Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — In November 1995, Hiroshima and Nagasaki mayors deliver statements at ICJ

May 18, 2025

“Starting point should be the thoughts and feelings of those who died under the mushroom cloud”

Led to ICJ advisory opinion: “Use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law”

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer, and Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

On November 7, 1995, the mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki cities stood in a courtroom to present their statements at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, the Netherlands. The ICJ, one of the key organizations of the United Nations, is also called the “World Court.” Regarding the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons, the issue on which the ICJ was deliberating, the mayors explained the tragedy of the atomic bombings as well as radiation’s effects, asserting that the bombings were a “violation of international law.” Meanwhile, nuclear-armed nations argued that the use of nuclear weapons would be lawful depending on the situation. In its advisory opinion released the following year, in 1996, the ICJ ruled that the threat or use of nuclear weapons “would generally be contrary to the rules of international law,” but avoided drawing a conclusion on whether it would be lawful or unlawful in extreme circumstances in which the very survival of a state is at stake. The ICJ opinion would lead to a movement calling for an explicit legal ban on nuclear weapons but left room for nuclear powers to continue their justification of use of the weapons.

Reality of atomic bombings presented at court, with support from attorneys-at-law

In early August 1995, Takeya Sasaki, 55 at the time, an attorney with an office in Hiroshima City’s Naka Ward who is now 84, held discussions in Hiroshima with other attorneys from Japan and overseas to promote what was called the “Word Court Project,” aimed at the elimination of nuclear weapons. The attorneys debated whether any nation was available to request the ICJ to allow statements to be made by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki mayors. Ahead of the upcoming oral statements to be presented by each nation later in the fall of that year, there appeared to be no opportunity for the mayors to speak.

Looking back on that time, Mr. Sasaki said, “We believed it was imperative for the court to understand the tragic reality of the atomic bombings when reaching its judgment.” He had been five years old at the time of the atomic bombing. At the time, he was in present-day Higashihiroshima City, located around 30 kilometers from the hypocenter, and thus was spared direct experience in the bombing. However, he clearly remembered seeing the back of his uncle after he had been brought back home, burned from thermal rays generated by the atomic bombing with red flesh exposed.

The Japan Confederation of A-and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) and other groups joined the project. A signature drive to claim that the use of the atomic bombs violated international law was led by the Japan Consumers’ Cooperative Union. Meanwhile, the United States and Russia were opposed to the United Nations resolution requesting the ICJ to render an advisory opinion on the threat or use of nuclear weapons. It was inevitable that the claim of illegality of the use of nuclear weapons would be opposed by some.

Representative from Nauru approached

To convey the reality of the atomic bombings toward a judgment that the use of nuclear weapons had been unlawful, Mr. Sasaki and Kazushi Kaneko, then chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo) who died in 2015 at the age of 89, visited the ICJ in May 1995 with a book containing photographs of the atomic bombings and survivors’ testimonies. After their return to Japan, Japan’s national government was asked to submit an application to the ICJ for Hiroshima City Mayor Takashi Hiraoka and Nagasaki City Mayor Iccho Ito to serve as counsels to the government and provide their testimony at the World Court.

But the government refused to address the request. Since the end of the war, Japan had called for protection under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” on national security grounds without declaring the use of nuclear weapons, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to be illegal.

As a result of their discussions, Mr. Sasaki and other members of the project came up with the idea that Nauru, an island nation located in the Pacific Ocean that opposed nuclear testing conducted by France, could apply for the mayors to provide their testimony, obtaining agreement for the idea from the Nauru representative. In September, when the campaigners sought cooperation from Mr. Hiraoka and made an effort to lobby the Japanese government once again, the government announced it had submitted an application to the ICJ for the two mayors. Mr. Sasaki said, “I assume the government thought it would lose face if the application came from another nation.”

Mention made of Sadako’s story

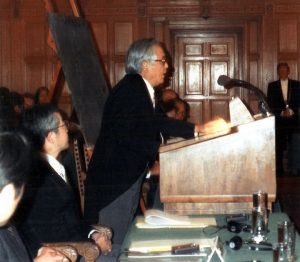

On November 7, the two mayors made their statements as counsels to the government. Some A-bomb survivors, including Senji Yamamoto, co-chair of the Nihon Hidankyo organization, also rushed to World Court. Mr. Hiraoka spoke of the victims in Hiroshima, including Sadako Sasaki, who had died of leukemia at the age of 12 ten years after the atomic bombing, declaring that both the threat and use of nuclear weapons to be “in violation of international law.” Mr. Ito, holding up a photo of the charred body of a boy who had experienced the atomic bombing in Nagasaki, emphasized the illegality of the use of nuclear weapons.

