Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 – In March 1978, Japan’s Supreme Court hands down ruling in “Son Jin Doo case”

Apr. 30, 2025

“Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law incorporates principle of national compensation”

Trial opened door for provision of aid and relief to A-bomb survivors living overseas

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer, and Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

On March 30, 1978, the Supreme Court of Japan handed down its ruling in favor of the plaintiff in a trial in which South Korean A-bomb survivor Son Jin Doo demanded he be issued documentation known as the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. The ruling highlighted the notion that the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law “incorporates the principle of national compensation.” The court’s ruling challenged the stance adopted by the Japanese government — which separated aid and relief measures for A-bomb survivors from war responsibility — by insisting that laws involving “social security” were designed for all members of Japanese society. Citizens who considered Japan’s historical responsibility in the annexation of the Korean Peninsula supported Mr. Son’s claim, and the subsequent ruling opened the doors for the provision of aid and relief to overseas A-bomb survivors, on whom the government had turned its back.

Start was article on Korean illegal entrant who demanded “medical treatment in Japan”

On December 8, 1970, the Chugoku Shimbun carried an article in the newspaper by the wire service Kyodo News originating from the area of Saga. The article reported that one of 15 crew members aboard a South Korean vessel and arrested at a fishing port as they tried to enter Japan illegally had announced, “I secretly boarded the ship to receive medical treatment in Japan because I experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.”

Takashi Hiraoka, 97, a resident of Hiroshima City’s Nishi Ward who was serving as associate editor for the Chugoku Shimbun at the time, immediately made up his mind to pursue the story. “The article was coincidentally carried on the date commemorating the start of the Pacific Theater of World War II. I found the news when I was looking for related articles and thought I had to look into it,” said Mr. Hiraoka. Previously, in 1965, Mr. Hiraoka had been the first to report on the hardships faced by Korean A-bomb survivors living in South Korea.

During the year-end holidays in 1970, he and acquaintances with an interest in the issue paid a visit to the city of Saga’s police department, where Mr. Son was being detained. They met with Son Jin Doo, the man appearing in the article who ultimately died in 2014. At first, Mr. Hiraoka wondered to himself about “how much of Mr. Son’s story I should believe.” But he later found someone in Hiroshima who claimed he had known Mr. Son when he lived in the area of Minamikanon-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Nishi Ward), his address at the time of the atomic bombing, and corroborated the authenticity of Mr. Son’s statements. Meanwhile, the trial involving Mr. Son for the crime of violating Japan’s Immigration Control Order was fast approaching.

“Anger against injustice”

Mr. Hiraoka said, “I felt anger against the injustice of it all.” When students in Hiroshima with an interest in issues related to the atomic bombings took the lead and formed a citizens’ group in support of Mr. Son, Mr. Hiraoka joined the group’s activities on his own time. Tatsumi Nakajima, a journalist in Tokyo who died in 2008, and Rui Ito, a civic activist in Fukuoka who died in 1996, joined the group’s activities, leading to the establishment of a national-level aid and relief organization.

“Will you continue to deliberately ignore him?” was a slogan used in one of the citizens’ group’s flyers. The group distributed flyers and called for “bail and provision of medical treatment” for Mr. Son. Given the historical background of Korean A-bomb survivors, who had traveled to Japan to escape poverty or were forced into labor since the time of Japan’s annexation of Korea and then experienced the atomic bombings, the group members emphasized Japan’s responsibility for such people.

Mr. Son was sentenced to serve 10 months at a prison in Fukuoka, but the enforcement of his sentence was stayed due to his tuberculosis and suspected A-bomb disease. He was hospitalized in Fukuoka Prefecture, where he applied for issuance of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate with cooperation from his supporters. In July 1972, the Fukuoka Prefectural government rejected his application based on national government guidelines. He filed a lawsuit with the Fukuoka District Court seeking to overturn the rejection of his application.

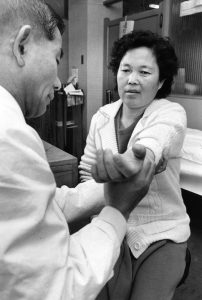

In January 1973, receiving support from Hiroshima citizens, Mr. Son was transferred to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward), where he was able to undergo examination by a physician engaged in medical care for A-bomb survivors. Mr. Son called attention to the dire situation faced by A-bomb survivors living in South Korea, saying, “In my home country, there are other A-bomb survivors who live lives of hardship, including my own family,” as was reported in an article appearing in the Chugoku Shimbun at that time. Mr. Son was diagnosed with a low white blood cell count.

