Photo anthology “Living Hiroshima” depicts city’s devastation and recovery

Dec. 19, 2010

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

An anthology of photographs, “Living Hiroshima,” was published in 1949 under the Allied Occupation despite the U.S. military’s censorship of publications related to the atomic bombing. How was the publication put together? What was its impact? For this article the Chugoku Shimbun sought out people who were involved in the project and materials that were used in its publication. We uncovered the full story behind this forgotten collection of photographs that was the first to depict the devastation of the atomic bombing as well as the overlooked issues it raised.

Originally, the prefectural tourism association planned to issue a publication under the title “Graphic Hiroshima.” A circular stating that it was to be put together by a publisher called Setonaikai Bunko (Seto Inland Sea Library) can be found in the Hiroshima City Central Library’s collection of materials related to Sankichi Toge. Mr. Toge, who worked for the publishing company, later became famous for his book “A-bomb Poetry.”

The circular stated that the photo anthology would combine images of the atomic bombing and Hiroshima Prefecture’s Setonaikai National Park and introduce them to the countries of the world. “Tokyo’s Bunka-sha, currently regarded as the top company of its kind in Japan, has been selected to do the production,” the circular noted. “Kenzo Nakajima has been asked to do the writing, while Ihei Kimura and other top photographers have been asked to provide photographs.”

Bunka-sha was founded in November 1945, three months after the end of the war, by Mr. Nakajima, who was executive director of Toho-sha, which published the propaganda magazine “Front” for foreign readers during World War II, and Kimura, who was head of Toho-sha’s photography department. In April 1946 Bunka-sha published a photo anthology entitled “Tokyo: Autumn, 1945.”

Setonaikai Bunko brought critics, photographers and others who had been well known since before the war to Hiroshima and set up a publishing division in the spring of 1946 in the downtown area of the city. The effort began with the sale of books. Tsuguzo Tanaka, founder of the company, had served as executive director of the booksellers’ association during the war.

“My dad had a lot of good ideas, but he never thought about money, so my mother had a tough time,” recalled Eiko Kaneko, 82, Mr. Tanaka’s daughter. Her cousin Setsuyo Tanaka, 87, worked in the bookstore division of the company. “It was difficult to entertain important people from Tokyo in those days when there was a shortage of food,” she said.

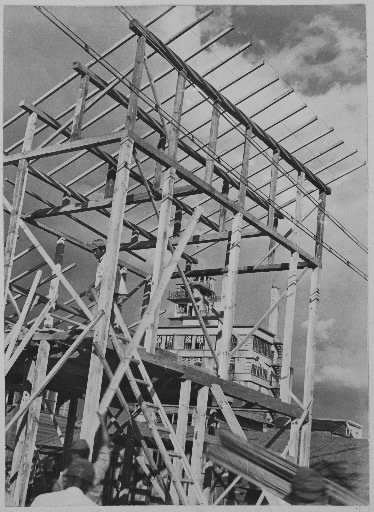

The September 21, 1947 edition of “Hiroshima,” the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, reported that Bunka-sha photographers had begun taking pictures. Shunkichi Kikuchi and Minoru Oki, who had both worked on “Front,” began photographing in the city center on August 25 and later traveled to other areas including Kure, Onomichi and Tomo no Ura. (Mr. Kikuchi died in 1990 at the age of 74.) In an interview Mr. Kimura told a reporter, “The city has recovered much more than I expected. I was really surprised.” He began taking photographs on September 18.

The first Peace Festival (now the Peace Memorial Ceremony) was held that summer. The population of the city had grown from about 136,000 just after the atomic bombing to 224,000, and the people of Hiroshima had a sense of peace as they sought the rebirth of their city.

According to Kikuchi’s records, photographs were taken through October 17. But publication of “Living Hiroshima” was delayed significantly, blocked by censorship undertaken amid an ongoing conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. In “Graphic Hiroshima Report,” which was published in May 1948, Mr. Tanaka left a remark that indicated this circumstance.

He apologized for the delay, writing, “If this photographic magazine is taken to other countries, it may be used for negative publicity.” Kaneko recalled her father saying that he was determined that the images in the publication not be overly distressing.

In the 1979 “Kaiso no Sengo Bungaku” (“Retrospective Postwar Literature”), Mr. Nakajima, who had been the editor of “Living Hiroshima,” recalled those days. “There were tight restrictions on articles about the destruction in Hiroshima…It was a task fraught with difficulty,” he wrote.

