Documenting Hiroshima of 1946: August 5 and 6, one year after A-bombing, deepened feelings of longing for the dead

Aug. 6, 2025

by Maho Yamamoto and Minami Yamashita, Staff Writers

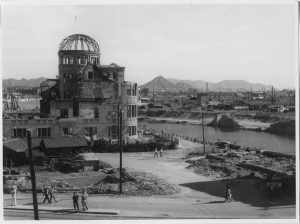

In August 1946, one year after the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, citizens were observed in the city mourning A-bomb victims and pledging recovery of the city, which retained deep scars from the bombing. During the period August 5–7, the Peace Restoration Festival took place near the hypocenter and memorial services were held by schools that had lost many students and by groups of religious adherents. Although Japan at the time was occupied mainly by the U.S. military, which continued to justify the atomic bombings, and citizens struggled to survive day to day, a “wish for peace” arose, traced herein by the Chugoku Shimbun through photographs, written records, and testimonies from that period.

Deep prayers at Peace Restoration Festival, memorial services

Hiroshima citizens gather near hypocenter area, which retained deep scars from bombing

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1946, a siren echoed throughout Hiroshima City, which became enveloped in deep prayers at that time, one year after the atomic bombing. On August 7, the following day, the Chugoku Shimbun reported that, “Streetcars, automobiles and other vehicles as well as passers-by stood still, with workers in offices putting their pens aside. Each solemnly observed one-minute of silent prayer in remembrance of the day of the bombing and to strengthen their commitment to recovery.”

On this day, Shimoko Mihara, 95, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who was a fifth-year student at the time of the bombing at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (present-day Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School), participated in a choral event held in what is now Peace Memorial Park. Tracing her memories of that time, Ms. Mihara said, “The only thing I remember about the event is that I sang my heart out.” She added, “Many people came and went around us. Some of them may have been searching for missing family members.”

One year prior to that day, Ms. Mihara had been blown over by the blast from the atomic bombing while at a temple on Hijiyama Hill (located in the Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), where she had been mobilized as a student for work. She had been trapped under the building but was later rescued by a soldier. A friend of hers from a lower grade in school with whom she had commuted to school together by train every day had gone missing after Ms. Mihara last saw her with serious burns.

Her school had lost a total of more than 350 students, teachers, and staff in the atomic bombing. Classes resumed in October 1945, but according to Ms. Mihara’s recollections, “Students didn’t talk about the atomic bombing.” She starting hearing stories of her friends’ experiences in the bombing only after graduation. “I cremated my father’s body in the garden at home,” said one friend. Another explained how, “My younger brother died in the bombing.” Ms. Mihara said, “I just struggled to deal with the things right in front of me at that time. Now, August 6 is a day for me to put my emotions into memorializing those who died.”

On August 6, 1946, different religious denominations held a memorial service for victims at Hiroshima’s Memorial Monument for the War Victims and a house of worship, both built in the area around the remains of Jisenji Temple in what is now Peace Memorial Park. All of the children at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, in the area of Itsukaichi-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Saeki Ward), attended the service, placing their hands together in prayer.

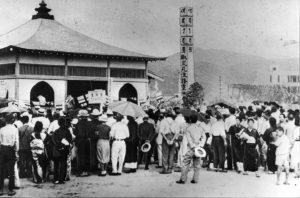

Ahead of the other ceremonies, the Peace Restoration Festival was held on August 5. The citizens’ rally for peace restoration, the festival’s main event, was held in front of the former Gokoku Shrine in the area of Motomachi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), drawing around 7,000 people. Representatives from each of the neighborhood associations in the city attended the rally, carrying placards and banners with such slogans as “World peace, from Hiroshima” and “Recovery of our own community begins with us.” Then-Hiroshima City Mayor Shichiro Kihara called on those in attendance with the words, “United with citizens, let’s strive to construct Peace City Hiroshima as a symbol of world peace.”

The Peace Restoration Festival was organized by a federation of city and town associations that had been formed in May. According to Hiroshima Shinshi Henshu Techo (in English, ‘Editorial notes on Hiroshima’s recent history’), written by the federation’s staff and published in 1979, when the federation had made a request of the Hiroshima City government to hold a restoration festival, the city had rejected the proposal, saying, “Because the occupation armed forces prohibit gatherings, it is virtually impossible for the city government to act as an organizer for such a festival.” After negotiations with the occupying forces, the festival was ultimately permitted to take place on the condition that no specific nation would be disparaged.

As an event related to the festival, Hiroshima City and the Japan Medical Corps set up free health clinics at hospitals in Hiroshima for citizens suffering from so-called “A-bomb disease.” Other efforts involved inviting residents from cities and towns in the vicinity of Hiroshima to movie theaters to show appreciation for their work at the time of the atomic bombing in providing aid and relief to the wounded and preparing emergency meals.