Meanwhile, support for Mr. Son from local A-bomb survivors’ associations and other organizations did not grow as much as expected. The citizens’ group continued working to collect donations to cover trial expenses. Mr. Hiraoka wrote articles in other media as well to support that cause. Three young attorneys served as representatives on behalf of Mr. Son, exploring legal principles to fight his case, which lacked case precedent.

Yasufumi Kubota, 79, one of the attorneys who played a key role, was 26 years old at the time of the lawsuit. Mr. Kubota had become an attorney in Tokyo in 1970 after graduating from the University of Tokyo. He was asked to help in the case by supporters of Mr. Son who he had met through an immigration issue he was particularly interested in. It is thought that there were few attorneys familiar with administrative law related to Mr. Son’s case because that type of law was an elective subject in the bar exam. “I initially wanted to be a bureaucrat, so I had thoroughly set about studying administrative law,” said Mr. Kubota.

“National moral duty” noted

One point of contention was the legal nature of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law. The Fukuoka Prefectural government, the case defendant responsible for carrying out administrative work related to certificate issuance under delegation from the national government, asserted that the medical relief law was a “social security law” aiming at promotion of the health and welfare of members of Japanese society and hence was not applicable to illegal entrants. The plaintiffs in the case argued that the medical relief law represented “national compensation law” for the provision of relief to all those who had experienced the atomic bombings, without discrimination based on nationality or place of residence, as a responsibility for the results of the war Japan itself had waged.

The attorney Mr. Kubota said, “What greatly contributed to the ruling was the fact that there was no nationality requirement in the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law.” The brief submitted to the court detailed “Japan’s national responsibility vis-à-vis the Korean people” and included a description about how A-bomb survivor demands for national compensation helped motivate the national government to establish the law, given the backdrop of the illegal nature of the atomic bombings as well as public opinion regarding the issues involved.

The Fukuoka District Court ruled that the law would be applicable to illegal entrants into Japan “so long as they were A-bomb survivors,” with the case also being victorious in appellate court. Japan’s Supreme Court granted issuance of the certificate to Mr. Son, based on its opinion that the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law incorporated characteristics of not only social security but also national compensation. The court also noted that application of the law to Mr. Son’s case included an aspect of “national moral duty” for Japan, in consideration of the historical background. Mr. Kubota said the Supreme Court’s “ruling was good” from that perspective as well.

After receiving the certificate, Mr. Son lived in Japan based on the special permission granted him to stay in the country. On the other hand, there were still many A-bomb survivors living in South Korea and elsewhere overseas who had yet to qualify for aid and relief from Japan.

--------------------

Issuance of A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate, payment of allowances spread slowly

Government directive: “Application limited to survivors in Japan”

In the Son Jin Doo trial, the Fukuoka Prefectural government — the party responsible for handling the administrative work involved in issuance of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, followed guidelines provided by the national government starting from the stage of rejection of the application — asserted that application of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in that case would require the applicant to have a “residential relationship” with Japan. In March 1974, when the ruling in the plaintiff’s favor was handed down by the Fukuoka District Court, the prefectural government appealed the judgment. Meanwhile, in July of that same year, the Tokyo metropolitan government announced its policy of issuing certificates for applications from A-bomb survivors in South Korea while they were in Japan.

One such survivor who submitted an application to the Tokyo government was Shin Yong-su, who experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and died in 1999. At the invitation of a hospital in Tokyo, Mr. Shin visited Japan in June 1974 to undergo treatment for keloids from the bombing he suffered on his face. Two years prior, Mr. Shin had visited Japan as chair of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association and submitted a letter of request to then Deputy Prime Minister Takeo Miki seeking compensation for damages for South Korean A-bomb survivors and application of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law to all non-Japanese A-bomb survivors.