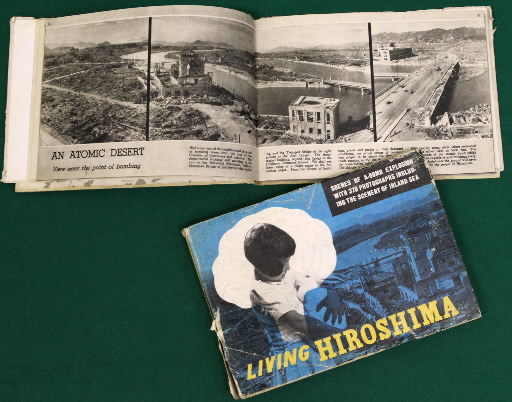

The 128-page “Living Hiroshima” was published in May 1949 entirely in English. It featured 378 photographs.

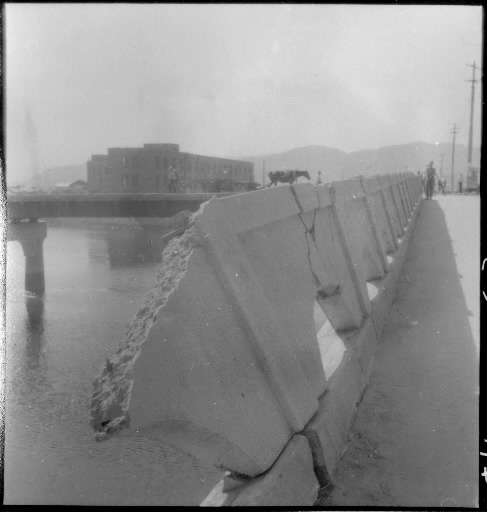

A close examination of the photos revealed that 49 of them were taken by Mr. Kimura. It was also confirmed that 62 of the photos were taken in October 1945 by Mr. Kikuchi and Shigeo Hayashi, both former employees of Toho-sha who traveled with a documentary film team from the former Education Ministry’s Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage. (Mr. Hayashi died in 2002 at the age of 84.) The photo anthology breathed new life into the effort to rebuild the city and provided one of the first looks at the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

Records show that the initial print run was 5,000 copies and that a second printing of 10,000 copies was undertaken six months later. Mr. Kaneko and others recalled that the prefecture and other groups gave the books away as gifts to the occupation army and other foreigners and that they were not sold in stores. Setonaikai Bunko was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1950 as the result of rapid inflation and rising costs, and the photo anthology was subsequently forgotten.

Satoru Ubuki, a professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University, is well versed in the history of the atomic bombing. “Starting in the occupation several serious attempts were made to provide a true picture of the devastation caused by the atomic bomb, but members of the peace movement spoke out and dismissed those attempts as adhering to U.S. policy,” he said. “It would be good if more cultural activities during the occupation could be brought to light and reviewed.”

In order to repay debts, Mr. Tanaka worked in Osaka and Tokyo and donated the materials connected to the photo anthology, including the anthology itself, as well as those regarding Setonaikai Bunko to the prefectural library in 1979, just after returning to his hometown of Hiroshima. Fortunately, the materials were well preserved in the cardboard boxes in which they had been stored. Four years ago the materials, apart from the contact prints used in the anthology, were transferred to the prefectural archives. The photo anthology “Living Hiroshima,” which was lauded by Mr. Ubuki as “heralding the internationalization of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima,” can be viewed there, along with related materials.

(Ihei Kimura’s prints and contact prints were provided courtesy of the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives and the Hiroshima Prefectural Library, where they are stored, respectively, with the permission of Mr. Kimura’s copyright holder.)

(Originally published Dec. 12, 2010)

Related articles

Vivid photos taken two years after atomic bombing (Dec. 12, 2010)

An anthology of photographs, “Living Hiroshima,” was published in 1949 under the Allied Occupation despite the U.S. military’s censorship of publications related to the atomic bombing. How was the publication put together? What was its impact? For this article the Chugoku Shimbun sought out people who were involved in the project and materials that were used in its publication. We uncovered the full story behind this forgotten collection of photographs that was the first to depict the devastation of the atomic bombing as well as the overlooked issues it raised.

Originally, the prefectural tourism association planned to issue a publication under the title “Graphic Hiroshima.” A circular stating that it was to be put together by a publisher called Setonaikai Bunko (Seto Inland Sea Library) can be found in the Hiroshima City Central Library’s collection of materials related to Sankichi Toge. Mr. Toge, who worked for the publishing company, later became famous for his book “A-bomb Poetry.”

The circular stated that the photo anthology would combine images of the atomic bombing and Hiroshima Prefecture’s Setonaikai National Park and introduce them to the countries of the world. “Tokyo’s Bunka-sha, currently regarded as the top company of its kind in Japan, has been selected to do the production,” the circular noted. “Kenzo Nakajima has been asked to do the writing, while Ihei Kimura and other top photographers have been asked to provide photographs.”