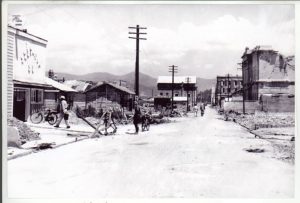

On the Hondori shopping street (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), located close to Peace Memorial Park, shop owners who had survived the bombing were in the process of reopening their shops. According to the publication Hiroshima Hondori Shoten-gai no Ayumi (‘History of the Hondori shopping arcade’), published in 2000, the construction of 10 residential shacks in the area was decided in August, following the opening in early 1946 of two commercial stores — Chuo Shokudo Sohon-ten and the Nakayama Musical Instrument Shop.

In 1947, the “Peace Festival” began under sponsorship of the Hiroshima Peace Festival Association, which was managed by the Hiroshima City government and other organizations. That festival formed the foundation for the modern-day Peace Memorial Ceremony and included the “Peace Declaration” and “Peace Bell,” among other elements.

Christian convention held on ruins of Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church

Declaration contained pledge to recover, reflection on war

On August 6, 1946, Christian adherents in Hiroshima held a convention amid the ruins of Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church (located in the city’s present-day Naka Ward) and announced their Peace Declaration, which included a pledge for peace and reflection on the war. “We sincerely repent for our weakness and lack of action in the past for preventing the horrors of the war,” read the declaration..

On behalf of the attendees, Kazuma Nakao, an A-bomb survivor serving as chair of the Hiroshima YMCA who died in 1976 at the age of 70, read aloud the declaration at the convention. Referring to the scarcity across the board of housing, food, and clothing, he said, “Believing that the practice of brotherhood, which is to love others as oneself, is the only path to overcome the struggles facing us, we hereby offer our earnest prayers for God’s help in faithfully carrying out that practice.”

According to material archived at Nagarekawa Church, Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, one of the authors of the Peace Declaration, shared his thoughts on its purpose. “The declaration must be used as something for us to repent our sins inward, rather than to appeal for peace to others.”

The Hiroshima YMCA, established in 1938, was a place where young church members in the city had fostered friendships with each other before intensification of the war. After the war ended, Mr. Nakao, who was at his workplace in Toyo Kogyo (present-day Mazda Motor Corporation) at the time of the atomic bombing, promoted reconstruction of the church together with others. In November 1946, this group was able to secure a base of operations in the church’s current location of Hatchobori (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). In April 1949, they published Ten Yori no Oinaru Koe (‘Great voices from heaven’), a collection of 16 survivors’ accounts of their experiences in the atomic bombing.

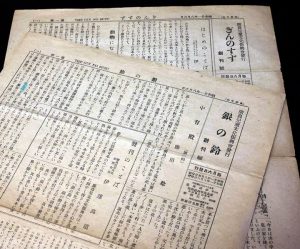

Inaugural issue of children’s magazine “Silver Bell” published

School teachers volunteer to work on magazine’s publication, based on desire to provide guidance for study and spiritual hope

To enhance cultural learning for children, the inaugural issue of Gin no Suzu (‘Silver bell’) was published on August 6, 1946. The magazine was printed by an association for the promotion of children’s culture in Hiroshima, a group made up of volunteer teachers in Hiroshima City, comprising a two-page tabloid printed on both sides of inexpensive straw paper. Two versions of the magazine were created at first, one for students in the lower grades of school and one for students in the higher grades, introducing essays and methods of study.

Takamichi Date, chair of the association and principal at Senda National School (present-day Senda Elementary School) at the time, wrote in the preface of the magazine for readers in the upper grades, “‘Silver Bell’ is a reading material that enriches everyone’s heart, serves as a study guide, and provides a platform for good presentations.”

The Silver Bell for upper-grade students carried student essays about their experiences in returning back to Japan from overseas after the war, as well as methods to be used for study during summer vacation written by teachers. The magazine’s feature article was a children’s story featuring a child who had lost family at the time of the atomic bombing. However, a phrase appearing in the story, “That cursed atomic bomb!!” failed to make it past censorship by the U.S. military-led occupation, with the language ultimately being blacked out in the published magazine.

The second issue of Silver Bell was published in October 1946. That issue was printed in color, based on support from the Hiroshima Printing company provided to the association, which was facing financial difficulties. The number of different publications of the magazine was increased to three, with a version for students in the middle grades being added. That new version contained reading materials suited to what the students were specifically studying, manga comics, and children’s essays. The printing company, ultimately entrusted with editing the magazine, put out requests to renowned writers for submissions to the publication. The magazine attracted readers throughout Japan, with circulation reaching around 1.2 million copies in 1949.