Led by Governor Ryokichi Minobe, whose base of support was the Socialist Party of Japan and the Communist Party, the metropolitan government independently decided to issue the certificate to Mr. Shin, arguing that the issuance was “only natural from the perspective of human rights.” Pushed by the action of Tokyo’s leadership, the national government announced its own policy of a “residential relationship” with Japan being a condition for non-Japanese A-bomb survivors living overseas, so long as their stay in Japan exceeded one month for the stated aim of undergoing medical treatment.

Obtaining the certificate on July 25, Mr. Shin called for “fundamental measures to be adopted,” citing how his case was a legal exception. Japan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare had issued its “Directive No. 402” on July 22, three days before Mr. Shin received the certificate. The directive outlined how even if A-bomb survivors living abroad were able to obtain the certificate in Japan, their legal status as A-bomb survivors in possession of the certificate would be lost upon their return home, disqualifying them from the right to receive allowances provided under the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law.

When the Supreme Court rendered its ruling in favor of the plaintiff in the Son Jin Doo case, the national government announced its policy of issuing the certificate to overseas survivors so long as “they were currently residing in Japan,” applying the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law without regard to the reason. In November 1980, in accordance with an agreement between the governments of Japan and South Korea, an initiative called “Travel to Japan for medical treatment” was established, allowing A-bomb survivors living in South Korea to be admitted to hospitals and undergo treatment in Japan. By 1986, 349 survivors had taken part in the initiative.

However, the framework limited application of the law to only those residing in Japan. Those eligible for treatment under the law were admitted to A-bomb hospitals in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and received the certificate with the hospital’s address identified as their “current address.” Based on the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law, such individuals were able to undergo treatment at hospitals without requiring out-of-pocket payments. Travel expenses were covered by the South Korea government. During their stay in Japan, such survivors were able to receive health management allowances if their applications had been approved, but provision of the allowances was then halted after their return to South Korea, in keeping with Directive No. 402.

In January 1979, the year after the Supreme Court’s ruling, a group known as the Social Security System Council submitted an advisory opinion to the Japanese government with a recommendation for reviewing the basic tenets of aid and relief for A-bomb survivors based on the intent of the court ruling. With that, the Ministry of Health and Welfare established the Conference for Fundamental Issues relating to Measures for A-bomb Survivors, a panel consisting of seven specialists. However, the conference’s recommendations submitted in December 1980 mostly confirmed the measures that were being carried out by the ministry at the time and failed to even touch on the issue of overseas A-bomb survivors.

“Directive No. 402” issued on July 22, 1974, by Ministry of Health and Welfare bureau chief

The law (A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law, which designates payment of allowances and so on) is applied to A-bomb survivors who have a residential relationship with Japan and as such is interpreted to mean that survivors who move beyond Japan’s borders and change their address are ineligible for application of the law.

--------------------

Japanese citizens support application and medical care for overseas survivors, with lawsuit also filed over directive

Korean sufferers of the atomic bombings established the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association in 1967. In the 1970s, aid and relief activities carried out by Japanese citizens, who had taken the association’s calls to heart, began to spread.

Keizaburo Toyonaga, 89, an A-bomb survivor and former high school teacher living in Hiroshima’s Aki Ward, helped found the Hiroshima Branch of the Association of Citizens for Support of South Korean A-bomb Sufferers, an organization originally established in Osaka in 1972. Mr. Toyonaga had visited South Korea in 1971 for training using vacation days from his work and met with local A-bomb survivors belonging to the association. “They were not receiving any relief from either the South Korean government or the Japanese government,” explained Mr. Toyonaga.

In 1974, as part of the association’s activities, Tchye Young Sung, who currently lives in Busan City, South Korea, was invited to Hiroshima for treatment. Torataro Kawamura, an employee at Kawamura Hospital in Hiroshima City who died in 1987, cooperated in the process of accepting Ms. Tchye, who also underwent treatment at the Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital.

Mr. Toyonaga worked to support Ms. Tchye’s receipt of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. She experienced the atomic bombing when she had been mobilized for work in Hiroshima City as a student at Masuda Girls’ High School in Masuda City, Shimane Prefecture. After a later search for her classmates at that time, Mr. Toyonaga found someone able to serve as a witness for her application process. In December 1974, the certificate was issued to her by the Hiroshima City government.

