Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: October 25, 1955, death of Sadako Sasaki

Mar. 19, 2025

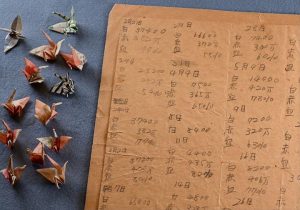

Record of blood tests, paper cranes remain

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

On October 25, 1955, Sadako Sasaki died of leukemia at the age of 12 while hospitalized at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward). With her family members by her side, she is said to have wanted to eat rice porridge with hot tea poured over it. When she was fed the dish, she said, “It’s delicious.” Those were her last words.

Eight months earlier, with Sadako in the sixth grade at Noboricho Elementary School (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), she was diagnosed with leukemia at the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC; now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, or RERF). She was two years old when she experienced the atomic bombing at her home in the area of Kusunoki-cho (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward), around 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was not injured in the bombing and grew up in good health. She was so good at sports that she posted good results in track relay races. But in the winter when she was in the sixth grade, she noticed a swelling on her neck and complained of feeling unwell.

Tomiko Kawano, 82, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, was in the same class as Sadako starting in the second grade. Ms. Kawano remembers seeing Sadako leave school with her father, Shigeo, who had come to pick her up. “She looked back repeatedly at us with a forlorn expression,” she said. Sadako was admitted to the Red Cross Hospital on February 21.

Handwritten record

Despite her classmates hearing from their homeroom teacher that the atomic bombing “seemed to be the cause” of her illness, Sadako herself was never told she had “A-bomb disease.” Nevertheless, a handwritten record she kept of her blood-test results from the time she was first hospitalized is held at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. On a piece of B5-sized, rough writing paper, she recorded the counts of her own “Red” (red blood cells), “White” (white blood cells), and “Blood” (hemoglobin) in small writing.

Because Sadako’s parents managed a barbershop, she used to often look after her younger sister and brother. While she was in the hospital, she was liked by the other children there. Kiyo Okura, two years older than Sadako who died in 2008 at the age of 67, shared a hospital room with her. In Omoide no Sadako (in English, “Memories of Sadako,” published in 2005, she wrote, “Laughter could always be heard around her.”

However, when a young girl she was acquainted with died of leukemia in July, she reportedly said, “Am I going to die like that, too?” Ms. Okura instinctively hugged Sadako’s shoulders. “Her shoulders, wrapped in a lightweight traditional yukata kimono, were thinner and bonier than I had imagined, a feeling I can’t forget to this day.”

After folded paper cranes sent by high school students in Nagoya City as well-wishes to patients in the hospital arrived at the beginning of August, Sadako began folding cranes herself. She collected used wrapping paper from gifts that had been sent to the hospital’s patients, cutting it up to use as origami paper. She continued folding cranes with Ms. Okura even after lights in the room had been turned off for the night, folding 1,000 cranes in less than one month.

When Ms. Kawano visited her in August, Sadako talked while folding paper cranes and hiding the spots on her hands and feet with her bed cover. Ms. Kawano said, “It was heartbreaking when she asked me about the happenings at junior high school.” That was the last time they saw each other. The Chugoku Shimbun dated October 26, 1955, carried a short article on Sadako’s death, including a physician’s comment about how she had died from “A-bomb disease.”

Children’s Peace Monument

While Sadako was hospitalized, her classmates formed a so-called “solidarity association” and continued to visit her even after they entered Noboricho Junior High School. However, as their school lives became busier, their visits became less frequent, a situation they later regretted. Their desire to “do something for Sadako” led to the establishment of the Children’s Peace Monument.

Sadako’s mother, Fujiko, published a memorial collection titled Kokeshi (a traditional wooden Japanese doll) in 1956. She wrote about how she had tried to support her daughter’s fight against her disease with “the greatest love” she could provide, although their family budget “was so stretched so tight our daily lives were precarious.” She expressed her inconsolable grief and gratitude to Sadako’s classmates.

(Originally published on March 19, 2025)