Hogusa Harada, 85, a resident of Akitakata City, still keeps in storage a special edition of the magazine’s November 1949 issue. She was a fourth-year student at Honkawa Elementary School (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) at the time. A photograph of her participation in the planning of a roundtable meeting was used on the cover of the magazine’s special edition. Smiling, Ms. Harada said, “My family couldn’t afford to buy the magazine, so that was the first time I ever had the chance to read it. My mother was so pleased that she bought several copies.”

Ms. Harada had lost her father, Kazuo Nakahara, in the atomic bombing. Her mother, Natsue, raised her four children by running a vegetable and fruit shop. On the day of the magazine’s photo shoot, Natsue had her daughter dressed to the full. She had Hogusa wear a checked dress made from a kimono and tied her hair up with a pink ribbon. Hogusa said, “I was invited to the roundtable meeting because my mother, to honor my father’s wish while he was still alive, had me learn classical Japanese dance.” In memory of her parents, she shows the Silver Bell issue to children at local elementary schools when she speaks with them about her experiences in the atomic bombing.

Song of mourning in memory of classmates and teachers

gSong sung in chorus at Prefectural Girls’ School, which published newspaper that carried students’ experiences in bombin

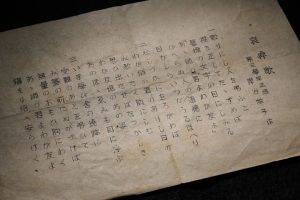

On August 6, 1946, a first-year memorial service for A-bomb victims took place on the ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (Prefectural Girls’ School; present-day Minami High School) in the area of Shimonaka-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward). The Prefectural Girls’ School had lost many students, teachers, and staff in the atomic bombing. Attendees at the service mourned their dead classmates and teachers and joined together in a chorus to sign a song of mourning. The song’s lyrics were written by Shoko Kishitani, a third-year student at the school at the time who died in 2020.

“When I mourn the dead, I straighten up and stand still. The inscriptions on the graves pierce my eyes. Oh, my teachers, my friends — my memories of those who will never return make my eyes fill with tears.” The lyrics, featuring memories of past days of the deceased and the sorrow in losing them, is composed of three verses and culminates with the phrase, “Oh, my teachers, my friends, I pray for the repose of your souls and that you may rest in peace.” Shinichiro Okamoto, the school’s music teacher, composed the song’s music.

Students from the Prefectural Girls’ School had been mobilized on the day of the atomic bombing to help with building-demolition work in the Dobashi area (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), located around 800 meters from the hypocenter. All of the school’s first-year students who were present at the site of the building-demolition work had died in the bombing. A total of 281 students, including those from other school years as well as 20 teachers and staff perished in the bombing.

Prior to the first anniversary of the atomic bombing, the school called for people to submit lyrics for the song of mourning. Ms. Kishitani, whose lyrics were ultimately selected for use in the song, later looked back on those memories in her personal account she had submitted to the publication Yukyu no Makoto: Minami Yuho 90-nen Shi (‘Eternal truth: 90-year history of Minami Yuho High School’), published in 1991. “All my friends who were one year younger than I was and died in the atomic bombing were truly beautiful girls with completely innocent faces.”

Kazuko Kawada, 93, a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward who was in the same year as Ms. Kishitani at school, said with a trembling voice, “Ms. Kishitani loved literature. Her song of mourning, filled with feelings for the dead, truly resonated with me.” Ms. Kawada experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in the area of Takasu (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward), located around 2.5 kilometers from hypocenter, where she had been mobilized for work.

Two days later, she went to an aid and relief station to look for first-year students from her school who she was told had been taken there. Although she asked if students from the school were there, she was unable to find anyone. She added, “One of my young friends from elementary school had entered the Prefectural Girls’ School because she wanted to go to the same school I was attending. She had been so happy to enter the school, but then…” On a memorial monument erected in front of the school’s former front gate are inscribed the three verses of the song of mourning’s lyrics, along with part of its musical score. Each time Ms. Kawada sings the song at the annual memorial ceremony held on August 6, she bursts into tears.

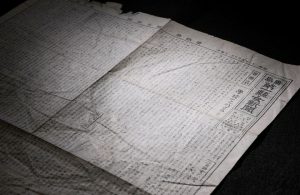

At the Prefectural Girls’ School, the inaugural issue of the “Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ School newspaper” was published on August 6, 1946, by the school’s magazine club members. After the atomic bombing, the school’s students were taking classes at different locations, with the newspaper finally being published soon after all the students had been reunited to resume studying at the former Army Clothing Depot buildings, which still stand in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward. The newspaper included the hope for promoting solidarity among students for restoration of the school.

