Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing: From August 6, 1945, to 2025 — Devastation from nuclear weapons must be recorded in human world history

Jun. 29, 2025

“May this record of our photographs forever be the last of its kind”

The Chugoku Shimbun’s “Documenting Hiroshima” series of articles reports on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the lives of the city’s citizens afterward. From August of last year, the newspaper has published a total of 357 articles in four series and a 14-page special feature tracing the 80 years since the atomic bombings. The photographs, personal accounts, journals, and testimonies of experiences in the atomic bombing covered in the articles reflect that history as seen by people forced to endure the horrors of nuclear weapons and war. Designating that situation as “world history” shared by all of humanity lays the foundation for truly confronting the crises marked by the deepening divide surrounding the issue of nuclear weapons and by the endless fires of war. Today, the 29,182nd day since the atomic bombings, efforts to preserve and communicate to the world such “documents,” which are surely heritage for all humankind, continue today.

Based on collaboration with media companies, special exhibition of A-bombing photographs and documentary films held in Tokyo

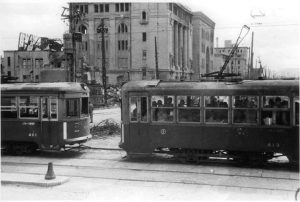

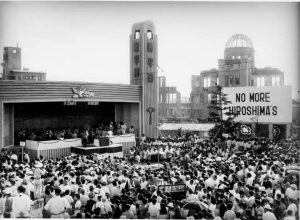

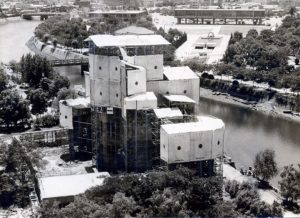

Starting in June 2025, “Hiroshima 1945: Special Exhibition 80 Years after Atomic Bombing,” a collection of A-bombing photographs and documentary films shot in Hiroshima in 1945, has been held at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, located in Tokyo’s Meguro Ward. A total of 164 items recorded by Hiroshima’s citizens, photojournalists, and professional photographers are displayed in the exhibition.

This event is organized jointly by three newspaper companies — the Chugoku Shimbun, Asahi Shimbun, and Mainichi Newspapers — as well as RCC Broadcasting and Kyodo News. This is the first A-bombing photo exhibition held in collaboration with the media utilizing materials that they have preserved and utilized. The impetus for holding the exhibition was an initiative to apply for listing of such materials with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s “Memory of the World” International Register.

Under the shared recognition that the role of the materials as a primary source of information that conveys the tragedy to human beings resulting from war and nuclear weapons’ use has increased as A-bomb survivors continue to grow older, the Chugoku Shimbun served as the secretariat office for the project. In 2023, six parties — the three newspaper organizations that served as the exhibition’s co-organizers, RCC Broadcasting, the Hiroshima City government, and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK) — made a joint application to UNESCO in 2023 of the “Visual archive of Hiroshima atomic bombing – Photographs and films in 1945,” which contained 1,532 photos and two documentary films related to the atomic bombing originally recorded by 27 people and two organizations.

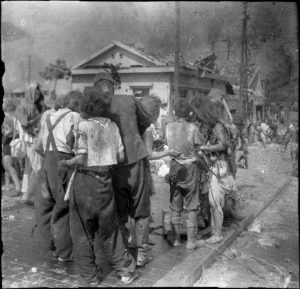

Of those materials, the photos from August 6, 1945, were taken by those who themselves had experienced the atomic bombing and stared death in the face. They included five photos recording the dire situation faced by citizens taken by Yoshito Matsushige, a staff photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun at the time who died in 2005, and photos of the mushroom cloud captured from the ground and of the downtown area in flames taken by local citizens who later joined the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima, an organization formed in 1978.

Meanwhile, staff photographers from the Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Newspapers in Osaka arrived in Hiroshima City on August 9, 1945, taking photos of wounded citizens and the scorched ruins of the city. Among other photos of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima that had been taken by journalists and photographers from Japanese newspapers and media organizations in 1945, only those from the Domei News Agency wire service, passed on to the news agency Kyodo News, are confirmed to exist today.

The materials of Shunkichi Kikuchi, a photographer who had taken many photographs in October 1945 as he accompanied a scientific survey team and who died in 1990, were also included in the materials in the UNESCO application, with cooperation from his bereaved family. RCC Broadcasting and NHK have been involved in the preservation and utilization of the documentary footage filmed by the Nippon Eigasha film production company.

In July 2024, the applicants jointly launched a special website in both Japanese and English to introduce the materials included in the application. Ryo Koyama, an associate professor specializing in modern and contemporary Japanese history at the graduate school of Hokkaido University who specializes in photographic records of war damage, said, “It is a groundbreaking project because access to the photos in the possession of different media organizations and bereaved families of those who took the photos is readily available. The initiatives triggered by the application, including the special exhibition, are meaningful in and of themselves.”