ICJ President Mohammed Bedjaoui listened to the statements made by the two mayors and described them as “impressive.” Meanwhile, Japan’s national government cautioned, “The statements were delivered independently from the government’s stance.” While not clearly expressing the use of nuclear weapons to be illegal, Japan’s government did state their use “is inconsistent with the spirit of humanity which provides international law with its philosophical foundation.”

Fifteen of a total of 22 nations that made oral statements at the World Court took the position that the use of nuclear weapons was unlawful under any circumstance. The United States and France declared use to be lawful depending on the situation, arguing that the use of nuclear weapons limited to military targets should be considered, asserting the need for nuclear deterrence policies.

The ICJ advisory opinion on the issue was issued the following year, on July 8, 1996. Given nuclear weapons’ indiscriminate nature and the radiation effects that result from their use, the opinion stated that the threat or use of nuclear weapons “would generally be contrary to the rules of international law.” However, the opinion left some ambiguity, stating that the World Court could not conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in extreme circumstances of self-defense, in which the very survival of a state is at stake.

A-bomb survivors, who had demanded that the ICJ conclude the threat or use of nuclear weapons to be illegal in any circumstances, voiced disappointment at the decision. “The opinion could be interpreted to mean that it would be possible to use nuclear weapons for certain reasons,” was one aspect of their reasoning, “The ICJ avoided making any judgment.” While Mr. Sasaki held similar dissatisfaction, he also felt that “it was sufficiently significant.” The opinion also noted the obligation to “conclude” nuclear disarmament negotiations, leaving a foothold for subsequent moves to seek an explicit legal ban on nuclear weapons.

--------------------

“Suffering from radiation effects on human beings continues today”

Mr. Hiraoka described damages

Takashi Hiraoka, 97, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, delivered an oral statement at the ICJ as Hiroshima City mayor. Mr. Hiraoka conveyed the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons based on “the reality of human suffering” caused by the atomic bombings. Looking back on that time, he said, “I am not an A-bomb survivor myself, but I wanted to deliver my statement in a way that was personal rather than framed as someone else’s issue.”

In the statement, he said, “I cannot forget an elderly woman who worked in my office with many scars remaining on her face and hands.” He then read out at the World Court a part of the personal account of A-bombing experiences written by that woman, Futaba Kitayama, who had survived being burned in the atomic bombing, an account that was introduced in this feature series published on February 16, 2025.

Parts of Ms. Kitayama’s account that Mr. Hiraoka read at that time included the passages, “When I wiped my face, I was shocked because I felt the skin on my face peeling off,” and “The skin of my five fingers also peeled off and hung dangling from my hands.” After Ms. Kitayama lost her husband in the atomic bombing, she worked for the archive department of the Chugoku Shimbun at the time when Mr. Hiraoka was serving as a staff writer for the newspaper.

The mayor also talked about the death in the atomic bombing of his cousin, a first-year student at a girls’ school who he had thought of as his own younger sister. He said, “It was almost unbearable for me to hear the lamentations of my aunt, who said, ‘If not for the war … if there had never been an atomic bombing…’”

He also spoke of other dead victims, such as many North and South Koreans, exchange students from China and other Asian nations, and U.S. prisoners of war. Referring to the existence of survivors with microcephaly (a condition marked by small head size) who had experienced the atomic bombing in their mothers’ womb and had suffered from cognitive and physical disabilities, as well as to the increased leukemia and cancer incidence among A-bomb survivors, he emphasized the persistent effects from radiation even after half a century by that time.

“Nuclear weapons are crueler and more inhumane than other weapons whose use has been prohibited by international laws to this point in time,” argued Mr. Hiraoka. He recommended that, “Through the conclusion of a treaty clearly stipulating the elimination of nuclear weapons, the world would be able to step toward a promising future.”

Portions of Mr. Hiraoka’s ICJ statement

• By placing as the starting point the wishes of those severely burned, begging for water as they suffered, and dying under the huge mushroom cloud from the atomic bombing, we must think about the nuclear era and the relationship between nuclear weapons and human beings.

•Clearly, the use of nuclear weapons violates international law, as the weapons indiscriminately killed huge numbers of non-combatants and continue to inflict suffering from radiation effects on humans to this day. The development, possession, and testing of nuclear weapons also violate international law due to the powerful threats they pose to non-nuclear nations.

• The strategy that assumes a nuclear war can be controlled and the idea of winning such a war based on the nuclear deterrence theory are a showcase for the deterioration of human intellect not equipped to imagine the consequences of nuclear war in the form of human suffering and destruction of the global environment.