The newspaper was a double-sided, two-page tabloid. Under the headline “Special Feature: Restoration of Our School,” the newspaper read, “Since we do not have enough school supplies and our families are in dire financial straits, it is quite difficult for us to spend a full day concentrating on our studies. Despite that, we are overcoming the many difficulties and following a path of consistent improvement.”

The newspaper also carried students’ testimonies of their experiences in the atomic bombing titled “That Day,” as well as the lyrics of the song of mourning. Investigating the students’ food and circumstances of their commute to school, the newspaper reported that more than half were suffering from hunger. In some issues, the writers made an attempt to interview experts. Publication of the paper continued through the 14th edition with the same printed title, before the school’s name was changed to Yuho High School in 1948.

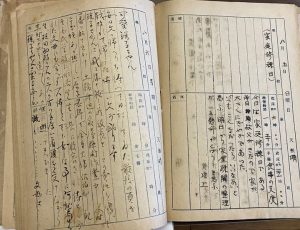

Father described feelings of missing his daughter in her unfinished diary

His song featuring his love for his daughter added to diary

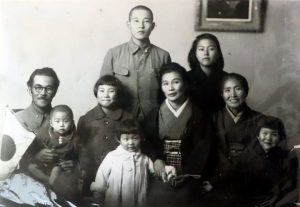

Yoko Moriwaki, 13 at the time, was killed in the atomic bombing when she was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (Prefectural Girls’ School; present-day Minami High School). Her diary stopped at the time of the entry dated August 5, 1945. But the diary’s following page, which was dated August 6, included the writing of her father, Ataru Moriwaki, who died in 1993 at the age of 84, with information about his daughter’s death and his own feelings about the loss after he had returned from military service in China in 1946. “As the father returning from defeat in war and missing her, I have filled in the last page of her diary, which she had kept every day awaiting my return.”

On August 6, 1945, Yoko had been mobilized to help with building-demolition work, leaving her home on Miyajima Island (in Hiroshima’s present-day Hatsukaichi City) for the Dobashi area (now in the city’s Naka Ward). She suffered burns over her entire bombing and was taken to Kannon National School in the village of Kannon (in Hiroshima’s present-day Saeki Ward) but died later that night.

Her father, Ataru, who had been a music teacher who wished for “Yoko’s soul to rest in peace,” wrote on the next page of the diary “Musume Itoshi (‘Love for my daughter’),” a song he had written and composed in February 1946, prior to his return to Japan at a time when he knew nothing of his daughter’s death. Originally, his song expressed a scene of his family awaiting his return in their hometown in a bright, major key, but he later rewrote the song in a minor key.

Yoko loved her father very much. In an essay she had completed when she was in the third year at the national school, she wrote, “My beloved dad looks very happy every time I smile.” She added, “He sometimes goes to Hiroshima and buys me lots of souvenirs. I love my dad.” She had dreamed of becoming a music teacher like him.

With thoughts of his daughter, Ataru went back to teaching at the school and started directing a brass band at Miyajima Junior High School. Later, he also opened a private music school for piano and marimba at his home. While he had moved forward with his life, he also wrote in a personal account at the age of 77 about how, “It is almost impossible to describe in words my sense of despair and the emptiness of war.”

The story of Yoko’s diary continued. Her mother, Masae Moriwaki, who died in 1980 at the age of 76, added the entry “A decade after the death of Yoko.” Masae wrote, “No matter how sad, lonely, or painful the times were, I did my best and managed to survive so long as my husband was alive.” Holding her daughter’s diary, she would cry and cry.

Yoko’s diary was passed down in the family through Koji Hosokawa, Yoko’s older brother who died in 2023 at the age of 95. In June this year, the diary was donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by Yo Hosokawa, 66, Mr. Hosokawa’s oldest son who lives in the city’s Naka Ward. Mr. Hosokawa said, “Despite barely making it back to Japan alive, my grandfather did not know of Yoko’s death until his return. He probably wrote down his feelings of repentance and desire to pray for the repose of her soul.” When he shares his family’s experience in the atomic bombing as a hibakusha family member legacy successor, Yo sings his grandfather’s song “Love for my daughter,” explaining that his grandfather had written the song in her diary on August 6, 1946.

Mother finds work pants of missing daughter amid scorched ruins

Holding the daughter’s pants, she would cry herself to sleep

On August 6, 1946, part of a pair of monpe pants, traditional Japanese pants worn for work, Miyoko Matsumoto was wearing at the time of the atomic bombing, was found by her mother, Masa Matsumoto, in the scorched ruins of the city. Miyoko, 14 at the time of the bombing and a second-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (present-day Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School), had gone missing after she experienced the atomic bombing in the area of Zakoba-cho in Hiroshima City, around 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, where she had been mobilized to help with building-demolition work.