Bunka-sha was founded in November 1945, three months after the end of the war, by Mr. Nakajima, who was executive director of Toho-sha, which published the propaganda magazine “Front” for foreign readers during World War II, and Kimura, who was head of Toho-sha’s photography department. In April 1946 Bunka-sha published a photo anthology entitled “Tokyo: Autumn, 1945.”

Setonaikai Bunko brought critics, photographers and others who had been well known since before the war to Hiroshima and set up a publishing division in the spring of 1946 in the downtown area of the city. The effort began with the sale of books. Tsuguzo Tanaka, founder of the company, had served as executive director of the booksellers’ association during the war.

“My dad had a lot of good ideas, but he never thought about money, so my mother had a tough time,” recalled Eiko Kaneko, 82, Mr. Tanaka’s daughter. Her cousin Setsuyo Tanaka, 87, worked in the bookstore division of the company. “It was difficult to entertain important people from Tokyo in those days when there was a shortage of food,” she said.

The September 21, 1947 edition of “Hiroshima,” the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, reported that Bunka-sha photographers had begun taking pictures. Shunkichi Kikuchi and Minoru Oki, who had both worked on “Front,” began photographing in the city center on August 25 and later traveled to other areas including Kure, Onomichi and Tomo no Ura. (Mr. Kikuchi died in 1990 at the age of 74.) In an interview Mr. Kimura told a reporter, “The city has recovered much more than I expected. I was really surprised.” He began taking photographs on September 18.

The first Peace Festival (now the Peace Memorial Ceremony) was held that summer. The population of the city had grown from about 136,000 just after the atomic bombing to 224,000, and the people of Hiroshima had a sense of peace as they sought the rebirth of their city.

According to Kikuchi’s records, photographs were taken through October 17. But publication of “Living Hiroshima” was delayed significantly, blocked by censorship undertaken amid an ongoing conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. In “Graphic Hiroshima Report,” which was published in May 1948, Mr. Tanaka left a remark that indicated this circumstance.

He apologized for the delay, writing, “If this photographic magazine is taken to other countries, it may be used for negative publicity.” Kaneko recalled her father saying that he was determined that the images in the publication not be overly distressing.

In the 1979 “Kaiso no Sengo Bungaku” (“Retrospective Postwar Literature”), Mr. Nakajima, who had been the editor of “Living Hiroshima,” recalled those days. “There were tight restrictions on articles about the destruction in Hiroshima…It was a task fraught with difficulty,” he wrote.

The 128-page “Living Hiroshima” was published in May 1949 entirely in English. It featured 378 photographs.

A close examination of the photos revealed that 49 of them were taken by Mr. Kimura. It was also confirmed that 62 of the photos were taken in October 1945 by Mr. Kikuchi and Shigeo Hayashi, both former employees of Toho-sha who traveled with a documentary film team from the former Education Ministry’s Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage. (Mr. Hayashi died in 2002 at the age of 84.) The photo anthology breathed new life into the effort to rebuild the city and provided one of the first looks at the devastation caused by the atomic bombing.

Records show that the initial print run was 5,000 copies and that a second printing of 10,000 copies was undertaken six months later. Mr. Kaneko and others recalled that the prefecture and other groups gave the books away as gifts to the occupation army and other foreigners and that they were not sold in stores. Setonaikai Bunko was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1950 as the result of rapid inflation and rising costs, and the photo anthology was subsequently forgotten.

Satoru Ubuki, a professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University, is well versed in the history of the atomic bombing. “Starting in the occupation several serious attempts were made to provide a true picture of the devastation caused by the atomic bomb, but members of the peace movement spoke out and dismissed those attempts as adhering to U.S. policy,” he said. “It would be good if more cultural activities during the occupation could be brought to light and reviewed.”

In order to repay debts, Mr. Tanaka worked in Osaka and Tokyo and donated the materials connected to the photo anthology, including the anthology itself, as well as those regarding Setonaikai Bunko to the prefectural library in 1979, just after returning to his hometown of Hiroshima. Fortunately, the materials were well preserved in the cardboard boxes in which they had been stored. Four years ago the materials, apart from the contact prints used in the anthology, were transferred to the prefectural archives. The photo anthology “Living Hiroshima,” which was lauded by Mr. Ubuki as “heralding the internationalization of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima,” can be viewed there, along with related materials.

(Ihei Kimura’s prints and contact prints were provided courtesy of the Hiroshima Prefectural Archives and the Hiroshima Prefectural Library, where they are stored, respectively, with the permission of Mr. Kimura’s copyright holder.)

(Originally published Dec. 12, 2010)

Related articles

Vivid photos taken two years after atomic bombing (Dec. 12, 2010)