In 1984, Mr. Kawamura and others took the lead and formed the Hiroshima Committee to Invite Korean A-bomb Survivors to Japan for Medical Treatment. The group called into question the fact that the South Korean government was paying the travel expenses for the Korean A-bomb survivors to visit Japan and undergo medical treatment. The committee called widely for donations, which led to all costs for the trip to Japan including the travel expenses being covered. By the end of 2016, a total of 572 A-bomb survivors had been accepted from South Korea.

Starting in the 1970s, the issuance of the certificates and the payment of allowances in Japan were permitted, with supporters of South Korean A-bomb survivors soon questioning the idea of discontinued payment of allowances after the visitors’ return home. According to Kazuyuki Tamura, 82, professor emeritus at Hiroshima University and a resident of the city’s Higashi Ward, people in the 1990s began to have a strong sense of the problems inherent in Directive No. 402, which the national government was using as the basis for its laws, and offered their support for court battles waged by A-bomb survivors in South Korea, Brazil, and the United States.

In 1998, South Korean A-bomb survivor Kwak Kwi Hoon, who died in 2022, filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government and the Osaka Prefectural government at the Osaka District Court, claiming that discontinuation of his health management allowance payment based on Directive No. 402 was illegal. Mr. Kwak won both the first and second cases in 2002, with the national government dropping its appeal.

Afterward, A-bomb survivor plaintiffs living abroad succeeded in their relevant lawsuits, including in a Supreme Court decision over provision of medical expenses in 2015. As the grounds for such rulings, the reasoning of “consideration from a national compensation perspective” used for the ruling in the Son Jin Doo trial was frequently referenced, indicating that the roadblocks standing in the way of offering aid relief to overseas A-bomb survivors had nearly disappeared more than 40 years after Mr. Son’s court case. However, issues still remain, including the fact that A-bomb survivors in North Korea, a country with which Japan does not maintain diplomatic ties, have been left out of measures related to aid and relief.

Timeline of “Son Jin Doo trial” and related events

December 1970

Mr. Son tries to enter Japan illegally and is arrested in Saga Prefecture. He claims he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and demands treatment. A group of citizens aiming to assist Mr. Son is established in Hiroshima.

January 1971

The Karatsu Branch of the Saga District Court sentences Mr. Son to 10 months in prison for his violation of the Immigration Control Order.

June

The Fukuoka High Court rejects Mr. Son’s appeal. He is sent to Fukuoka Prison.

August

The enactment of Mr. Son’s sentence is stayed on the grounds that he requires treatment for tuberculosis and is suspected of suffering from A-bomb disease. He is hospitalized in Fukuoka.

October

Mr. Son submits an application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate to the Fukuoka Prefectural government.

July 1972

The Fukuoka Prefectural government rejects the application for issuance of the certificate.

October

Mr. Son files a lawsuit with the Fukuoka District Court, demanding reversal of the rejection.

January 1973

He is transferred to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima City with support from citizens. A physician involved in medical care for A-bomb survivors examines Mr. Son.

May

After the demand for a suspended sentence is revoked, Mr. Son is sent to Hiroshima Prison. In August, his sentence concludes, and he is sent to the Omura Detention Center in Nagasaki Prefecture.

March 1974

The Fukuoka District Court rules in favor of the plaintiff. The following month, the Fukuoka Prefectural government appeals the ruling.

July

The Tokyo metropolitan government issues the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate to Shin Yong-su, an A-bomb survivor living in South Korea who is temporarily in Japan for treatment. Japan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare issues a notification (known as Directive No. 4o2) regarding treatment of overseas A-bomb survivors who, even if they were to come to Japan and obtain the certificate, would lose the right to receive benefits and other allowances after their return home.

July 1975

Fukuoka High Court rejects the appeal filed by Fukuoka Prefecture in the court case involving Mr. Son’s certificate issue.

January 1976

Mr. Son is provisionally released from the Omura Detention Center due to worsening of his case of tuberculosis. He is hospitalized in Fukuoka.

March 1978

Japan’s Supreme Court rejects the Fukuoka Prefectural government’s final appeal. The next month, Ms. Son is issued the certificate.

June 1976

The Ministry of Health and Welfare establishes the Conference for Fundamental Issues relating to Measures for A-bomb Survivors.

November 1980

Based on an agreement between the Japanese and South Korean governments, an initiative begins under which A-bomb survivors living in South Korea “Travel to Japan for medical treatment.”

(Originally published on April 30, 2025)