on May 2, 2025)