Masa had been in the fields behind their home in the area of Ushita-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Higashi Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. She continued to search for her daughter, who had failed to return home, and went to Zakoba-cho on this day. When she dug out a tattered piece of monpe from the ground, she found it had the same pattern as that of the pants her daughter had been wearing one year before.

“She wrapped the muddy monpe in a newspaper, held the pants, and cried herself to sleep,” wrote Sachiko Miyata, Miyoko’s older sister by six years about her mother in a personal account she submitted to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Her mother asked Sachiko to burn Miyoko’s monpe with her body when she finally died and was cremated. However, Ms. Miyata convinced her to hold on to the pants, saying, “They must be kept in order to prevent such a horrible thing from ever happening again.” In that way, in 1997, Miyoko’s monpe were donated to the museum.

(Originally published on August 6, 2025)

In August 1946, one year after the U.S. military dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, citizens were observed in the city mourning A-bomb victims and pledging recovery of the city, which retained deep scars from the bombing. During the period August 5–7, the Peace Restoration Festival took place near the hypocenter and memorial services were held by schools that had lost many students and by groups of religious adherents. Although Japan at the time was occupied mainly by the U.S. military, which continued to justify the atomic bombings, and citizens struggled to survive day to day, a “wish for peace” arose, traced herein by the Chugoku Shimbun through photographs, written records, and testimonies from that period.

“Silent prayer was solemnly observed in remembrance of the day of the bombing and to strengthen commitment to recovery”

Deep prayers at Peace Restoration Festival, memorial services

Hiroshima citizens gather near hypocenter area, which retained deep scars from bombing

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1946, a siren echoed throughout Hiroshima City, which became enveloped in deep prayers at that time, one year after the atomic bombing. On August 7, the following day, the Chugoku Shimbun reported that, “Streetcars, automobiles and other vehicles as well as passers-by stood still, with workers in offices putting their pens aside. Each solemnly observed one-minute of silent prayer in remembrance of the day of the bombing and to strengthen their commitment to recovery.”

On this day, Shimoko Mihara, 95, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward who was a fifth-year student at the time of the bombing at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (present-day Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School), participated in a choral event held in what is now Peace Memorial Park. Tracing her memories of that time, Ms. Mihara said, “The only thing I remember about the event is that I sang my heart out.” She added, “Many people came and went around us. Some of them may have been searching for missing family members.”

One year prior to that day, Ms. Mihara had been blown over by the blast from the atomic bombing while at a temple on Hijiyama Hill (located in the Hiroshima’s present-day Minami Ward), where she had been mobilized as a student for work. She had been trapped under the building but was later rescued by a soldier. A friend of hers from a lower grade in school with whom she had commuted to school together by train every day had gone missing after Ms. Mihara last saw her with serious burns.

Her school had lost a total of more than 350 students, teachers, and staff in the atomic bombing. Classes resumed in October 1945, but according to Ms. Mihara’s recollections, “Students didn’t talk about the atomic bombing.” She starting hearing stories of her friends’ experiences in the bombing only after graduation. “I cremated my father’s body in the garden at home,” said one friend. Another explained how, “My younger brother died in the bombing.” Ms. Mihara said, “I just struggled to deal with the things right in front of me at that time. Now, August 6 is a day for me to put my emotions into memorializing those who died.”

On August 6, 1946, different religious denominations held a memorial service for victims at Hiroshima’s Memorial Monument for the War Victims and a house of worship, both built in the area around the remains of Jisenji Temple in what is now Peace Memorial Park. All of the children at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, in the area of Itsukaichi-cho (in Hiroshima’s present-day Saeki Ward), attended the service, placing their hands together in prayer.

Ahead of the other ceremonies, the Peace Restoration Festival was held on August 5. The citizens’ rally for peace restoration, the festival’s main event, was held in front of the former Gokoku Shrine in the area of Motomachi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), drawing around 7,000 people. Representatives from each of the neighborhood associations in the city attended the rally, carrying placards and banners with such slogans as “World peace, from Hiroshima” and “Recovery of our own community begins with us.” Then-Hiroshima City Mayor Shichiro Kihara called on those in attendance with the words, “United with citizens, let’s strive to construct Peace City Hiroshima as a symbol of world peace.”

The Peace Restoration Festival was organized by a federation of city and town associations that had been formed in May. According to Hiroshima Shinshi Henshu Techo (in English, ‘Editorial notes on Hiroshima’s recent history’), written by the federation’s staff and published in 1979, when the federation had made a request of the Hiroshima City government to hold a restoration festival, the city had rejected the proposal, saying, “Because the occupation armed forces prohibit gatherings, it is virtually impossible for the city government to act as an organizer for such a festival.” After negotiations with the occupying forces, the festival was ultimately permitted to take place on the condition that no specific nation would be disparaged.