--------------------

Final decision determined by president’s vote after voting deadlocked

At that time, the ICJ consisted of 14 judges, including five from nuclear-weapons states. The judges unanimously agreed that the threat or use of nuclear weapons must be compatible with the principles and rules of “international humanitarian law” applicable in armed conflicts. In the advisory opinion, the focus was on whether there was consensus on the issue of compatibility.

International humanitarian law stipulates the protection of civilians and places restrictions on the methods and means of warfare. The ICJ advisory opinion affirmed the cardinal principle that use of weapons incapable of distinguishing between civilian and military targets and causing “unnecessary suffering” was prohibited. In light of the unique damages inflicted by nuclear weapons, the opinion stated that the use of such weapons appeared to be barely reconcilable with laws applicable in armed conflict.

Meanwhile, the court considered the right of national self-defense. It did not provide a conclusion on whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in cases of national survival.

Based on that, the opinion concluded that the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be illegal, but the vote had been evenly split, seven to seven. The opinion was secured because ICJ President Bedjaoui had cast the deciding vote in favor.

All of the judges released their individual opinions. ICJ President Bedjaoui called nuclear weapons “the ultimate evil” and argued that the existence of nuclear weapons was a major challenge to humanitarian law, referring to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as well as the indiscriminate slaughter and long-term effects on humans caused by the nuclear weapons. As for the part of the advisory opinion that did not lead to a conclusion, Mr. Bedjaoui emphasized it should not be interpreted as leaving the door open for recognition of the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons.

Overall, the assertions from the judges that the threat or use of nuclear weapons was illegal stood out. Among the seven judges who opposed the opinion that the threat or use of the weapons ”would generally be contrary to the rules of international law,” three were of the opinion that it should be clearly stated that nuclear weapons are “illegal under any circumstance,” in their demand for a more powerful statement.

Of the four other judges, Stephen M. Schwebel from the United States argued that the nuclear deterrence policy of nuclear nations was a long-standing practice for self-defense and accepted by allies, and that the threat or use of nuclear weapons underlying such policy was legal. He asserted that certain nuclear attacks such as on submarines could distinguish military from civilian targets, forming the argument that the use of nuclear weapons would be legal under certain conditions.

Judges from the United Kingdom and France echoed the view of the U.S. judge. The judge from Japan indicated its perspective that the ICJ was not required to release an advisory opinion in the first place.

All 14 judges unanimously agreed on the opinion that there exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament based on Article VI of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Portions of the ICJ advisory opinion

• The threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law. However, in view of the current state of international law and of the elements of the facts at its disposal, the court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in extreme circumstances of self-defense, in which the very survival of a state is at stake.

• There exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations aimed at comprehensive nuclear disarmament under strict and effective international controls.

--------------------

Momentum gained for negotiation of TPNW, but room left for interpretation of “legality” of nuclear weapons’ use

In October 1996, three months after the advisory opinion issued by the ICJ, non-nuclear nations such as Malaysia proposed a resolution calling on the United Nations General Assembly to commence negotiations for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Although the advisory opinion lacked legal binding force, those nations sought comprehensive prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons including possession and development of the weapons with the driving force being the ICJ opinion, which deemed that the threat or use of nuclear weapons was generally illegal and concluded that there existed an obligation to bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament.

However, concrete action did not gain momentum until the 2010s. The impetus for the accelerated pace was a statement issued by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), an organization known as a watchdog for international humanitarian law that worked to extend aid and relief to disputed areas from a standpoint of neutrality. In 2010, Jakob Kellenberger, then ICRC president, took the ICJ advisory opinion one step further and asserted that the ICRC found it difficult to envisage how any use of nuclear weapons could be compatible with the rules of international humanitarian law.

Non-nuclear nations such as Austria focused on the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons and worked to enhance the efforts being made to realize the establishment of the TPNW, with support from such non-governmental organizations as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) and Nihon Hidankyo. In July 2017, at a meeting of the United Nations, the TPNW was adopted with 122 non-nuclear nations/regions voting in favor. Mexico and many other nations claiming nuclear weapons to be illegal at the ICJ deliberations also joined the treaty, which came into force in 2021.

Meanwhile, the nuclear powers and other nations protected under the “nuclear umbrella,” including Japan, have not joined the TPNW. As the ICJ advisory opinion refrained from drawing a conclusion on whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful in “extreme circumstances” related to national self-defense, that became one of the reasons for nuclear-armed nations to justify their threat or use of nuclear weapons.

After its invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia once again claimed it would not hesitate to use nuclear weapon in cases of “threats to its sovereignty.” The United States issued the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) the same year, which stated it would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners. Its stance that nuclear weapons can be lawfully used has not changed since the ICJ deliberations.

(Originally published on May 18, 2025)