Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In November 1976, Hiroshima and Nagasaki mayors pay visit to United States

Apr. 27, 2025

Call for abolition of nuclear weapons at United Nations

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On November 25, 1976, Hiroshima City Mayor Takeshi Araki and Nagasaki City Mayor Yoshitake Morotani arrived in the United States together. The purpose of their visit was to meet with then United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim and others at the UN Headquarters in New York, with the aim of raising awareness about the devastation caused by the atomic bombings and calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. That was the first time the mayors of the A-bombed cities had engaged in advocacy activities at the UN Headquarters.

Before departing, Mr. Araki paid a visit to the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and attended a ceremony marking his departure at Hiroshima Station. In front of around 500 city officials and city council members, he said with determination, “Sincerely conveying the feelings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I will urge the United Nations to take effective measures to abolish nuclear weapons.”

In 1975, 30 years after the atomic bombings, Hiroshima and Nagasaki had formed a sister-city relationship and begun planning a joint visit to the United Nations as a step in conveying to the world the horrific nature of nuclear weapons. With cooperation from Genichi Akatani, Japan’s first UN Assistant Secretary-General, who had served in that position since 1972, the mayors were able to meet with UN Secretary-General Waldheim.

Photographs of devastation

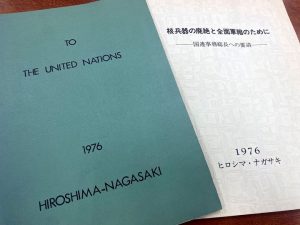

Prior to the visit, the two cities had formed a committee of 12 experts and prepared a petition document titled “For the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons and Complete Disarmament.” The petition, which called for an end to nuclear testing and a ban on the use of nuclear weapons, detailed the reality of the atomic bombings as ‘a lesson from human history.’ The petition also included many photographs depicting the devastation after the atomic bombings.

After verification of the death toll from the atomic bombings by the end of December 1945, the petition detailed the number of estimated deaths at around 140,000 (with a margin of error ±10,000) people in Hiroshima and around 70,000 (±10,000) in Nagasaki. Based on microscopic images of pathological specimens that had been returned from the United States in 1973 and data on the incidence of leukemia and other cancers as well as other such information, the petition delved into the acute effects and late effects from A-bomb radiation. The petition also reported that many A-bomb survivors continued to suffer from the aftereffects of radiation.

Other people besides the two mayors also joined the delegation, including Goro Ouchi, an A-bomb survivor who was serving as president of the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association. After making requests of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency within the U.S. Department of State, the group met with UN Secretary-General Waldheim on December 1. It was reported that when the petition, written in English, had been handed over to the UN Secretary-General, Mr. Waldheim conveyed that he sympathized with the A-bomb survivors because their suffering was shared by all humankind and that the United Nations would work to mobilize the conscience of the world to continue similar efforts as those engaged in by the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

At a press conference after the meeting, Hiroshima Mayor Araki and his group said, “Until now, there has been a sense of futility in the fact that the voices of both cities, in the form of conveying the reality of the atomic bombings and protesting against nuclear testing, have not yet resonated around the world.” Emphasizing the effectiveness of the direct appeal to the United Nations, he added, “Now, we believe our cities’ call has been understood.” The Japanese delegations stayed until November 9, meeting with Hamilton Amerasinghe (from Sri Lanka), President of the United Nations General Assembly, as well as the ambassadors to the United Nations from 12 countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union.

Gap emerges

However, a gap between the delegations and the nuclear weapons states gradually emerged. France’s senior advisor, on behalf of the country’s ambassador to the United Nations, justified its possession of nuclear weapons by explaining that the nation did not wish to become captive to any country that would threaten France with nuclear weapons, regardless of the country. China did not respond to a request to meet with the Japanese delegations.

According to data compiled by the Federation of American Scientists, the total of number of nuclear weapons existing worldwide in 1976 reached 48,993 warheads, the majority of which were in the possession of the United States and the Soviet Union. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which had come into force in 1970, mandated that negotiations take place on nuclear disarmament, while still permitting the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, and China to maintain possession of their nuclear weapons stockpiles, but no progress had been made on negotiations. On December 21, 1976, shortly after the mayors’ visit to the United Nations, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution calling for a United Nations Special Session on Disarmament to be held in 1978.

In 1976, after its ratification of the NPT, Japan’s national government made the decision to send Foreign Minister Sunao Sonoda to a special session of the UN General Assembly in order to call for “nuclear disarmament with the ultimate aim of the abolition of nuclear weapons,” citing Prime Minister Takeo Miki’s address to Japan’s parliamentary Diet that year in September that “ours stands alone as the only nation to have suffered a nuclear attack.” However, behind the government’s assertion of being “the only nation,” there were people negatively impacted by the atomic bombings who had been abandoned and deprived of aid.

(Originally published on April 27, 2025)