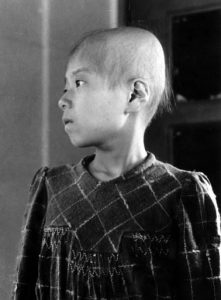

The series “Documenting Hiroshima of 1945” (comprising 153 articles from August 5 through December 31 of last year) dug into the stories behind the photos and film footage, with a focus on the materials submitted for registration application, along with related testimonies of experiences in the atomic bombing and personal accounts. Each of the articles about the photos was published on the same date the photo had been taken, or at least during the same period of time. The series of articles explores the reality of the A-bomb devastation until the end of December 1945, a period during which 140,000 people (with a margin of error of +/- 10,000) are estimated to have died. Pursuing the changes in the daily situation in the city and to its citizens after the bombing, the articles verified additional photos not contained in the application, including those taken by the U.S. military, resulting in the thorough examination of more than 3,000 photos taken in 1945.

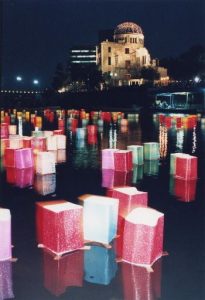

The special exhibition also exhibits the materials in chronological order, incorporating testimonies of experiences in the atomic bombing and personal accounts introduced in the article series into many of the descriptions accompanying the photos. The exhibition explains how the photographers voluntarily held on to their own materials, having resisted an order by the Japanese military to incinerate them and the U.S. military’s demand for submission of the materials. The wish of the photographer Shigeo Hayashi, who took a panoramic photo of Hiroshima’s A-bombed ruins and died in 2002, reads, “May this record of our photographs forever be the last of its kind.”

The Memory of the World application to have the photos and films of the horrific tragedy that must never be repeated serve as the heritage of all of humanity was advanced to reflect the wishes of the photographers, ultimately receiving a recommendation for application by the Japanese government. However, a UNESCO executive board meeting held in April earlier this year, during which was discussed new registration items, did not include the application as an agenda item, meaning the registration of the photographic and film record was put off this time. Neither UNESCO nor the Japanese government has disclosed the reasons for the postponement.

The next registration is scheduled in two years’ time. The co-applicants aim to continue to pursue registration of the materials, saying, “The materials will play an ever more vital role in the future along the path toward the realization of international peace,” according to a comment made by the project’s secretariat office. Meanwhile, the special exhibition at the museum is scheduled to continue through August 17, spanning the date commemorating the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

How to utilize documents about A-bomb survivors’ movement for the future?

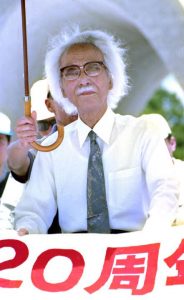

In December 2024, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The group’s work has been etched into history as peace movement symbolic of the world’s “nuclear age.” Meanwhile, preservation and utilization of materials conveying the history of Nihon Hidankyo’s activities have only just begun. The series “Documenting Hiroshima 80 years after A-bombing” (comprising 145 articles since January 1 this year) has widely reported on such documents, such as those newly entrusted to public facilities, in pursuit of the path taken by the movement from a variety of perspectives.

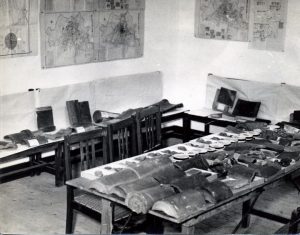

A total of 160 documents left behind by Nihon Hidankyo’s first secretary-general, Heiichi Fujii, who died in 1996, were donated by Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University to whom their care had been entrusted, to the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives in 2019. They serve as a primary source of the movement’s information involving the first World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs held in Hiroshima City in 1955 as well as the formative period of Nihon Hidankyo.

Included in Mr. Fujii’s materials is “Message to the World,” a document drafted by Ichiro Moritaki, the first co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo who died in 1994, for the Conference of A-bomb Sufferers in Hiroshima Prefecture, held in March 1956. The message reads, “If the document could serve as a fortress in protecting the life and happiness of humanity, we would be able to proclaim with all sincerity, ‘We are glad to be alive.’” In August that year, Mr. Moritaki revised the message slightly and read it out as a declaration announcing the establishment of the Nihon Hidankyo organization.

While working as a professor at Hiroshima University, Mr. Moritaki was engaged in Nihon Hidankyo’s activities and left behind an enormous number of documents. From 2018 through the spring of 2025, the Hiroshima University Archives, located in Higashihiroshima City, took in more than 10,000 separate items of his materials, which the facility continues to arrange and organize. Mr. Moritaki’s second daughter, Haruko Moritaki, 86, a resident of Hiroshima’s Saeki Ward, continues to hold on to other of his materials, such as Saiyaku-ki (in English, ‘Chronicle of the disaster’), in which he had recorded his experiences in the atomic bombing immediately after the event.