As an event related to the festival, Hiroshima City and the Japan Medical Corps set up free health clinics at hospitals in Hiroshima for citizens suffering from so-called “A-bomb disease.” Other efforts involved inviting residents from cities and towns in the vicinity of Hiroshima to movie theaters to show appreciation for their work at the time of the atomic bombing in providing aid and relief to the wounded and preparing emergency meals.

On the Hondori shopping street (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), located close to Peace Memorial Park, shop owners who had survived the bombing were in the process of reopening their shops. According to the publication Hiroshima Hondori Shoten-gai no Ayumi (‘History of the Hondori shopping arcade’), published in 2000, the construction of 10 residential shacks in the area was decided in August, following the opening in early 1946 of two commercial stores — Chuo Shokudo Sohon-ten and the Nakayama Musical Instrument Shop.

In 1947, the “Peace Festival” began under sponsorship of the Hiroshima Peace Festival Association, which was managed by the Hiroshima City government and other organizations. That festival formed the foundation for the modern-day Peace Memorial Ceremony and included the “Peace Declaration” and “Peace Bell,” among other elements.

Christian adherents deliver peace declaration

Christian convention held on ruins of Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church

Declaration contained pledge to recover, reflection on war

On August 6, 1946, Christian adherents in Hiroshima held a convention amid the ruins of Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church (located in the city’s present-day Naka Ward) and announced their Peace Declaration, which included a pledge for peace and reflection on the war. “We sincerely repent for our weakness and lack of action in the past for preventing the horrors of the war,” read the declaration..

On behalf of the attendees, Kazuma Nakao, an A-bomb survivor serving as chair of the Hiroshima YMCA who died in 1976 at the age of 70, read aloud the declaration at the convention. Referring to the scarcity across the board of housing, food, and clothing, he said, “Believing that the practice of brotherhood, which is to love others as oneself, is the only path to overcome the struggles facing us, we hereby offer our earnest prayers for God’s help in faithfully carrying out that practice.”

According to material archived at Nagarekawa Church, Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, one of the authors of the Peace Declaration, shared his thoughts on its purpose. “The declaration must be used as something for us to repent our sins inward, rather than to appeal for peace to others.”

The Hiroshima YMCA, established in 1938, was a place where young church members in the city had fostered friendships with each other before intensification of the war. After the war ended, Mr. Nakao, who was at his workplace in Toyo Kogyo (present-day Mazda Motor Corporation) at the time of the atomic bombing, promoted reconstruction of the church together with others. In November 1946, this group was able to secure a base of operations in the church’s current location of Hatchobori (in the city’s present-day Naka Ward). In April 1949, they published Ten Yori no Oinaru Koe (‘Great voices from heaven’), a collection of 16 survivors’ accounts of their experiences in the atomic bombing.

Inaugural issue of children’s magazine “Silver Bell” published

School teachers volunteer to work on magazine’s publication, based on desire to provide guidance for study and spiritual hope

To enhance cultural learning for children, the inaugural issue of Gin no Suzu (‘Silver bell’) was published on August 6, 1946. The magazine was printed by an association for the promotion of children’s culture in Hiroshima, a group made up of volunteer teachers in Hiroshima City, comprising a two-page tabloid printed on both sides of inexpensive straw paper. Two versions of the magazine were created at first, one for students in the lower grades of school and one for students in the higher grades, introducing essays and methods of study.

Takamichi Date, chair of the association and principal at Senda National School (present-day Senda Elementary School) at the time, wrote in the preface of the magazine for readers in the upper grades, “‘Silver Bell’ is a reading material that enriches everyone’s heart, serves as a study guide, and provides a platform for good presentations.”

The Silver Bell for upper-grade students carried student essays about their experiences in returning back to Japan from overseas after the war, as well as methods to be used for study during summer vacation written by teachers. The magazine’s feature article was a children’s story featuring a child who had lost family at the time of the atomic bombing. However, a phrase appearing in the story, “That cursed atomic bomb!!” failed to make it past censorship by the U.S. military-led occupation, with the language ultimately being blacked out in the published magazine.

The second issue of Silver Bell was published in October 1946. That issue was printed in color, based on support from the Hiroshima Printing company provided to the association, which was facing financial difficulties. The number of different publications of the magazine was increased to three, with a version for students in the middle grades being added. That new version contained reading materials suited to what the students were specifically studying, manga comics, and children’s essays. The printing company, ultimately entrusted with editing the magazine, put out requests to renowned writers for submissions to the publication. The magazine attracted readers throughout Japan, with circulation reaching around 1.2 million copies in 1949.

