Sarashina, A-bomb survivor in U.S., “meets” wife’s memoir for first time with tears at Memorial Hall while visiting Hiroshima with family

Aug. 25, 2025

by Yumi Kanazaki and Natsumi Hiyama, Staff Writers

This month, on the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Junji Sarashina, a 96-year-old atomic bomb survivor living in California, the United States, temporarily returned to Japan with thoughts of consoling the spirits of his wife, Kiyoko, an atomic bomb survivor who passed away the year before last at the age of 92, and other victims, in his heart. At the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, he “met for the first time” Kiyoko’s personal account of the atomic bombing, which she would not talk about while she was alive. Mr. Sarashina’s son and grandchild, who accompanied him, felt the feelings she kept to herself.

The City of Hiroshima invited Mr. Sarashina, president of the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-bomb Survivors (ASA), to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony. On August 6, he attended the ceremony with his 64-year-old son, James, and his 22-year-old granddaughter, Emily. He submitted an application to Hiroshima City Hall window to have Kiyoko’s name added to the register of atomic bomb victims, and another to Memorial Hall to register her photograph at the facility.

When he visited Memorial Hall for registration, the staff informed him they house Kiyoko’s personal account of the atomic bombing, which she had sent to the city in response to its call in 1997, before the Hall opened.

According to her memoir, Kiyoko was a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (now Minami High School) and experienced the atomic bombing in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), where she had been mobilized for the war effort. She was covered in blood from her injuries, saw “a throng of grotesque people” walking with their arms stretched out in front of them, was exposed to “black rain,” and carried the wounded on a stretcher. She “wrote it down for the repose of the souls of the victims who died a regrettable death, whether or not they were related by blood, thinking it was the responsibility of the survivors.”

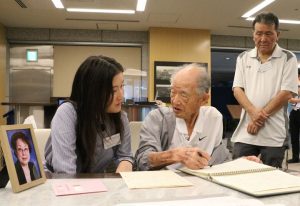

After silently reading her account of a 10-page manuscript paper written in neat handwriting, Mr. Sarashina said, dabbing at his eyes: “She showed absolutely no signs of writing it. It is as if she is sitting beside me, speaking.” When he read it out to James and Emily in English, they said they did not know of any of the things in her account and wiped away their tears.

Mr. Sarashina was born into a family of a monk who had emigrated to Hawaii from what is now the city of Akitakata. He later came to Hiroshima, where he attended Hiroshima First Middle School (now Kokutaiji High School). He experienced the atomic bombing at an arsenal in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). His family was temporarily broken up as his father was sent to an internment camp on the U.S. mainland. Even after returning to the United States, Mr. Sarashina was mobilized for the Korean War as an American soldier, living a life cheek by jowl with war. He has shared his experience of the bombing in the country that used the atomic bomb, describing the horrible sights he witnessed at his school and his regret for not being able to save the underclass students. He also talks about his wish for a peaceful world without nuclear weapons.

At the end of his trip to Hiroshima, he returned to Memorial Hall to see Kiyoko’s portrait, now available on a touch screen. He also agreed to open her personal account to the public. “Now, I can see my wife at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, where the register of the victims is placed, and the Memorial Hall, where her photograph and personal account are housed,” said Mr. Sarashina. Saying she feels close to Hiroshima and the atomic bomb experience of her grandparents, Emily placed her hands together in prayer before the touch screen.

Keywords

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

Opened in August 2002. The facility includes the Hall of Remembrance, where people can mourn for the victims of the atomic bombing, an information area with the names and memorial photographs of the victims, and a library, where visitors can read survivors’ personal accounts. In principle, memorial photographs can be registered upon application from bereaved family members. The Memorial Hall also accepts name-only registrations. It currently has about 29,000 registered names and photographs, as well as more than 150,000 personal accounts of experiences with the atomic bomb.

(Originally published on August 25, 2025)

This month, on the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Junji Sarashina, a 96-year-old atomic bomb survivor living in California, the United States, temporarily returned to Japan with thoughts of consoling the spirits of his wife, Kiyoko, an atomic bomb survivor who passed away the year before last at the age of 92, and other victims, in his heart. At the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, he “met for the first time” Kiyoko’s personal account of the atomic bombing, which she would not talk about while she was alive. Mr. Sarashina’s son and grandchild, who accompanied him, felt the feelings she kept to herself.

The City of Hiroshima invited Mr. Sarashina, president of the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-bomb Survivors (ASA), to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony. On August 6, he attended the ceremony with his 64-year-old son, James, and his 22-year-old granddaughter, Emily. He submitted an application to Hiroshima City Hall window to have Kiyoko’s name added to the register of atomic bomb victims, and another to Memorial Hall to register her photograph at the facility.

When he visited Memorial Hall for registration, the staff informed him they house Kiyoko’s personal account of the atomic bombing, which she had sent to the city in response to its call in 1997, before the Hall opened.

According to her memoir, Kiyoko was a third-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School (now Minami High School) and experienced the atomic bombing in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), where she had been mobilized for the war effort. She was covered in blood from her injuries, saw “a throng of grotesque people” walking with their arms stretched out in front of them, was exposed to “black rain,” and carried the wounded on a stretcher. She “wrote it down for the repose of the souls of the victims who died a regrettable death, whether or not they were related by blood, thinking it was the responsibility of the survivors.”

After silently reading her account of a 10-page manuscript paper written in neat handwriting, Mr. Sarashina said, dabbing at his eyes: “She showed absolutely no signs of writing it. It is as if she is sitting beside me, speaking.” When he read it out to James and Emily in English, they said they did not know of any of the things in her account and wiped away their tears.

Mr. Sarashina was born into a family of a monk who had emigrated to Hawaii from what is now the city of Akitakata. He later came to Hiroshima, where he attended Hiroshima First Middle School (now Kokutaiji High School). He experienced the atomic bombing at an arsenal in Minamikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). His family was temporarily broken up as his father was sent to an internment camp on the U.S. mainland. Even after returning to the United States, Mr. Sarashina was mobilized for the Korean War as an American soldier, living a life cheek by jowl with war. He has shared his experience of the bombing in the country that used the atomic bomb, describing the horrible sights he witnessed at his school and his regret for not being able to save the underclass students. He also talks about his wish for a peaceful world without nuclear weapons.

At the end of his trip to Hiroshima, he returned to Memorial Hall to see Kiyoko’s portrait, now available on a touch screen. He also agreed to open her personal account to the public. “Now, I can see my wife at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, where the register of the victims is placed, and the Memorial Hall, where her photograph and personal account are housed,” said Mr. Sarashina. Saying she feels close to Hiroshima and the atomic bomb experience of her grandparents, Emily placed her hands together in prayer before the touch screen.

Keywords

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

Opened in August 2002. The facility includes the Hall of Remembrance, where people can mourn for the victims of the atomic bombing, an information area with the names and memorial photographs of the victims, and a library, where visitors can read survivors’ personal accounts. In principle, memorial photographs can be registered upon application from bereaved family members. The Memorial Hall also accepts name-only registrations. It currently has about 29,000 registered names and photographs, as well as more than 150,000 personal accounts of experiences with the atomic bomb.

(Originally published on August 25, 2025)