Besides the materials from those two survivors, other survivors’ documents remain in Hiroshima, including those of Kiyoshi Kikkawa, archived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, who became known as “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1,” served as a pioneer in the A-bomb survivors’ movement, and died in 1986. At the same time, other documents stored both in and outside Hiroshima Prefecture convey the history of how post-war citizens’ movements originating from the atomic bombing spread in diverse ways beyond Nihon Hidankyo.

Some examples are materials related to the “Peace Festival” (archived at the Hiroshima Municipal Archive), a celebration that got its start two years after the atomic bombing; the materials of Ichiro Kawamoto (archived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum), who was a facilitator of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, which called for preservation of the A-bomb Dome; and documents involving the so-called “A-bomb trial” (archived at the Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms).

In 2023, materials from an A-bomb survivors’ group in Brazil were donated to the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association. Such materials, along with documents archived at the Hiroshima University Archives involving a lawsuit filed by Son Jin Doo, a South Korean A-bomb survivor who received support from supporters such as Takashi Hiraoka, 97, a former staff writer at the Chugoku Shimbun who lives in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, comprise a precious record of A-bomb survivors living overseas.

In this series of articles, staff writers investigated documents archived at more than 20 public facilities and organizations located both in and outside Hiroshima Prefecture, reporting on the A-bomb survivors’ movement at multiple levels. However, unlike other kinds of A-bombed materials such as what is known as the “Charred lunchbox,” many of the written materials have not been fully utilized even in the A-bombed city. It is now necessary to engage in debate about how to take advantage of such information for the future as materials in which are recorded appeals made by A-bomb survivors who are no longer alive as well as support from citizens transcending national borders, functioning as “a fortress in protecting the life and happiness of humanity.”

“Testimonies” traced and communicated

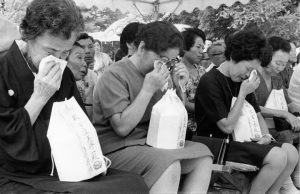

Those who suffered at the hands of the atomic bombings had different experiences at the time of the bombing and in their lives after the war. Not all joined the A-bomb survivors’ movement and raised their voices. But the lives they have lived over the 80 years since “that day,” August 6, 1945, vividly convey what the war and the atomic bombings brought about in humanity.

In the series titled “Documenting Hiroshima, Witnesses to horrors of atomic bombing” (comprising a total of 17 articles featuring six people), staff writers repeatedly paid visits to those suffering from the atomic bombings to listen to the testimonies of their experiences. Junko Okamoto, 95, a resident of Hiroshima City’s Minami Ward, recalled her memories of having walked around the scorched ruins in search of her mother. Tsunehiro Tomoda, 89, a resident of Kadoma City in Osaka Prefecture, had been left an orphan by the atomic bombing. Mr. Tomoda traveled overseas with his Korean acquaintance and, with that, also experienced the Korean War. With the belief that “both war and the atomic bombings are intolerable,” he met with a staff writer and spoke about his life.

The generation that experienced the atomic bombings as schoolchildren are now in their late 80s and 90s and form the core of the opportunity for us to listen to firsthand memories of the tragedy. It is also possible, however, to trace the “testimonies” of the experiences of the event by A-bomb survivors of older generations captured in videos and personal accounts.

In the 1980s, the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, an organization affiliated with the Hiroshima City government, worked on a full-scale project for the filming of A-bomb survivors’ testimonies. The Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims has made publicly available around 1,500 such videos, including those produced by the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. The facility also has in its archives more than 150,000 personal accounts of survivors, providing the public access to many stories about the grievous emotions of parents who had lost children, among others.

The series “1946” (comprising 42 articles by June 27, 2025) captures the lives of citizens and the city itself in the year after the atomic bombing. An important source of information for this series were articles published in the Chugoku Shimbun at that time. Despite the restrictions on the content of the articles, including any criticism against the U.S. military, which had dropped the atomic bombs, as well as any mention of the inhumane nature of the weapons, the newspapers that year recorded the voices of the working generation that lived amidst the scorched ruins and committed themselves to the city’s recovery.

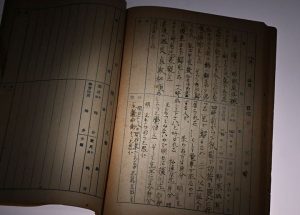

Meanwhile, many victims lost their lives in the atomic bombings without any awareness of what had happened. That series’ first article reported on the diary of one such victim, Fujie Yoneda, who was 13 at the time of the bombing. On June 29, 1945, Ms. Yoneda had written in her diary, “Today, I quietly studied during the self-study period. I hope to continue this practice.” On August 6, 38 days later, her diary entries stopped. The endless empty pages of the diary speak to the reality of war and the use of nuclear weapon in “a voice of silence.”