Hogusa Harada, 85, a resident of Akitakata City, still keeps in storage a special edition of the magazine’s November 1949 issue. She was a fourth-year student at Honkawa Elementary School (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward) at the time. A photograph of her participation in the planning of a roundtable meeting was used on the cover of the magazine’s special edition. Smiling, Ms. Harada said, “My family couldn’t afford to buy the magazine, so that was the first time I ever had the chance to read it. My mother was so pleased that she bought several copies.”

Ms. Harada had lost her father, Kazuo Nakahara, in the atomic bombing. Her mother, Natsue, raised her four children by running a vegetable and fruit shop. On the day of the magazine’s photo shoot, Natsue had her daughter dressed to the full. She had Hogusa wear a checked dress made from a kimono and tied her hair up with a pink ribbon. Hogusa said, “I was invited to the roundtable meeting because my mother, to honor my father’s wish while he was still alive, had me learn classical Japanese dance.” In memory of her parents, she shows the Silver Bell issue to children at local elementary schools when she speaks with them about her experiences in the atomic bombing.

“All my friends who died in the atomic bombing still had innocent faces”

Song of mourning in memory of classmates and teachers

gSong sung in chorus at Prefectural Girls’ School, which published newspaper that carried students’ experiences in bombin

On August 6, 1946, a first-year memorial service for A-bomb victims took place on the ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (Prefectural Girls’ School; present-day Minami High School) in the area of Shimonaka-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward). The Prefectural Girls’ School had lost many students, teachers, and staff in the atomic bombing. Attendees at the service mourned their dead classmates and teachers and joined together in a chorus to sign a song of mourning. The song’s lyrics were written by Shoko Kishitani, a third-year student at the school at the time who died in 2020.

“When I mourn the dead, I straighten up and stand still. The inscriptions on the graves pierce my eyes. Oh, my teachers, my friends — my memories of those who will never return make my eyes fill with tears.” The lyrics, featuring memories of past days of the deceased and the sorrow in losing them, is composed of three verses and culminates with the phrase, “Oh, my teachers, my friends, I pray for the repose of your souls and that you may rest in peace.” Shinichiro Okamoto, the school’s music teacher, composed the song’s music.

Students from the Prefectural Girls’ School had been mobilized on the day of the atomic bombing to help with building-demolition work in the Dobashi area (in Hiroshima’s present-day Naka Ward), located around 800 meters from the hypocenter. All of the school’s first-year students who were present at the site of the building-demolition work had died in the bombing. A total of 281 students, including those from other school years as well as 20 teachers and staff perished in the bombing.

Prior to the first anniversary of the atomic bombing, the school called for people to submit lyrics for the song of mourning. Ms. Kishitani, whose lyrics were ultimately selected for use in the song, later looked back on those memories in her personal account she had submitted to the publication Yukyu no Makoto: Minami Yuho 90-nen Shi (‘Eternal truth: 90-year history of Minami Yuho High School’), published in 1991. “All my friends who were one year younger than I was and died in the atomic bombing were truly beautiful girls with completely innocent faces.”

Kazuko Kawada, 93, a resident of Hiroshima’s Minami Ward who was in the same year as Ms. Kishitani at school, said with a trembling voice, “Ms. Kishitani loved literature. Her song of mourning, filled with feelings for the dead, truly resonated with me.” Ms. Kawada experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in the area of Takasu (in the city’s present-day Nishi Ward), located around 2.5 kilometers from hypocenter, where she had been mobilized for work.

Two days later, she went to an aid and relief station to look for first-year students from her school who she was told had been taken there. Although she asked if students from the school were there, she was unable to find anyone. She added, “One of my young friends from elementary school had entered the Prefectural Girls’ School because she wanted to go to the same school I was attending. She had been so happy to enter the school, but then…” On a memorial monument erected in front of the school’s former front gate are inscribed the three verses of the song of mourning’s lyrics, along with part of its musical score. Each time Ms. Kawada sings the song at the annual memorial ceremony held on August 6, she bursts into tears.

At the Prefectural Girls’ School, the inaugural issue of the “Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ School newspaper” was published on August 6, 1946, by the school’s magazine club members. After the atomic bombing, the school’s students were taking classes at different locations, with the newspaper finally being published soon after all the students had been reunited to resume studying at the former Army Clothing Depot buildings, which still stand in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward. The newspaper included the hope for promoting solidarity among students for restoration of the school.

The newspaper was a double-sided, two-page tabloid. Under the headline “Special Feature: Restoration of Our School,” the newspaper read, “Since we do not have enough school supplies and our families are in dire financial straits, it is quite difficult for us to spend a full day concentrating on our studies. Despite that, we are overcoming the many difficulties and following a path of consistent improvement.”

