Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: In February 1973, remains stored at Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

Apr. 22, 2025

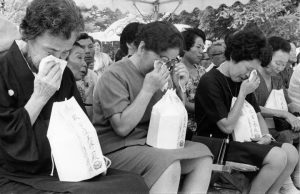

Search for bereaved family members results in remains being returned one after another

by Michio Shimotaka, Staff Writer

On February 6, 1973, the morning edition of the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper ran a headline that read, “Remains of daughter killed in A-bombing return.” The remains of a young girl stored at the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, located in Peace Memorial Park (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), had been identified based on her name and returned to her 72-year-old mother. On August 6, 1945, the girl had experienced the atomic bombing while engaged in building-demolition work, with her family never being able to locate her.

The morning edition of the Chugoku Shimbun dated February 24, 1973, carried the headline, “Found again 28 years after the atomic bombing,” and the morning edition on May 12, “Back into family’s arms after 28 years.” That year, the remains of victims with known names but who had still been unclaimed by bereaved family were identified and returned to their families one after another. Each time a return was reported, Toshiko Saiki, a “housewife” who died in 2017 at the age of 97 working to track bereaved family members, was introduced.

After the United States military had dropped the atomic bombs, Ms. Saiki moved to the village of Tomo (in Hiroshima’s present-day Asaminami Ward) to live with relatives. From the village she traveled to the city center for days on end in search of her family. Despite witnessing many people seeking help on the streets, she was unable to do anything for them, a situation she would come to regret. She herself had lost 13 relatives in the atomic bombing.

After the present-day Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound was established in 1955 in an effort centered on the Hiroshima City government, Ms. Saiki started weeding and cleaning the monument on her own initiative. She ultimately learned that the remains of her own relatives were stored there, which was also known as the “Genbaku Nokotsu Anchisho” (in English, ‘Resting place for the remains of A-bomb victims). In 1969, after hearing the name of her mother-in-law on a radio broadcast that involved the reading of names of identified remains for which bereaved family members were being sought, she went and received her remains. The following year, she saw her father-in-law’s name on a list at the Memorial Mound and received his remains as well.

In her book titled Jusannin no Shi wo Mitsumete (‘Looking at the deaths of 13 relatives’), published in 1972, Ms. Saiki described the feelings that had welled up in her heart. “As someone who knows that tens of thousands of people are still waiting inside the Memorial Mound ... even more, I would like to somehow inform those who are unaware of that fact so they can at least understand the feelings of the deceased,” wrote Ms. Saiki.

Comparing with a list

Around 1973, the names of nearly 1,900 people were known of all the remains that had been placed in the Memorial Mound. In 1968, Hiroshima City began to publicize lists of names of those victims at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, but its basic stance was to wait for requests from bereaved family members. Meanwhile, Ms. Saiki would borrow lists of bereaved family names from schools and other organizations and compare them with the lists of names of the remains stored at the Memorial Mound. When she found a match, she would send letters to the bereaved family members.

Her efforts prompted the city to take a more active approach, according to statements made by key officials in the city government in June 1973. They began comparing lists at the Memorial Mound with the registers stored within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and, by the end of July, they were able to hand over the remains of 31 identified victims to bereaved family members. In 1984, city officials asked public facilities and organizations in Hiroshima to post the lists of the names of those whose remains were stored at the Memorial Mound and, since 1984, the city has sent the lists to local governments nationwide.

Sharing her experiences with students

Ms. Saiki visited the Memorial Mound for a period of more than 40 years, continuing to clean the monument while raising awareness of its existence. Motoo Nakagawa, 66, a representative of the citizens group Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee and a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward who interviewed Ms. Saiki while she was alive, said, “I heard she shared her A-bomb experiences in front of the Memorial Mound up to seven times a day. She always spoke in a loud voice and with all her might.”

Nunose Elementary School, located in Matsubara City, Osaka Prefecture, has continued to organize school trips to Hiroshima and hold memorial services in front of the Memorial Mound for more than 40 years. That event began after school teachers had heard from Ms. Saiki about her story in 1980. One of the teachers, Tomoko Nakajima, 68, a resident of Habikino City, Osaka Prefecture, said, “Ms. Saiki’s way of life taught me that what we do is important.” Two songs inspired by Ms. Saiki’s story and the encounter with her, including one titled “A-bombed Hiroshima has no age,” are still sung at the school’s memorial services.

As of today, around 70,000 unidentified remains are considered to still be stored at the Memorial Mound. Although 813 names of that number are known, no bereaved family members have yet been found.

(Originally published on April 22, 2025)