Citizens’ history: “right to live” put to test

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Senior Staff Writer

The “Hiroshima 1945” special exhibition has on display five photos taken by Yoshito Matsushige in Hiroshima City taken immediately after the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945. The name of a young boy who was captured from the rear in Mr. Matsushige’s second photo taken at the west end of Miyuki Bridge includes a written description based on the personal account of the boy’s father, who had come forward after the war to claim that the boy in the photo was his own son. The boy is introduced as Akira Kutsuki, a first-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Junior High School at the time who had experienced the atomic bombing while engaged in work as a mobilized student.

“That is undoubtedly him,” said two of Mr. Kusuki’s former classmates at a national school in the series “Documenting Hiroshima of 1945,” conveying their experiences in the atomic bombing and their feelings of sorrow and regret. Mr. Kusuki’s whereabouts after he was photographed are unclear. His remains have yet to be found.

What happened to people under the A-bomb’s enormous mushroom cloud? Taking advantage of Nihon Hidankyo’s being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, people in the world need to confront that question. In remarks he made at the award ceremony, Jørgen Watne Frydnes, chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, made an appeal. “The Nobel Peace Prize for 2024 validates the most fundamental human right, the right to live,” said Mr. Frydnes.

A single bomb destroyed the city instantly. It burned human bodies so severely they were unidentifiable even by family. The A-bombing’s radiation ate away at the survivors’ bodies and persisted in taking their lives. Abandoned by the national government for years, those who survived faced discrimination and bias.

In the shadow of the “nuclear age” of world history, an era marked by nuclear competition among major powers such as the United States, the nation that continued to justify the atomic bombings, and by other nations’ tireless efforts to get their own hands on nuclear weapons, many people were deprived of their “right to live.” In his remarks, Mr. Frydnes referred to that reality, emphasizing the significance of seeing things from the point of view of the survivors. “Their personal stories humanize history,” he said.

That remark echoes the calls made by those who came before and have died. Heiichi Fujii, the first secretary-general of Nihon Hidankyo, once said, “We want to make the history of everyday people the history of the world.”

To turn the “documents” showing the horrors of the atomic bombing into a heritage of all of humanity, the “Documenting Hiroshima” series traced a variety of materials and collected testimonies of experiences in the atomic bombing in an attempt to convey to the world the history of Hiroshima’s citizens after the atomic bombing. The articles cover not only the human misery engendered by nuclear weapons and war but also the actions of citizens, which offer clues for bridging the deepening divide we now all face. Those actions included the initial anti-nuclear movement, which achieved solidarity among different political factions and gave rise in isolated survivors the feeling, “I’m glad to be alive,” as well as support for “hibakusha (A-bomb survivors)” living overseas and those suffering from nuclear testing.

In pursuit of that starting point, one of articles in the “Documenting Hiroshima” series covered the story of the journal Ichiro Moritaki had written the year after the atomic bombing. In his journal entry dated May 29, 1946, Mr. Moritaki was wrote, “World history must make a major shift from a history of power to a history of love. Otherwise, humanity will not be saved.” That was undoubtedly a cry from his soul.

Will we continue to intimidate each other with force, walking a path that skirts ruin? Or will we overcome our differences and pursue together a world in which no one is deprived of “the right to live”? Past history as conveyed in the “Documenting Hiroshima” series sets up as a test of our actions for the future.

Chugoku Shimbun introduces all article series on special website: Symposium scheduled to be held in Hiroshima on July 19

The Chugoku Shimbun has launched a special website titled “Documenting Hiroshima.” In the “1945” section, article headlines are listed by date of publication. When a headline is clicked, the body of the article appears. In the “1946” and “80 years after A-bombing” sections, articles are sorted and listed by month and decade. In the “Witnesses to horrors of atomic bombing” section, stories about the lives of six people can be read in one sitting. For the time being, the articles in the four series are available for everyone to read free of charge.

In addition, starting at 1:30 p.m. on July 19, the Chugoku Shimbun, the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, and the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition/Nagasaki University (RECNA) will jointly hold a symposium titled “International Symposium 2025 Memories for the Future: How to Pass Down A-bomb Archives as a Living Testament,” at the International Conference Center Hiroshima in the city’s Naka Ward. The symposium will include a keynote speech by a non-profit organization engaged in the collection and preservation of materials related to the A-bomb survivors’ movement, and reports from the staff writers in charge of the different series of articles. Advance registration is not required, but admission will be limited to the first 450 people to arrive. Admission is free.

(Originally published on June 29, 2025)