The newspaper also carried students’ testimonies of their experiences in the atomic bombing titled “That Day,” as well as the lyrics of the song of mourning. Investigating the students’ food and circumstances of their commute to school, the newspaper reported that more than half were suffering from hunger. In some issues, the writers made an attempt to interview experts. Publication of the paper continued through the 14th edition with the same printed title, before the school’s name was changed to Yuho High School in 1948.

“Missing her, I have filled in the last page of her diary, which she had kept every day awaiting my return.”

Father described feelings of missing his daughter in her unfinished diary

His song featuring his love for his daughter added to diary

Yoko Moriwaki, 13 at the time, was killed in the atomic bombing when she was a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (Prefectural Girls’ School; present-day Minami High School). Her diary stopped at the time of the entry dated August 5, 1945. But the diary’s following page, which was dated August 6, included the writing of her father, Ataru Moriwaki, who died in 1993 at the age of 84, with information about his daughter’s death and his own feelings about the loss after he had returned from military service in China in 1946. “As the father returning from defeat in war and missing her, I have filled in the last page of her diary, which she had kept every day awaiting my return.”

On August 6, 1945, Yoko had been mobilized to help with building-demolition work, leaving her home on Miyajima Island (in Hiroshima’s present-day Hatsukaichi City) for the Dobashi area (now in the city’s Naka Ward). She suffered burns over her entire bombing and was taken to Kannon National School in the village of Kannon (in Hiroshima’s present-day Saeki Ward) but died later that night.

Her father, Ataru, who had been a music teacher who wished for “Yoko’s soul to rest in peace,” wrote on the next page of the diary “Musume Itoshi (‘Love for my daughter’),” a song he had written and composed in February 1946, prior to his return to Japan at a time when he knew nothing of his daughter’s death. Originally, his song expressed a scene of his family awaiting his return in their hometown in a bright, major key, but he later rewrote the song in a minor key.

Yoko loved her father very much. In an essay she had completed when she was in the third year at the national school, she wrote, “My beloved dad looks very happy every time I smile.” She added, “He sometimes goes to Hiroshima and buys me lots of souvenirs. I love my dad.” She had dreamed of becoming a music teacher like him.

With thoughts of his daughter, Ataru went back to teaching at the school and started directing a brass band at Miyajima Junior High School. Later, he also opened a private music school for piano and marimba at his home. While he had moved forward with his life, he also wrote in a personal account at the age of 77 about how, “It is almost impossible to describe in words my sense of despair and the emptiness of war.”

The story of Yoko’s diary continued. Her mother, Masae Moriwaki, who died in 1980 at the age of 76, added the entry “A decade after the death of Yoko.” Masae wrote, “No matter how sad, lonely, or painful the times were, I did my best and managed to survive so long as my husband was alive.” Holding her daughter’s diary, she would cry and cry.

Yoko’s diary was passed down in the family through Koji Hosokawa, Yoko’s older brother who died in 2023 at the age of 95. In June this year, the diary was donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by Yo Hosokawa, 66, Mr. Hosokawa’s oldest son who lives in the city’s Naka Ward. Mr. Hosokawa said, “Despite barely making it back to Japan alive, my grandfather did not know of Yoko’s death until his return. He probably wrote down his feelings of repentance and desire to pray for the repose of her soul.” When he shares his family’s experience in the atomic bombing as a hibakusha family member legacy successor, Yo sings his grandfather’s song “Love for my daughter,” explaining that his grandfather had written the song in her diary on August 6, 1946.

Mother finds work pants of missing daughter amid scorched ruins

Holding the daughter’s pants, she would cry herself to sleep

On August 6, 1946, part of a pair of monpe pants, traditional Japanese pants worn for work, Miyoko Matsumoto was wearing at the time of the atomic bombing, was found by her mother, Masa Matsumoto, in the scorched ruins of the city. Miyoko, 14 at the time of the bombing and a second-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ High School (present-day Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School), had gone missing after she experienced the atomic bombing in the area of Zakoba-cho in Hiroshima City, around 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, where she had been mobilized to help with building-demolition work.

Masa had been in the fields behind their home in the area of Ushita-machi (in Hiroshima’s present-day Higashi Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. She continued to search for her daughter, who had failed to return home, and went to Zakoba-cho on this day. When she dug out a tattered piece of monpe from the ground, she found it had the same pattern as that of the pants her daughter had been wearing one year before.

“She wrapped the muddy monpe in a newspaper, held the pants, and cried herself to sleep,” wrote Sachiko Miyata, Miyoko’s older sister by six years about her mother in a personal account she submitted to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Her mother asked Sachiko to burn Miyoko’s monpe with her body when she finally died and was cremated. However, Ms. Miyata convinced her to hold on to the pants, saying, “They must be kept in order to prevent such a horrible thing from ever happening again.” In that way, in 1997, Miyoko’s monpe were donated to the museum.

(Originally published on August 6, 2025)